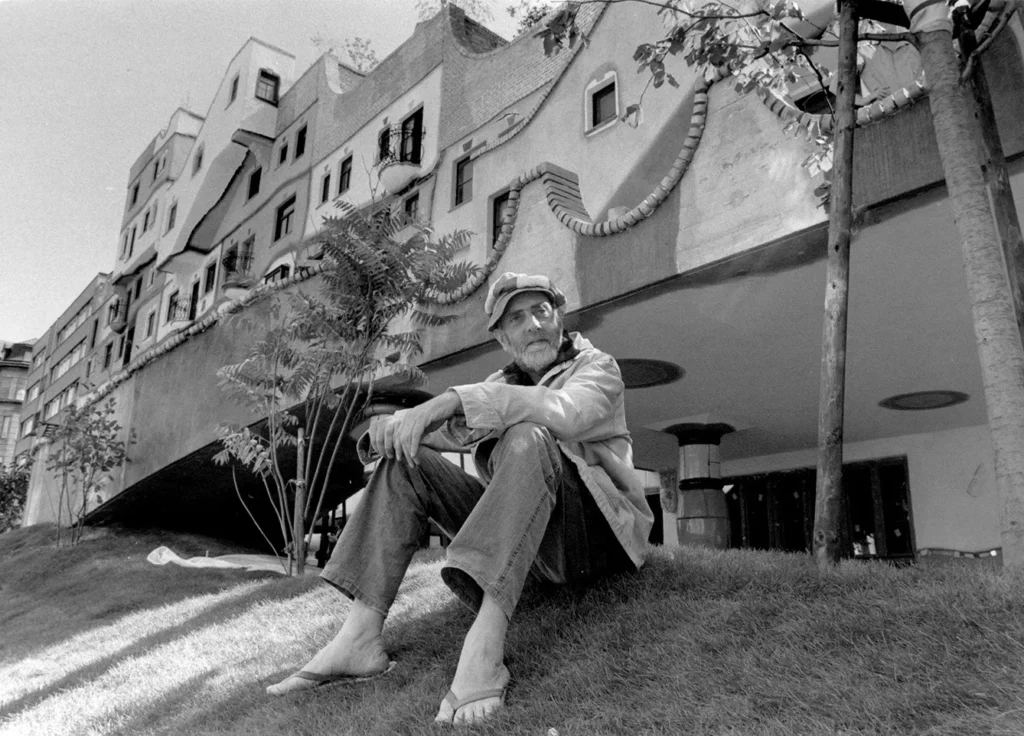

One of many anecdotes and factoids about Friedensreich Hundertwasser was how he designed his buildings. He would create a mockup and seemingly randomly mark its features, such as windows or balconies, on its walls. And thus, creating a problem for architects, you know, those guys and gals actually building stuff, to get things done.

Looking at his eponymous Hundertwasser House, it’s easy to believe the story. Located on the Danube Canal, just opposite the world’s oldest amusement park Präter, it’s a strong accent of the district known as Weissgerberviertel. And from one side, it looks like a district – a checkerboard of assorted elevations peppered with windows, balconies, and loggias, none matching any other, crooked pillars and colors as if the aged building was stained from centuries of use.

Hundertwasser’s dialogue with nature

Yet, it is a building from 1986, perhaps one of the best-known gems of postmodern architecture (*if you subscribe to the idea that postmodern architecture produced any, that is.) The dialogue with nature is the idea behind the fluidity of form, escape from grid design and an unexpected assemblage of stylistically different elements.

Full-sized trees grow here even on the roof, balconies host a mass of green plants, and seen from a little distance, the building can seem like scraps of broken houses thrown around the bush. The Hundertwasser House, the first in a series (others were built in the German cities of Plochingen, Darmstadt, and Magdeburg), is not a museum, though.

Yes, people do actually live there (hello, lucky!). Fifty flats, sized from single-person to penthouses, are mostly inhabited (you can try Airbnb). But if you can’t actually live in the house, try visiting a restaurant or souvenir shop with Friedrensreich Hundertwasser art on the ground floor (and take a look around). The last time I was there (staying in a flat with a view of beehives hidden among the roof trees), I bought myself a zero-euro banknote (for four euros). This brilliant Hundertwasser pun may be a great testimony to the late artist’s uniqueness.

Post stamps and abstract buildings

Born as Friedrich Stowasser in 1928 and soon orphaned by his father, he was a Jew, yet christened and – when Nazi Germany annexed Austria, he joined the Hitlerjugend. He studied art in Vienna – but only for three months. On the brink of his artist career, he assumed the last name Hundertwasser (Hundred-water) and explained that what fascinates him about water is its unpredictability and flow.

Being a postmodern artist, he is considered an heir to the Viennese Secession movement, famous for its art nouveau style. He always advocated for integration between man and nature, and one of his works is the proposal of the new flag for New Zealand, reflecting this integration.

Hundertwasser died on the cruise ship – Queen Elizabeth II – in 2000. He was buried at his estate in New Zealand, naked and wrapped in his proposed flag, without a coffin. This flag is just one of the unusual ways he expressed himself as an artist. While one of them is architecture, in which he had no training, he was also famous for designing postage stamps.

That is perhaps because Friedensreich Hundertwasser, as an artist, was mostly a follower of his own mind and ideas and not of a particular school of thought. And Vienna’s Hundertwasserhaus is a great symbol of that uniqueness.