At the risk of only a slight simplification, we can call this whole part of the world a Soviet orbit that, to a certain extent, supported the USSR’s vision of history and social affairs. It followed the Soviet notion of Nazism (which differs significantly from the Western concept of Nazism, as evidenced by the current “anti-Nazi” war in Ukraine) and the myth of the Soviet Union as the main anti-Nazi force that shaped the historiography of the region. Fittingly, along with historiography came monuments.

The rise and fall of the Victory Monument in Riga

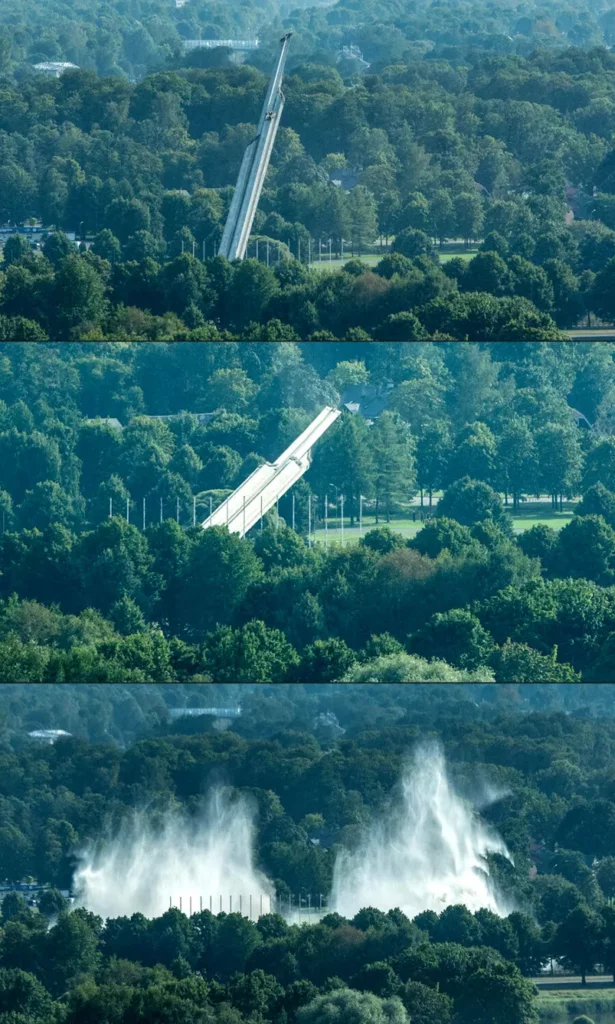

The 80-meter-tall Victory Monument to the Red Army that was famously demolished in Latvia’s capital Riga on 25 August 2022 was an important symbol and the latest chapter in the long history of building and demolishing such souvenirs.

Officially known as Monument to the Liberators of Soviet Latvia and Riga from the German Fascist Invaders, but simply called Victory Monument, it was erected as late as 1985 to commemorate the day Red Army conquered the city from Nazi Germany.

Although Soviet and Russian history portrays those events as “liberation,” in the light of subsequent decades under communism and Soviet command, they are not seen as particularly “liberating” across Central Europe. Hence the resentment against both Soviets and symbols of their power.

In the case of the victory monument in Riga, two groups of figures – one representing the peaceful homeland, the other – peacemaking troops, represented the typical Soviet symbolism legible for the masses, while a tall central obelisk made it truly monumental – so it could both be seen and dominate the space.

That’s why (and maybe because of association with “Moscow’s finger”) Alexandr Buagev’s design was not appreciated, to say the least. So when Russia invaded Ukraine earlier in 2022, Riga, the capital of the NATO Baltic state, after years of popular pressure, decided to demolish its Victory Monument.

Victory monuments across Europe

The obelisk fell to viewers’ applause, but to protests from the Russian minority – and Russian officials. Leonid Slutsky, chairman of the international committee of the Russian State Duma, quoted by Russian TASS press agency, called it “a day of shame in Europe,” once again alluding to neo-Nazism, supposedly found in today’s Ukraine.

For Russians, the “Great Patriotic War,” as World War Two is called in their country, is a staple of national identity. And the whole of Central Europe is filled with monuments – some of them actual Red Army cemeteries – that Russia’s diplomacy defends.

Five years earlier, in October 2017, Russia demanded Bulgaria restore a monument’s original look to the Soviet Army in Sofia’s Lozenets district. This time the monument had been painted to disguise Soviet troops as American superheroes: Captain America, Superman, Wonder Woman, and Ronald McDonald holding an American flag instead of a Soviet banner.

This was not the first time the monument had been altered. After Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014, the soldier in front was painted in the colors of the Ukrainian flag. Later that year, two of them were painted in Poland and Ukraine’s national colors to commemorate the Soviet Katyn massacre. One year earlier, the monument turned pink, with inscriptions excusing Czechs and Slovaks for Bulgarian participation in 1968’s invasion of Czechoslovakia.

Felix Dzerzhinski beheaded

As historical memory is a battlefield, little there is to wonder that former symbols of power and/or terror (like this abandoned airfield in Croatia or the House of Terror in Budapest) are turned into monuments, and the other way round – monuments that are considered signs of power and terror are being repurposed or demolished.

Among the famous examples, there is Warsaw’s monument of “Iron” Felix Dzerzhinsky – he was born a Polish noble and died a member of the Bolshevik secret police (infamous Cheka, and later OGPU) creator. When his monument, in a square named after him, was demolished back in 1989, the statue itself was entirely destroyed. Rumor has it that the workers responsible for the act tied the figure by the neck as if on gallows so the monument would be beheaded during the fall.

Among perhaps thousands of such Communist souvenirs, some are more, some less controversial. Sometimes monuments – such as the ex-Soviet tanks in dozens of cities – are the most important landmarks in the area. Sometimes, no matter the narrative, those landmarks have unique artistic qualities.

Whatever the case, the historical memory of Central Europe is constantly being reassessed. The fate of the Victory Monument in Riga is the perfect example.