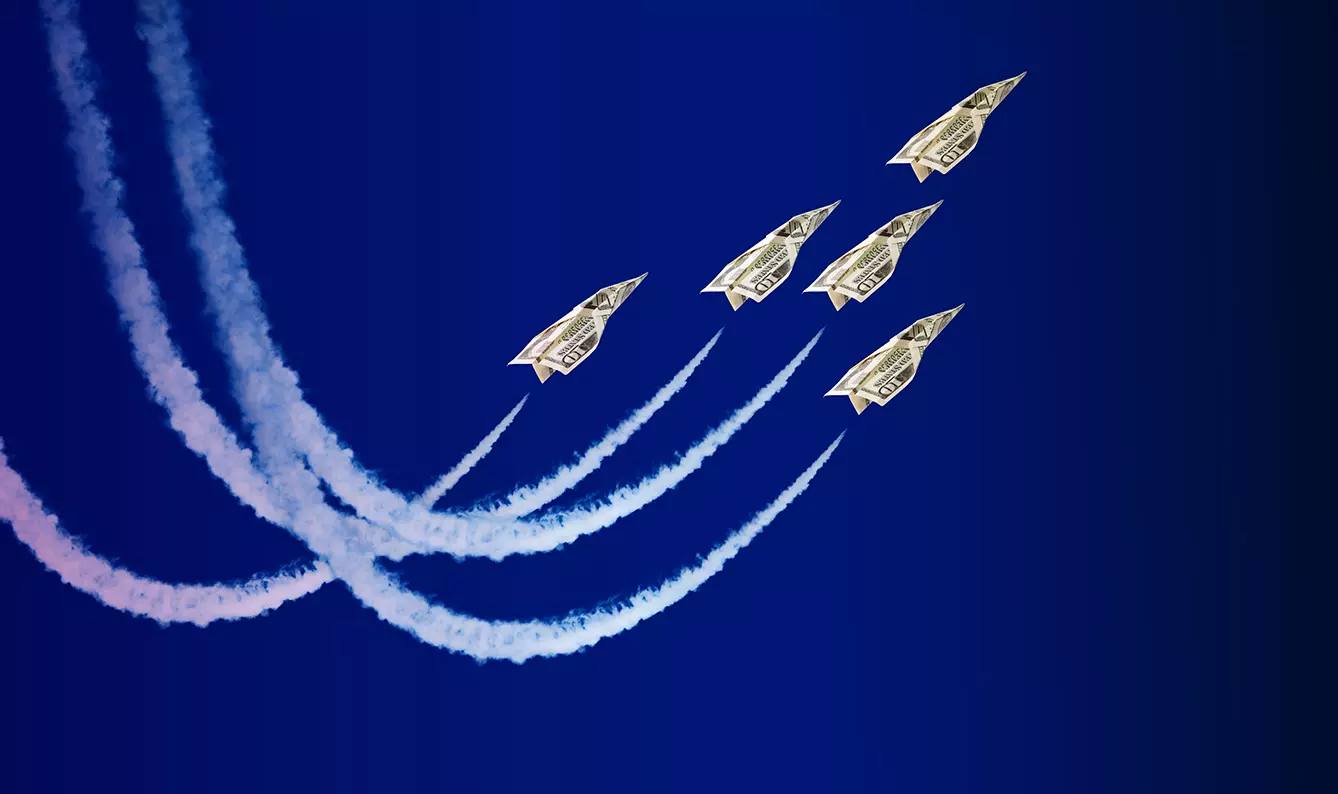

USD 2.1 trillion was spent globally on military expenditures in 2021 – the highest amount in the history of the world in this category. The figures for this year are not known yet, but it is easy to imagine that they will be much higher due to the war in Ukraine. And we all know that – as Liza Minnelli sang in “Cabaret” – money makes the world go around.

If so, and if money nowadays flows in a much broader stream into the budgets of defense ministries, the way it is spent takes on an intensely political tinge. It is not only a matter of each country’s national security; it is also a very political and civil issue as such expenditures can transform the development profile of entire states. High military spending can become the engine that drives the civilizational progress of the whole state. Will it happen to the countries of Central Europe?

Central Europe: first to help

In October 2021, European Council president Charles Michel declared that “2022 will be the year of European defense”. Then it looked like wishful thinking, but now – after Russian aggression over Ukraine – his words sound more like prophecy. But whatever Michel meant, the war in Ukraine showed one thing: Europe was completely unprepared for any military actions.

“Over the last two decades, European militaries have lost 35 percent of their capabilities,” wrote the American think-tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in 2022. Added to this is the lack of strategic thinking at the European level, combined with fragmented planning and dominated by policies conducted through the prism of narrowly defined national interests. As a result, Europe can only be reactive – not proactive – in the face of Russia’s aggressive stance.

Russian aggression has unveiled yet another aspect: European countries are approaching this threat differently. In short, the further away from Moscow, the more lukewarm the reaction. It is no coincidence that it was in the CEE countries that the war in Ukraine provoked the liveliest reactions. They were the first to start helping Kyiv.

Military expenditures and war in Ukraine

It is best seen in data provided by Kiel Institute for the World Economy, which prepares a “Ukraine support tracker” – a unique platform with figures describing how individual countries are helping Ukraine. Under the heading ” Government support to Ukraine: By donor country GDP,” the first places are clearly dominated by Central and Eastern European countries.

By the end of August, Estonia and Latvia had allocated aid to Ukraine worth 0.8% of its GDP; Third is Poland – 0.5% of its GDP. Next is Norway (0.4%), Lithuania (0.3%), Slovakia and Czechia (both 0.2% of GDP). These figures go even higher when mixed with the costs of help for refugees from Ukraine. Together Estonia spent 1.2% of its GDP, Latvia – 1,1%, Poland – 1%, Czechia and Lithuania – 0.6%, Slovakia – 0.4%. For Bulgaria, the cost was 0.3%, and money was spent mainly on help for refugees.

This picture looks different when analyzing data for bigger countries. The USA, Canada, and Great Britain also provided help worth 0.2% of GDP. But France, Germany, Italy, and Spain sent support to the value below 0.15 of domestic GDP. Figures stay the same when mixed with the cost of refugee support—clear proof showing the difference between the two parts of Europe.

“France, Germany, and Italy really do not like each other very much, and none feel threatened. Despite the war in Ukraine, indebted Europeans routinely confuse politics with strategy and defense value with defense cost – commented for think-tank Carnegie Europe prof. Julian Lindley-French, chairman of the Alphen Group, author of the book “Future War and the Defense of Europe.”

Accelerating the process

Looking at the Kiel Institute’s reported figures from a broader perspective, they should not come as much of a surprise. After all, the countries of Central Europe have already shown that they prioritize arms expenditure. It is easy to notice when studying the military spending of NATO countries. The Alliance states are committed to spending a minimum of 2% of their GDP on armed forces. But looking at the latest data, one may see that mainly CEE countries are fulfilling this obligation. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2021, members of the “2% GDP club” were: Greece (3.9% of GDP spent on the military), the USA (3.5%), Croatia (2.74%), Latvia (2.28%), Great Britain (2.22%), Estonia (2.16%), Poland (2.12%) and Lithuania (2.02%). Other states were lagging behind.

The war in Ukraine is only accelerating this process. CEE countries feel much more threatened by this conflict than other states, so they invest more in military equipment. Romania just decided to spend 300 million dollars on Bayraktar TB2 systems from Turkey, started negotiations with South Korea about purchasing howitzers and tanks, and is very interested in buying the “Iron Dome” anti-missile defense system and military drones from Israel. Slovakia bought 76 armored combat vehicles (in three different variants) from Finnish firm Patria and is planning to buy 152 tracked combat vehicles CV90 MkIV from Sweden.

This last purchase is made together with Czechia, which buys 210 CV90 MkIV vehicles from Swedish company BAE Systems Hägglunds. Besides that, Prague started negotiations for 40 Leopard 2A7 tanks from Germany during talks with the United States about buying 24 F-35 Lightning II fighter jets. Lithuania is ready to spend an extra EUR 1 billion on military equipment. The country started negotiations with Germany for the purchase of 120 additional Boxer infantry fighting vehicles.

Polish military expenditures

Vilnius wants to buy new air defense systems, air surveillance systems, and anti-tank weapons. Bulgaria decided to purchase an additional eight F-16 Block 70 fighter jet aircraft for USD 1.6 billion. Earlier in 2019, Sophia already ordered eight such jets.

The biggest buyer of military equipment is Poland, which decided to spend over 2% of its GDP on it (in 2023, it should be 4.2%, the highest budget spending in NATO countries). Just in the last few months, Warsaw has signed contracts for the delivery of 250 M1A2 SEPv3 Abrams main battle tanks (a deal that also includes 116 used Abrams tanks), 48 AHS Krab self-propelled howitzers and 36 accompanying vehicles, three Arrowhead 140 frigates, 48 F-50 lightweight fighter jets, 670 K9 Thunder self-propelled guns and 180 K2 Black Panther tanks from South Korea, bringing Poland one step closer to it goal of having 1,000 of these tanks.

These are only the recent examples of Poland’s highly elaborate (and expensive) plans to purchase military equipment. “There’s a political imperative for Eastern Europe to become militarily self-sufficient without jeopardizing the international cooperation that gives NATO its strength. The region will remain socially divided between West and East as long as it labors under a sense of geopolitical dependency that molds old resentments into new forms,” wrote the “Wall Street Journal,” describing changes in the attitude of European countries in the context of the war in Ukraine.

But when the forest is cut, the chips fly. The rise in military spending will have political and economic consequences. Which will be seen first? It looks like political ones.

Central European military expenditures and Russian aggression

“The exercise of Russian aggression has allegedly strengthened the EU in two fashions: enhancing unity between its Member States and prompting capitals to take matters of security and defense more seriously. This narrative is only partly true. It neglects a third, and perhaps equally consequential dynamic, namely the (at least temporary) increased influence of the EU’s eastern members,” wrote the prestigious Brussels think tank Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS).

“What can already be clearly observed is the growing relative legitimization of the foreign policy perspectives of the EU’s newer members. No longer seen as part of the problem in impeding an EU-Russia rapprochement, these countries are currently playing a major role in shaping the EU’s priorities on the Ukraine file,” CEPS observed in its analysis.

This new dynamic will break with the previous trend built around the rule: that the further away from Moscow, the more lukewarm the reaction. There was a perception in the Western world that Russian aggression had become a threat to all for two reasons. First, it broke with the pre-existing political status quo. Secondly, the use of the army has become a form of breaking taboos – after all, until 24 February 2022, no one seriously thought it was possible to resort to the argument of violence.

Now it is no longer impossible. There is no way back to the status quo ante. A new one will begin to take shape – and in it, the ability to respond to crises, including those of a military nature, will become a much more critical skill than before. Whoever is better able to deal with this reality will see their political ratings soar.

This new rule will not only apply in Europe. As American political scientist Walter Russell Mead noticed: “Mr. Putin’s war hasn’t only destabilized Eastern Europe. From the Middle East to Central Asia, governments face discontent as supply shocks raise food and energy prices. From Turkey to Kazakhstan, countries whose economies have deep ties to Russia struggle to navigate Western sanctions. The soaring dollar and global inflation make matters worse. This will be a bitterly hard and hungry winter for millions”.

Central European countries were the first to experience the shock of neighboring an open, full-scale war. But watching their reaction also shows that they will be the first to adapt to the new reality. In the near future, this will prove to be a vital political resource for the modern world.