People have a natural affinity for the sweetness of sugar. However, the same cannot be said about handling it in the traditional form of sugarloaf. Described as cones or lumps, large sugarloaves were the standard form of this sweetener at the beginning of sugar beet processing in the early 19th century. That all changed when the wife of one of the sugar producers cut herself trying to slice it.

Before sugar cubes

Raw sugar was refined by the process of boiling and filtering, and then it was shaped in earthenware forms and wrapped in paper. The result was a hard, white lump that was easy to store and transport but not so easy to portion. There was also a wide array of tools used to portion it, anything from cutters and nippers to mortars, hammers, and chisels.

Of course, few people would have given these difficulties a second thought if it were a job that could be handled entirely by servants. However, sugar was costly, and portioning it was very messy, leading to a lack of accountability. Purchasers simply did not trust their servants enough with such a valuable product that could so easily be stolen in tiny increments. This led to lock-and-key sugar bowls and the establishment of sugar portioning as a job handled by the mistress of the house.

Such was the role of Juliana Rad, wife of Jakob Christof Rad – a Swiss-born entrepreneur from Vienna and director of a sugar factory in Moravian Dačice, located in modern-day Czechia. The factory had been flailing when he took over, but Rad was able to turn things around by adding new machines and even introducing the first steam engine to support the process.

Blood, sweat, and tears

However, the real advance came with the blood. One day in 1841, Rad witnessed his wife Julianna badly injure herself during the portioning of sugar. Inspired by her wound and the sight of the blood, he set out to find an alternative to sugarloaves. One year later, the director of the Dačice factory was ready to apply for a patent for sugar cubes. The solution involved pressing the milled sugar into standard cubes using partially dried sugarloaves.

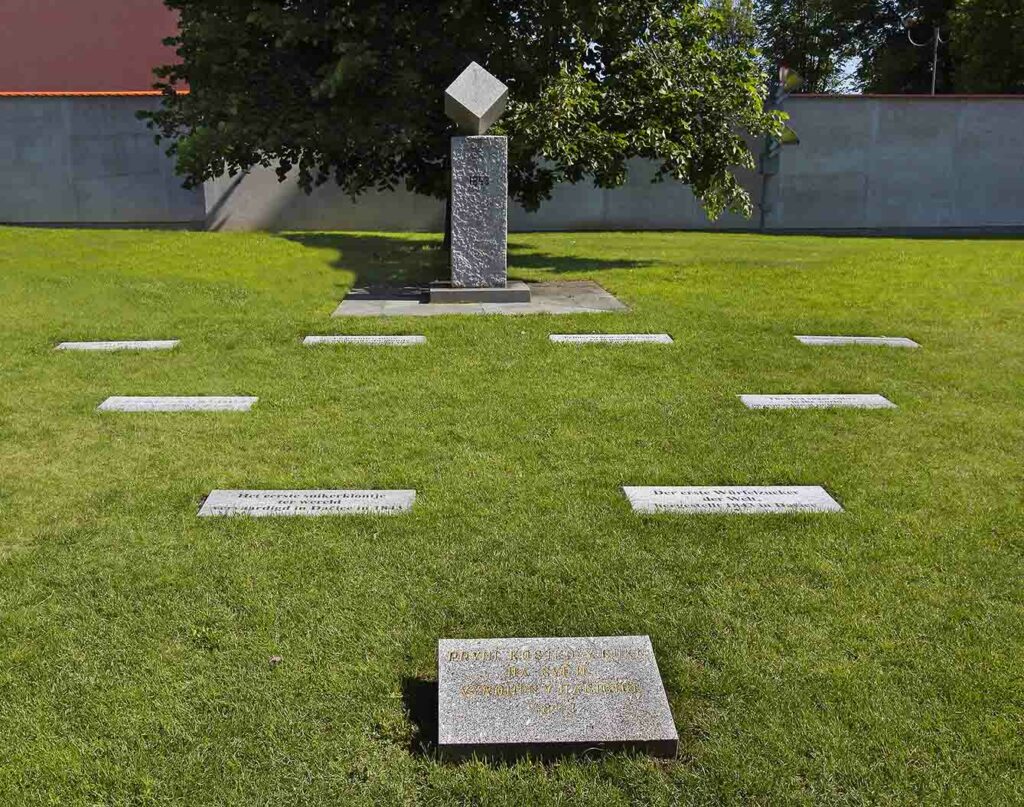

In the following years, virtually every country in Europe bought Rad’s patent and introduced the standard sugar cube, ensuring equal sweetness in every teacup – and saving the hands of sugar portioners everywhere. Rad’s name was forgotten for years; however, in 1983, a small granite cube was built to honor the invention that had stopped the sugar bloodshed some 150 years earlier. Now the invention of the sugar cube is a part of the collection in the Dačice Municipal Museum.