When Polish modernist artist Tadeusz Kantor claimed that “Every revolution begins at a café,” he might have coined a metaphor, but he was not far from the truth. The 19th-century coffee house movement, along with the invention of modern newspapers, which were read and discussed there, was one of the most essential factors in creating modern society.

Coffee in Europe: hot brew

And, to some extent, the brew itself can claim some credit – a reviving, invigorating, and bitter drink that leaves you revived, invigorated, and, well, sometimes bitter. But that takes us back to the root of all that jazz, to the time when coffee and cafés were the revolutions themselves.

Known widely in the Middle East and not alien to Islamic countries, caffeinated drinks were present in Turkey, which fought and conquered parts of Central Europe over centuries. As such, coffee was already present in Turkey-controlled Hungary and was even introduced in Vienna after the Siege of 1529. Only a century and a half later, it fought a decisive battle for popularity in Europe.

Historians call it the Battle of Vienna of 1683, but it also holds a special place in Polish history. That’s because the then-Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was an essential ally of the Habsburg-ruled Holy Empire and was responsible for the Relief of Vienna (Odsiecz Wiedeńska) – one of history’s epic battles.

During this siege of Vienna by the Ottoman forces, Central Europe’s magnificent central city was cut away from any supplies and on the edge of starvation when the Polish army under King Jan III Sobieski (now, famously, the patron of a Polish vodka brand) brought the Austrian citizens an eponymous relief after a one-day battle of 12 August 1683.

The battle was an overwhelming success, both tactically and strategically, undermining the Ottoman power for centuries to come. King Sobieski famously paraphrased Julius Caesar by saying: Veni, Vidi, Deus vicit – we came, we saw, God prevailed.

Legends aside… or not

The Vienna Relief gave birth to many legends. One of them tells the story of how coffee was introduced in Vienna. There are a few existing versions of the legend. The most elaborate one narrates the story of sacks of strange-looking grains discovered in the abandoned Turkish camp. Soldiers of the allied forces supposedly didn’t know what to do with them. They thought perhaps they were filled with horse fodder, as they didn’t know any better.

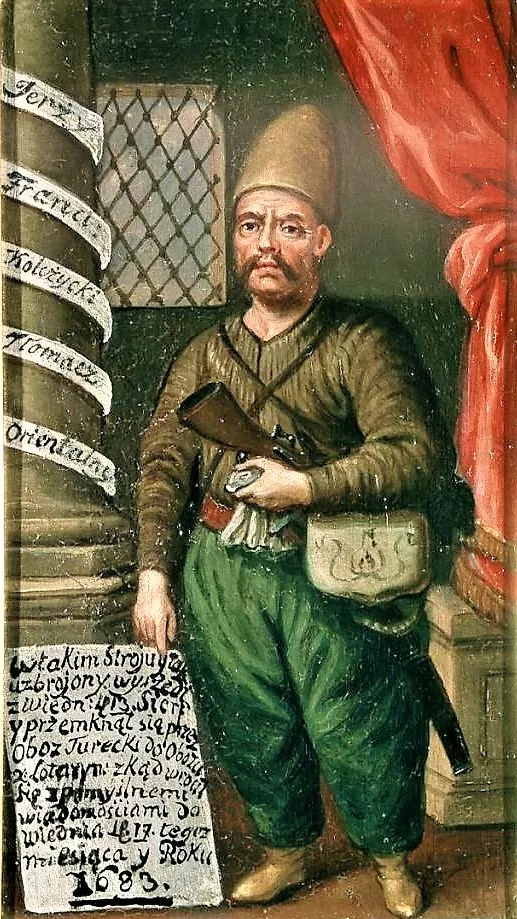

Then, a Polish soldier, a spy, and a diplomat – Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki – a former translator for the Austria Oriental Company in Belgrade knew the Turkish culture well enough to take the grain for the grain it was: coffee beans. He relieved his allies of the duty of handling this peculiar “horse fodder” and took the “useless” beans back to his home in Vienna.

The legend has it that this was the origin of the first Viennese coffee house that opened soon after the siege. It was called The Blue Bottle Inn (Hof zur Blauen Flasche) and was located on Schlossergassl Street. The story taken for a fact for centuries is now disputed. In the light of new evidence, it is possible that the first café in the city was opened in 1685 by a tradesman named Johannes Theodat of Armenia.

Regardless of details, one thing is indisputable: Vienna remains the heartland of the European café movement, though France soon joined in. Kulczycki remains the campaign’s patron, with a statue and a street of his name in Vienna (with German spelling: Kolschitzky). And the Viennese coffee house culture, with its décor of Thonet chairs and dark panels, where coffee is served with a generous dollop of milk, remains a vital part of the Viennese lifestyle.

The Austrian Intangible Cultural Heritage list says it all: Viennese coffee houses are places “where time and space are consumed, but only the coffee is found on the bill.”