What’s more, his legacy lives on in Africa to this day. He compiled the most detailed ethnographic writings of African tribes that exist. The tribes of modern-day Zambia and Zimbabwe, in particular, still learn about their history, origins, and culture from this Czech explorer’s texts and reports. Who was he?

Exploring doctor

Emil Holub was born in 1847 to a prominent medical family. Young Emil followed in his father’s footsteps and became a doctor. Throughout his childhood and youth, he read the travelogues of Kryštof Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice. He was also fond of the texts by the British explorer David Livingstone. Both men strongly influenced him: Harant sparked his love for traveling and exploring, while Livingston sparked his deep love of Africa.

During his studies, Holub met Vojtěch Náprstek, an important Czech traveler and diplomat. Náprstek, who fled to the United States after the failed Czech Revolution of 1848, devoted himself to studying Native American tribes on the new continent. And it was Náprstek who deepened Holub’s love of travel, exploration, and, most profoundly, ethnography.

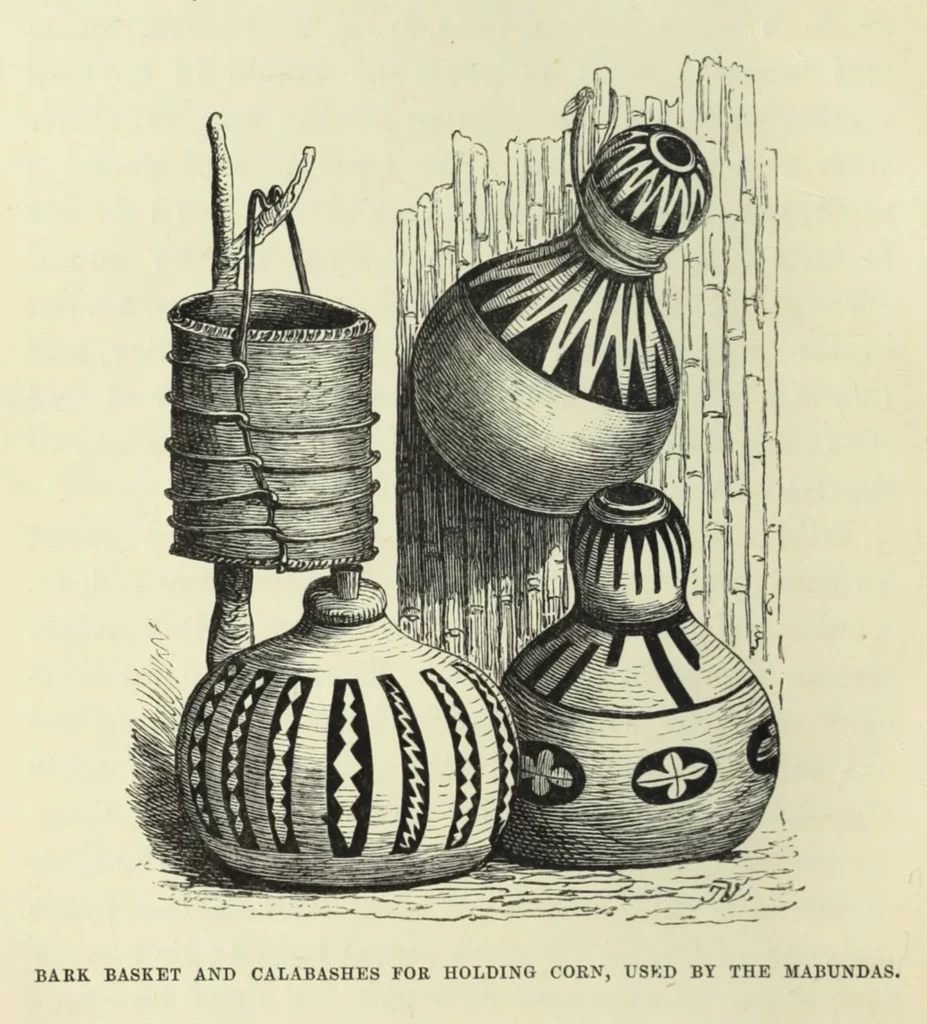

“Mask of a kishi-dancer”, “Bark basket and calabashes for holding corn, used by the Mabundas”. Photos: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

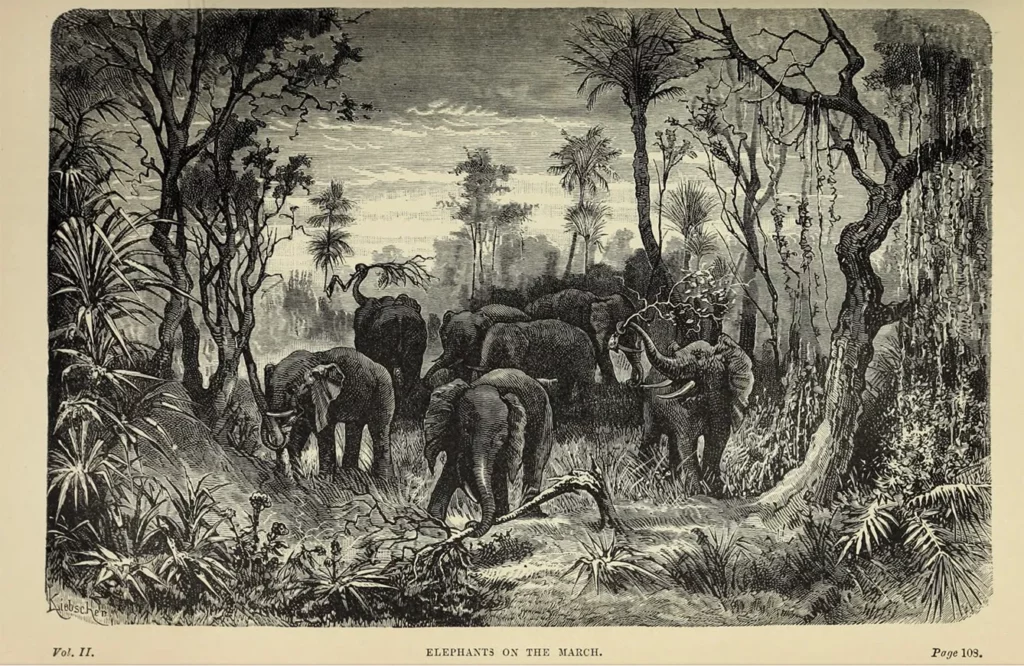

And so, in May 1872, Holub sailed to Africa to work as a doctor among the European colonists. Despite being a successful and popular doctor, his life was still not fulfilled. Even being in his beloved Africa, Holub dreamed of something more. He dreamed of discovering new tribes, making his way through dense jungles, and climbing high mountains.

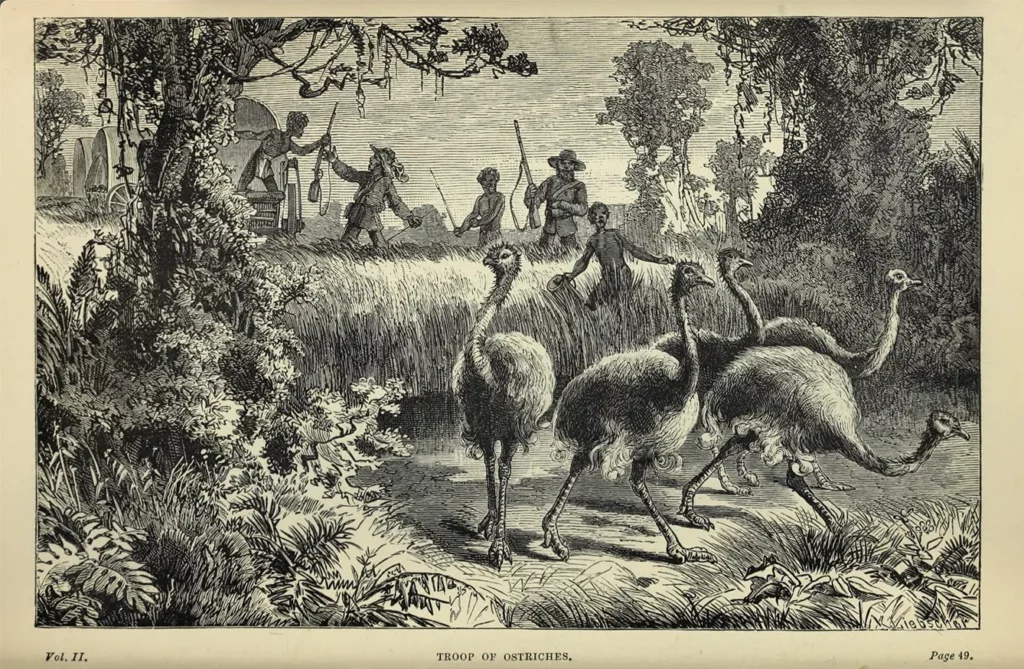

His wish was granted, and his fate was sealed a year later, in 1873, when he set off on a two-month “scientific safari” among the local tribes. It was clear that he would never return to his medical profession. On this first scientific journey, he gained experience with the natives and the explorers’ gear.

Baptism by the African Sun

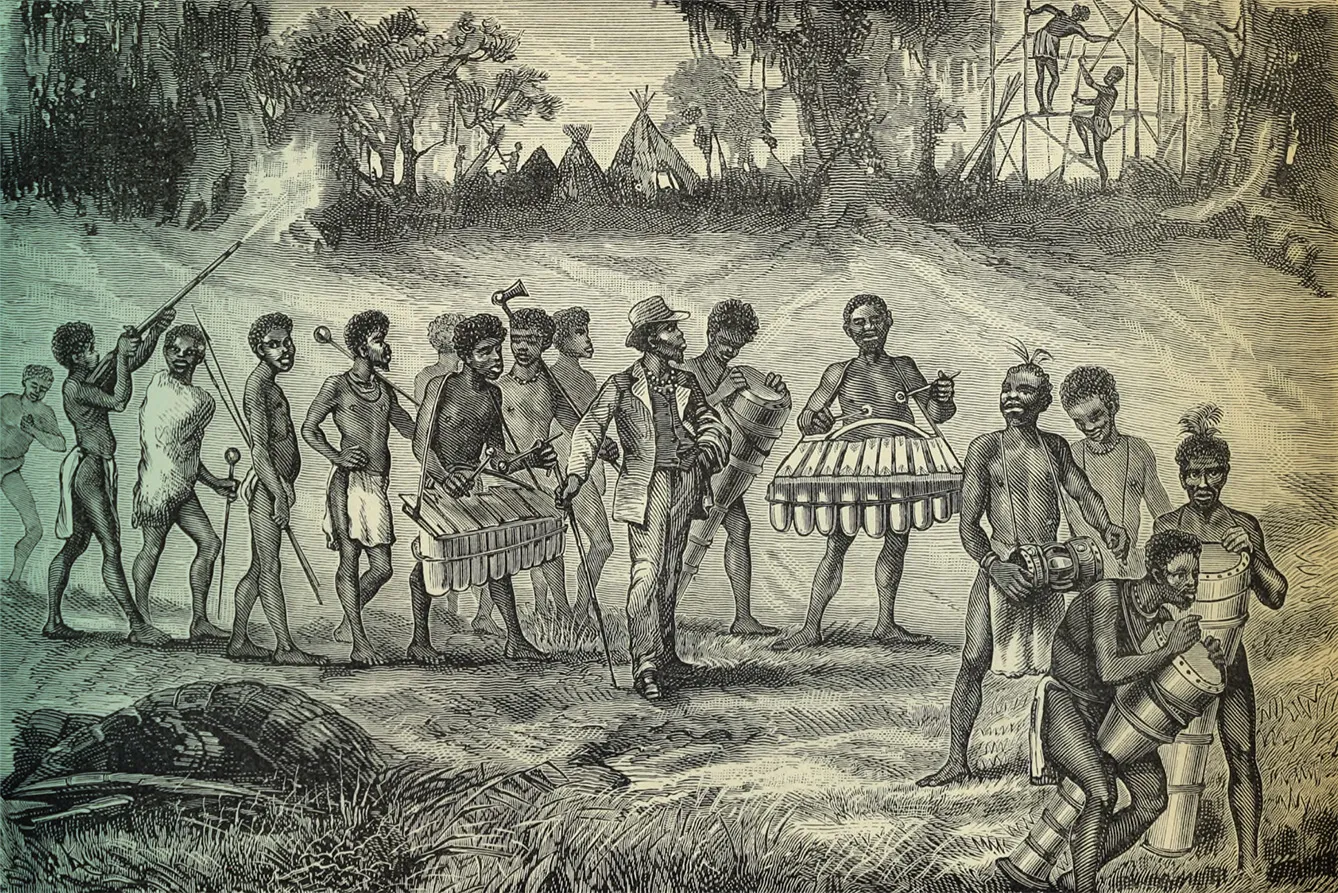

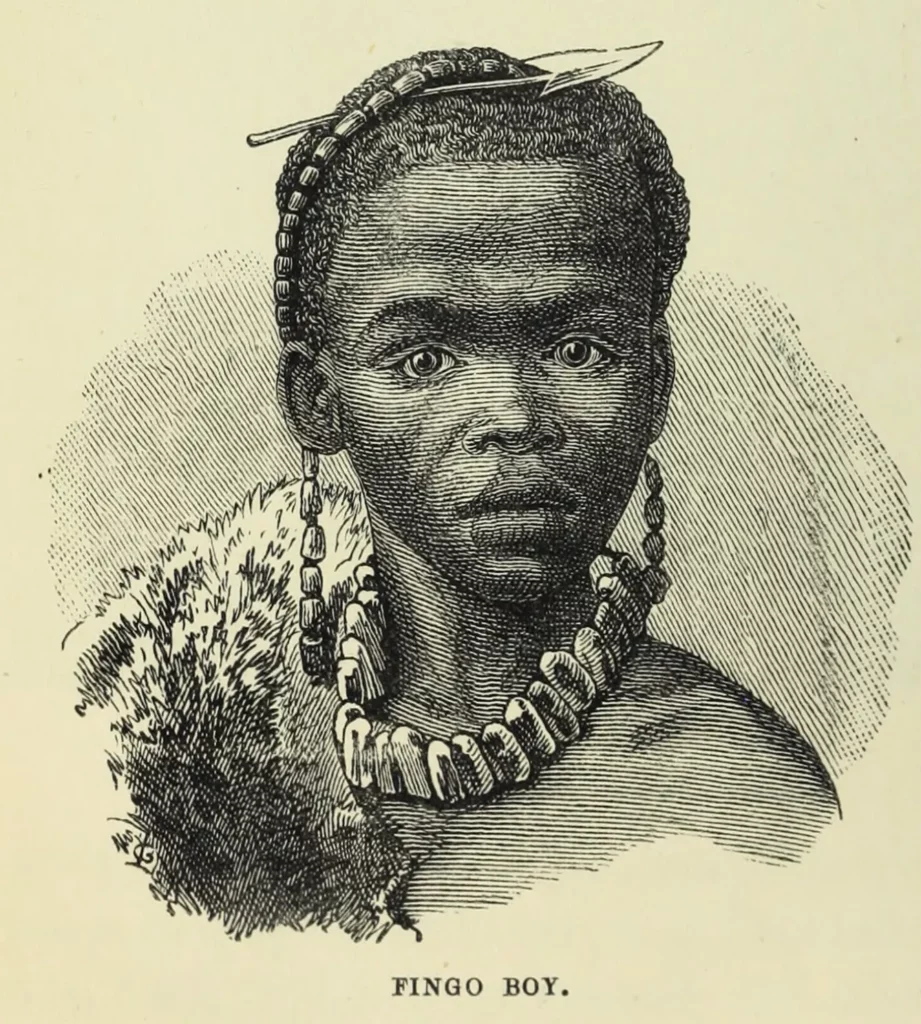

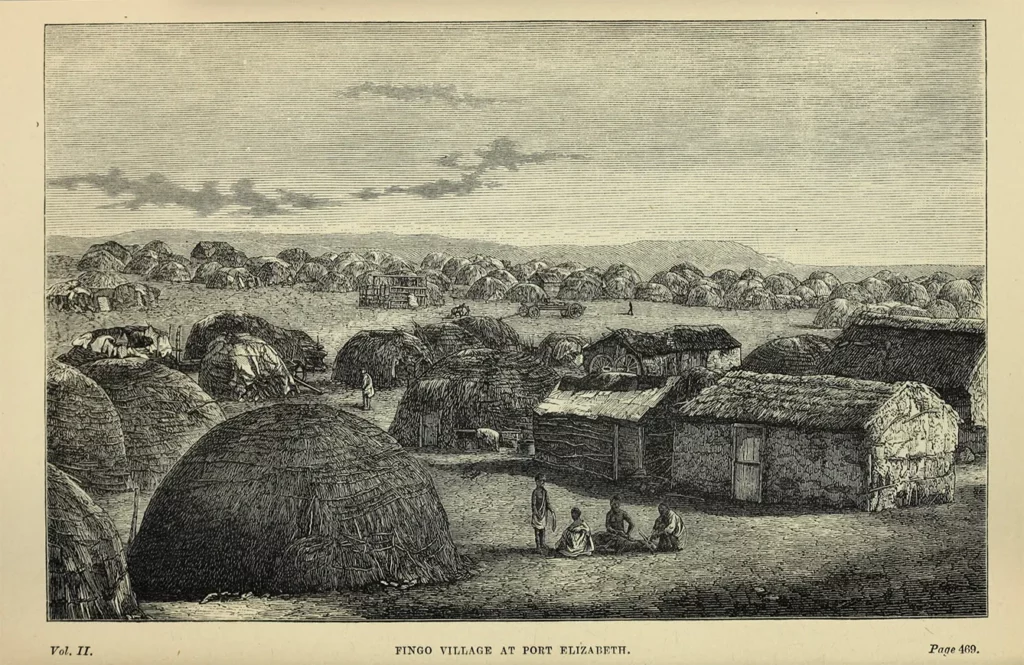

Holub was a natural talent. He moved in African conditions as if he had been born in them, and the locals always took a liking to him immediately. It was thanks to the friendships he made with the locals that he was able to make extensive ethnographic records. These detailed records included scientific notes and drawings about every tribe he met. He described their language, history, culture, cuisine, music, and paintings.

During these two months, he gathered a collection of items he exchanged with locals or which they gifted him. After returning to Cape Town, twenty large boxes of exhibits were shipped to the new Museum of Foreign Cultures that his friend and mentor Vojtěch Náprstek opened in Prague. The museum thus had two major sections: the Náprstek’s North American Natives section and Holub’s African section.

But Holub lasted only a short time in Cape Town as he wasn’t too keen on civilization. Already in 1873, he set out on another expedition into the heart of Africa. Between 1873 and 1879, he undertook three major expeditions that mapped unknown parts of Africa and a deeper understanding of the local people.

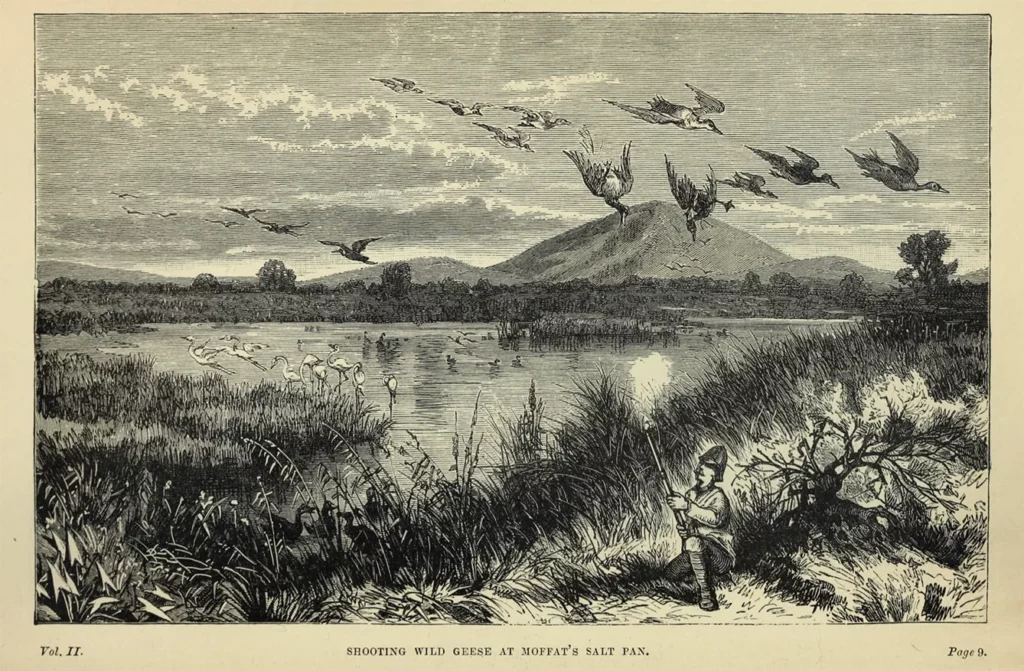

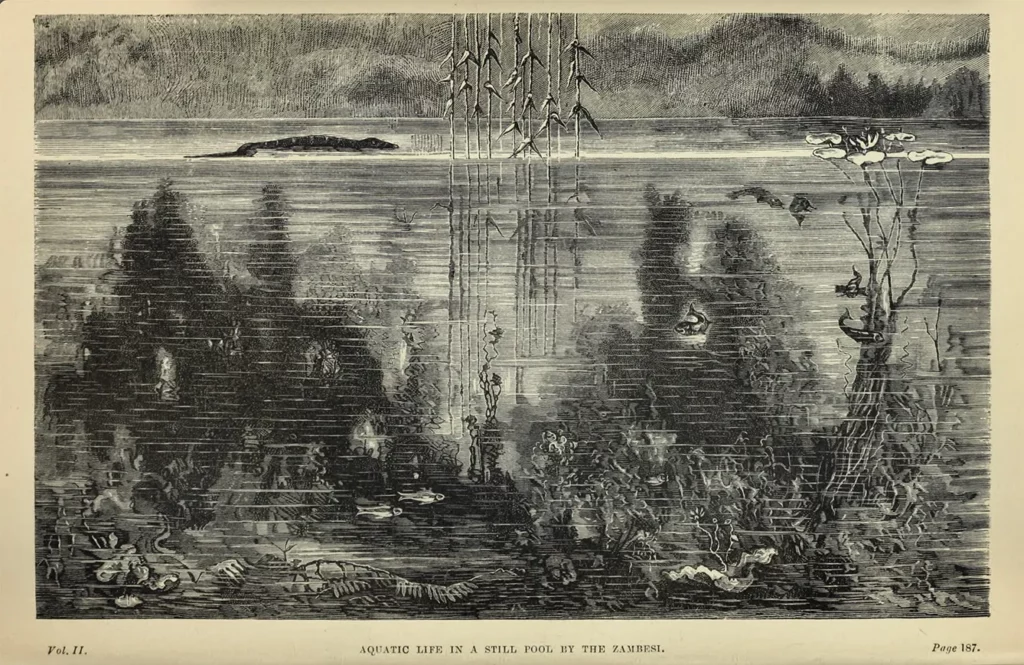

During these expeditions, he explored the fringes of the inhospitable Kalahari Desert, and he was the first to draw a detailed map of the Zambezi River and Victoria Falls. It was also he who discovered the Sanu cave paintings.

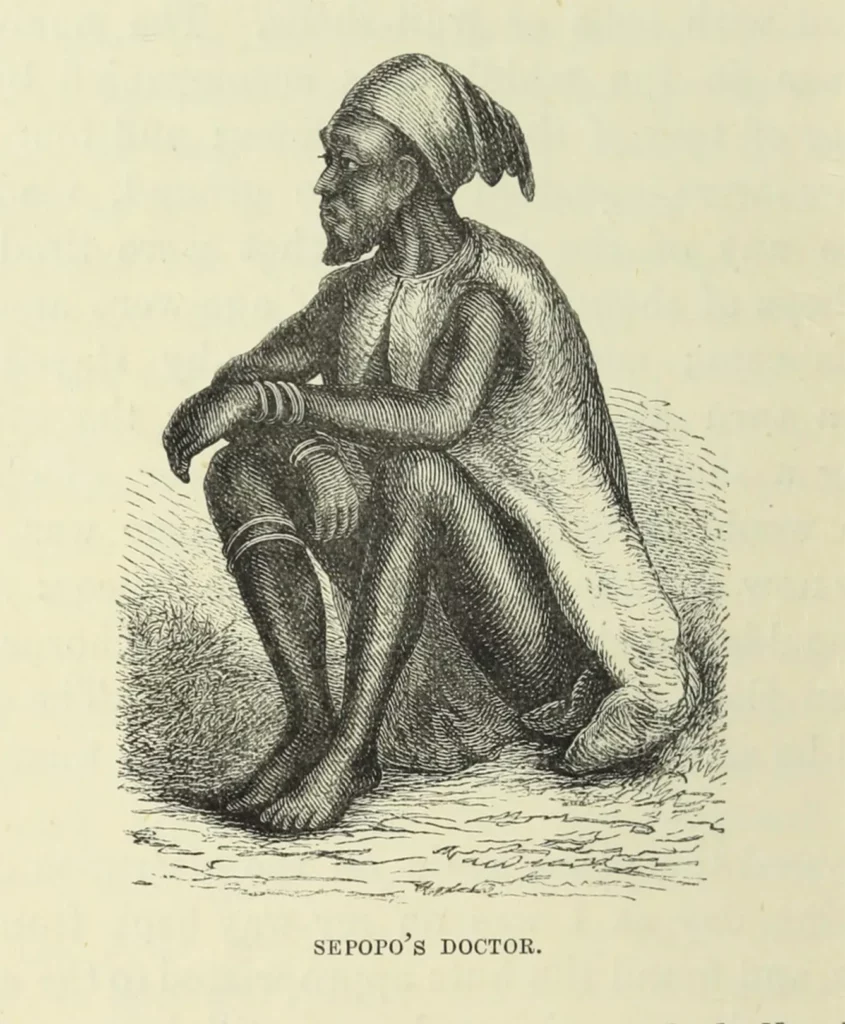

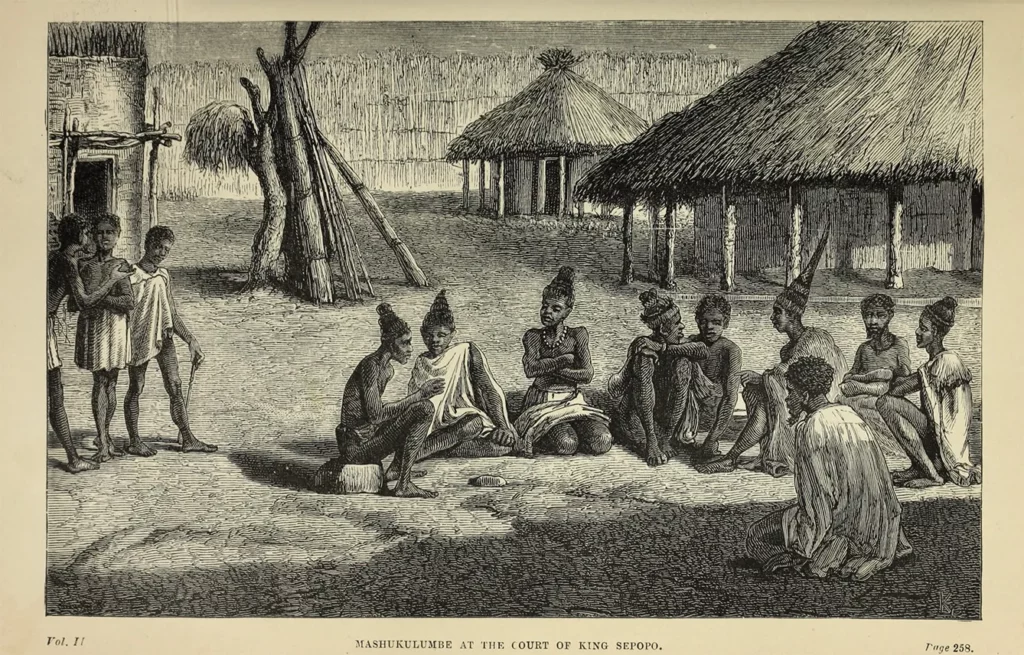

He also visited Shoshone, the capital city of the Bamangwat tribe. On one of his expeditions, he reached Shesheke, the capital city of the feared Lozi tribe. There he met the cruel and dreaded King Sipopo. But luck was on Holub’s side again. Just as the members of other African tribes liked him, so did King Sipopo. By order of the King himself, Holub and his expedition were allowed to travel unrestricted under the King’s protection through Lozi territory as the only Europeans.

Home, yet homesick

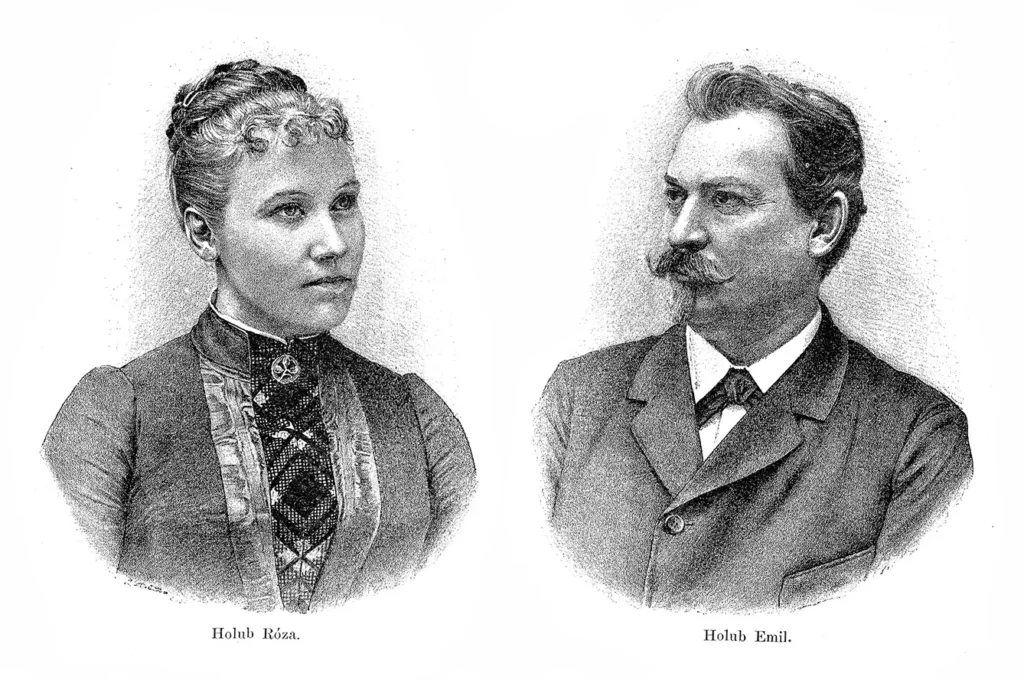

At the end of 1879, Holub returned to Bohemia, where he exhibited African artifacts and published scholarly and popular articles. He also lectured throughout Austria-Hungary. What he did not discover in Africa, he found in Europe: love. In 1883 he married Růžena Hoff, whom he had met in Vienna in 1879. The newlyweds then set off for their honeymoon in Africa on Holub’s second great African expedition.

Růžena Holubová spoke fluent English, German, and Czech. According to historical memoirs, she was also an excellent negotiator. And in case diplomacy failed, Růžena used her second skill: she was a sharpshooter. She was said to be the best with a rifle in the whole expedition.

The Holub couple returned to Africa with a very ambitious plan: to walk from Cape Town to Cairo: from South Africa to the land of Pharaohs, Egypt. The beginning of the five-man and woman expedition, accompanied by a few native pack bearers, went like clockwork. They crossed the familiar territory of the Bamangwat to the territory of the militant Lozi, where Holub reunited with his friend, King Sipopo.

Trouble in Paradise

But by leaving the familiar territory, the expedition also left luck behind. Two members of the expedition soon died of malaria. Then, in the summer of 1886, they unwittingly entered the land of the warlike Mashukulumbas. Holub was the first European ever to visit their territory.

They were ambushed in the wilderness before the expedition could meet anyone and make first contact. Another expedition member was killed, native pack-bearers fled, and most supplies were stolen. This left Holub, his wife, and the remaining expedition member with no choice but to return to friendly territory and regroup.

But the expedition brought bad luck with them. A leopard badly injured one of the group members, and Holub and his wife fell seriously ill. It was clear to all that this was the end of their four-year expedition. So in late September 1887, the three survivors returned to Bohemia.

The Czech African: inspiration for future generations

Unfortunately, Holub never made it back to Africa, even though he desperately wanted to. Until his death in 1902, he and his wife gave lectures on Africa throughout Europe. Holub amassed over 30,000 exhibits and wrote several books about his journeys and adventures.

In his exploration of Africa, he matched his role model, Kryštof Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice, and surpassed him, becoming a role model for a new generation of explorers. And so, in 1947, two young men rang the doorbell of Růžena Holubová’s apartment in Vienna. They introduced themselves as Hanzelka and Zikmund and told her they admired her late husband. But their adventures are a story for another day.