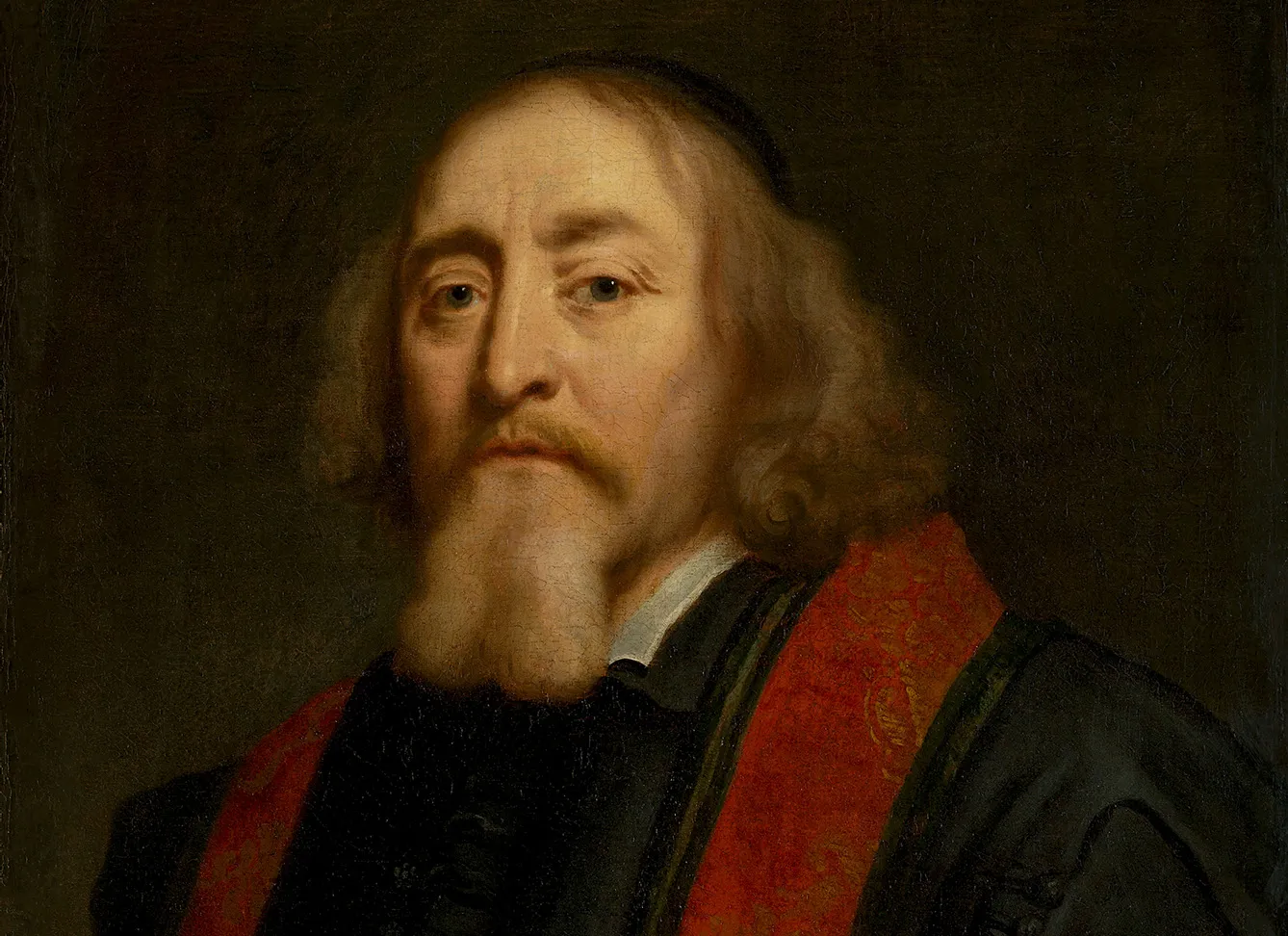

Fate is sometimes merciless. Jan Ámos Komenský, also known as Comenius, could tell us all about it. He had to work hard all his childhood in the family mill in Moravia. At twelve, the plague deprived him of his entire family and forced him to flee his native region because of the war. Many would ask, “Is there anything good in life for him?”

Comenius’ lifelong roller coaster

As they say, everything bad is good for something. After the initial tragedies of his life, Comenius was taken in by a prominent nobleman who sent him to study. Komenský was a very gifted student and was later sent to a secondary school in Herborn, Germany, where he also went to the Protestant University of Heidelberg. During his studies, Comenius’ sincere love for God began, which did not leave him for the rest of his life.

After returning to Bohemia, he became a teacher and preacher for the Unity of the Brethren, a Protestant church. Another religious war came when everything seemed to have calmed down in Comenius’ life. His wife and two children died of a plague brought into the country by invading Catholic troops. As a Protestant, Comenius becomes an enemy of the state, and his books are publicly burned.

But during this period, he would write one of the most important books of the Baroque, Labyrinth of the World and Paradise of the Heart. It is a philosophical-religious-satirical work whose theme is exploring the ultimate meaning of human life and its work and endeavor.

Jan Ámos Komenský: from teacher of children to teacher of nations

Despite successfully hiding from religious persecution, in 1628, Comenius had to flee to Leszno, Poland, which became a haven for many Unity of the Brethren members. It is in Leszno that he writes most of his 200 books.

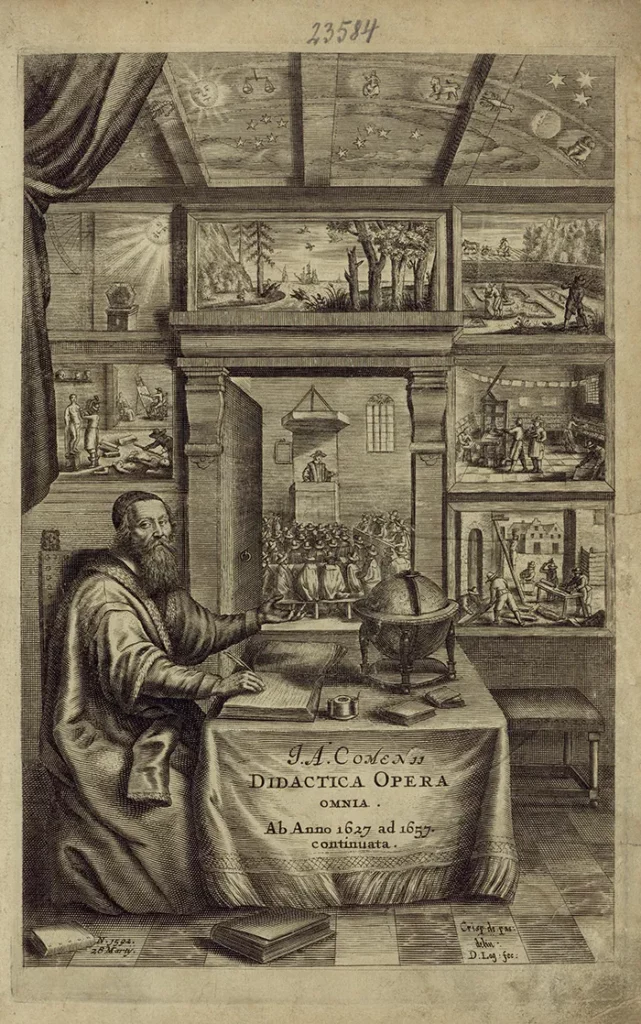

Among the most important is The Gate of Languages Unlocked, which has become an essential textbook for teaching most languages. The book spread from Leszno worldwide, and not long after its publication, it was used from Portugal to Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq). The teaching methods that Komenský introduced are still used in teaching most languages worldwide today.

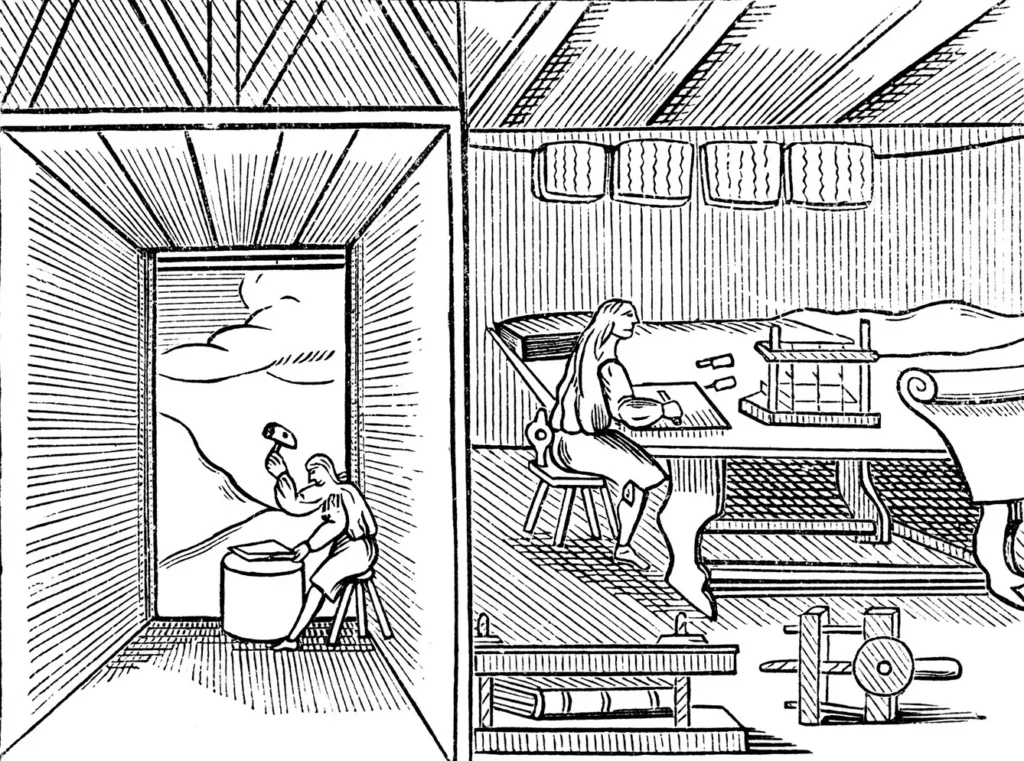

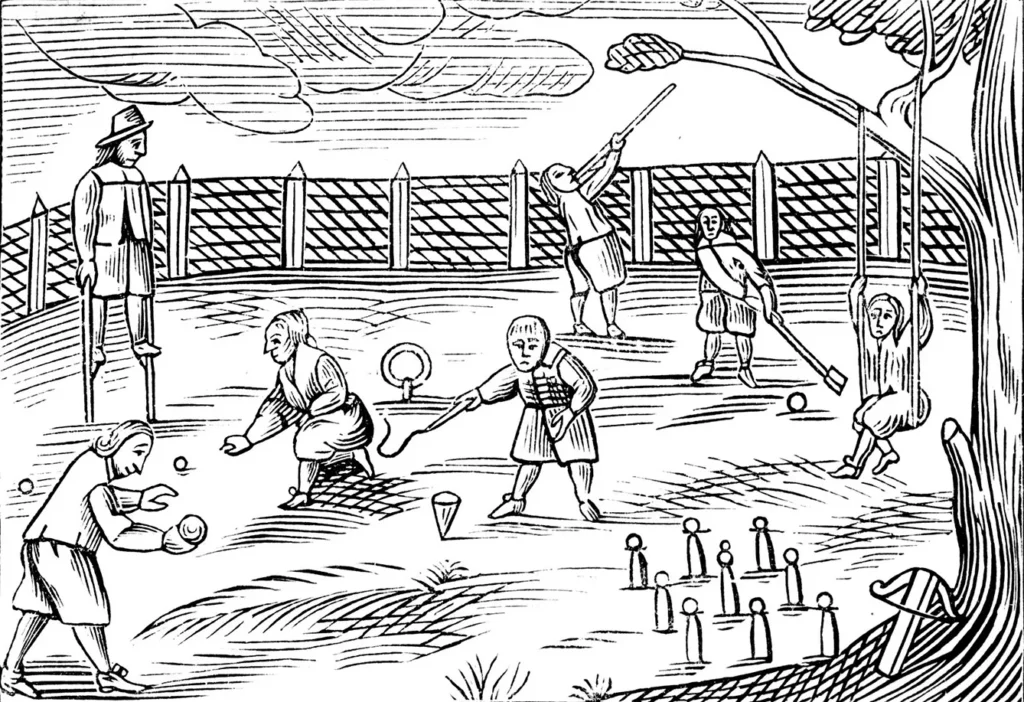

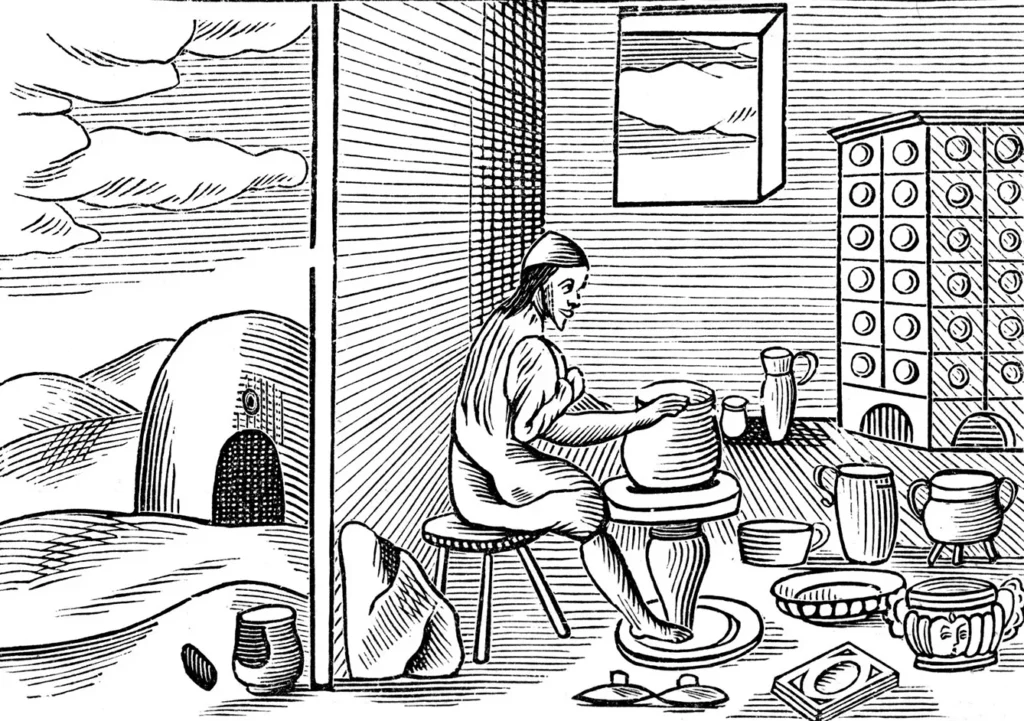

Another of Comenius’ world-famous works was Orbis Pictus, The World in Pictures. As a teacher, Comenius saw that children had trouble learning from books full of text. So he incorporated picture material into his textbooks. He then described this method in Orbis Pictus, which he sent worldwide. Unsurprisingly, Comenius’ book, with his new approach, “School by Play,” was a worldwide success. And like all of Comenius’ methods, Orbis Pictus is still used today.

If you are already anxiously awaiting the next tragedy that would spice up Komenský’s life, you have understood his story correctly.

Escape from Leszno and the troublemaker life

In 1655, Protestant armies led by the Swedes invaded Poland and began to plunder the country. When the Swedish troops stood over Leszno, the Protestant refugees (including Czechs) opened the city’s gates and handed them to the Swedes without a fight. This was a betrayal that the Poles never forgave. When they reoccupied the town a year later, they burned it down and expelled all the Protestants, Komenský included.

During this burning of Leszno, most of the extensive library was burned, including most of the originals of his works. A tremendous loss, however, was the unfinished Czech-Latin dictionary on which Jan Amos had been working continuously for the last 40 years.

After leaving Leszno in 1656, Comenius found refuge with friends in Amsterdam. The Netherlands welcomed the renowned teacher and philosopher with open arms. During his Dutch exile, schools in Sweden, Holland, and Hungary were undergoing reform according to his principles.

He devoted himself diligently to his theological, cartographic, philosophical, and pedagogical work, aiming at the “repair of the world.”

Working for the nation and God

At the time, however, Comenius was described as having a complicated personality, and coexistence with him was said to have been not at all easy. He was always working, sleeping less than four hours a day. For the rest of his life, he tried to restore his library and rewrite the Czech-Latin dictionary. Today we use the term workaholic.

Tested by fate several times, he never let himself be broken. He considered a lifetime of education and the proper upbringing of youth to be the only possible path to a world without war. To this, he dedicated the rest of his life. Komenský died in 1670 in Amsterdam, but his grave was discovered by Czech patriots only 200 years later in another Dutch town – Naarden.

He also became a great inspiration for all Czech patriots. Take painting number 16 of the Slavic Epic as an example—a colossal artwork dedicated to Jan Ámos by the Czech painter and patriot Alfons Mucha.

Komenský never forgot his beloved homeland. In his last will, he wrote to the Czech nation: “I cannot forget you, Czech nation. I trust in God that, after the wrath has passed, the rule of your affairs will return to you.” Finally, Comenius appealed, “Have a love for the truth, as Master Jan Hus taught us. Remain united, turn to Christ, love one another, and care for the younger generation. Live, O nation consecrated to God, and do not die.”