The most piece of men’s jewelry is the watch, the best watchmakers are in Switzerland, and the best of all of them is Patek Philippe. Obviously, that’s not a hard fact, as there is no such thing as paramount quality. Instead, it’s a collective sentiment that Swiss watches, some of them reaching prices over EUR 300,000 (add to that EUR 10 for packaging and postage), are simply the best.

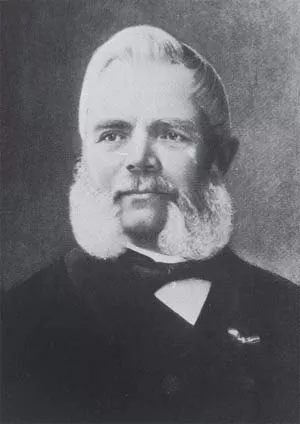

Antoni Patek: Polish watchmaking icon

And if you think that Patek is a strange name for mostly German-speaking Switzerland, you’re right. Antoni Patek grew up in Poland before he made his career in the watchmaking industry. And his grave in Geneva still carries Polish flags to commemorate the fact. Patek’s creativity and business skill granted him an important role in this jewelry-adjacent industry.

To add to that, the location of Patek’s birthplace is not even the western part of Poland. Yes, Lublin, now perhaps its easternmost large city, was more central to then-Polish territory and far from Poland’s window to the world. But then again, Patek was not an economical emigrant but a political one. (*Later, after he gained his wealth, he would support this Polish movement abroad.)

Born in 1812, during the brief Napoleon-dependent (but therefore free from Russian imperial reign) Księstwo Warszawskie, Antoni Patek grew up in Piaski Szlacheckie near Lublin, soon reclaimed by Russia from defeated Napoleon.

As a teenager, he joined the army. Poland was still somewhat autonomous, with a union with Russia forced upon it. So, technically, he was more a Polish than a Russian soldier. But in 1830, the first of a series of Polish uprisings (the November Uprising) broke out, and Patek went to fight against his King, the Tzar.

The Great Emigration

Having failed miserably in winning the irregular warfare against the Empire, the November Uprising sent Antoni Patek, along with thousands and thousands of his fellow soldiers, abroad as emigrants. This first wave of what Polish history calls the Great Emigration led them mostly to France, which is precisely where Antoni Patek landed.

Forced to become a citizen rather than an aristocrat, he tried a few occupations, at one point even working as a typesetter. When the French-Russian agreement ruled out the settlement of Polish émigrés, Patek was forced to move abroad, and this is how he found himself in Switzerland. He took up painting and got into the wine trade, but when he came upon watchmaking, he knew that this was his true calling.

But there was a problem: a typesetter’s experience was not enough to become a watchmaker, a multifold, more sophisticated trade. So Patek took another route to his watch brand: watch case adornment. His first successes were among other Polish emigrants who were looking for patriotic souvenirs.

Patek, Czapek, and Philippe

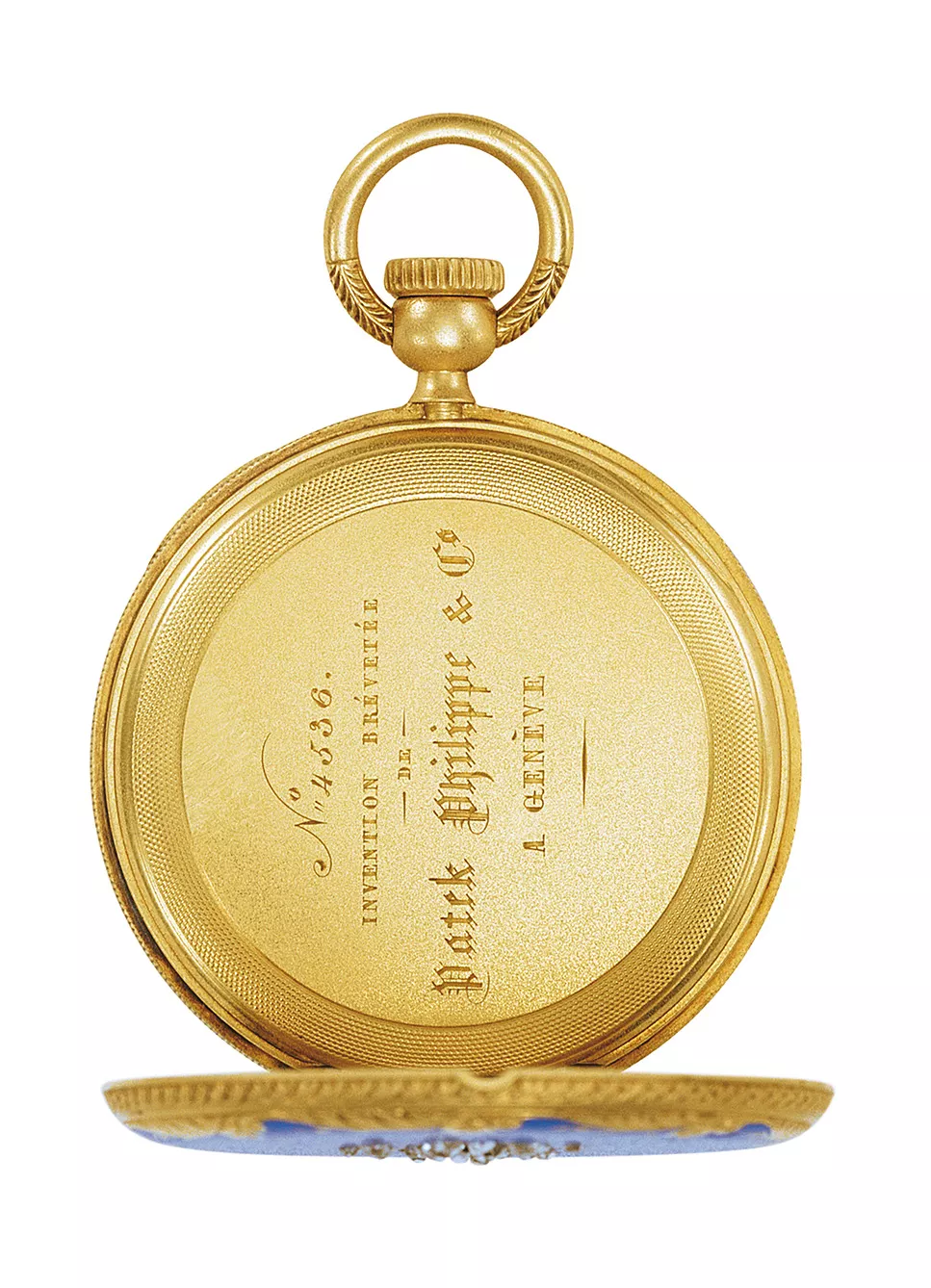

His career really took off when he found an associate: Patek got into partnership with Franciszek Czapek, a Pole with Czech roots. They established a watchmaking manufacturer. Later, Czapek left the company, opening the door for Adrien Philippe to join it. Philippe was the creator of the new watchmaking patent: the watch crown, which allowed watch users to get rid of the winding key.

Philippe’s input into business was obvious, but Patek had his equal share. He turned out to be a very skilled businessman. He traveled extensively (even to Russia) to find customers for their precious produce. This led to fame, and fame got them to the famous 1851 World Exhibition in London.

Queen Victoria was the first royalty to buy a Patek-Philippe watch. As such, it remains king among watches, though the watchmaker made watches not only for royalty. Watchmaking changed after the crown-winded watch appeared, and Patek was largely a contributor to the phenomenon of the modern relationship between man and his watch.