Kryštof Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice was the first historically significant traveler in Czech lands and one who could be described as a Renaissance man. He was a poet, a writer, a painter, and a music composer who knew seven languages. He was also an important nobleman, an officer in the army, a diplomat, and a historian. His love of diplomacy, languages, and the history of Bohemia and the world set him to become a distinguished traveler. In 1598, after serving in the war against Turkey, he finished his career as an officer and turned to travel.

A trek to the Holy Land

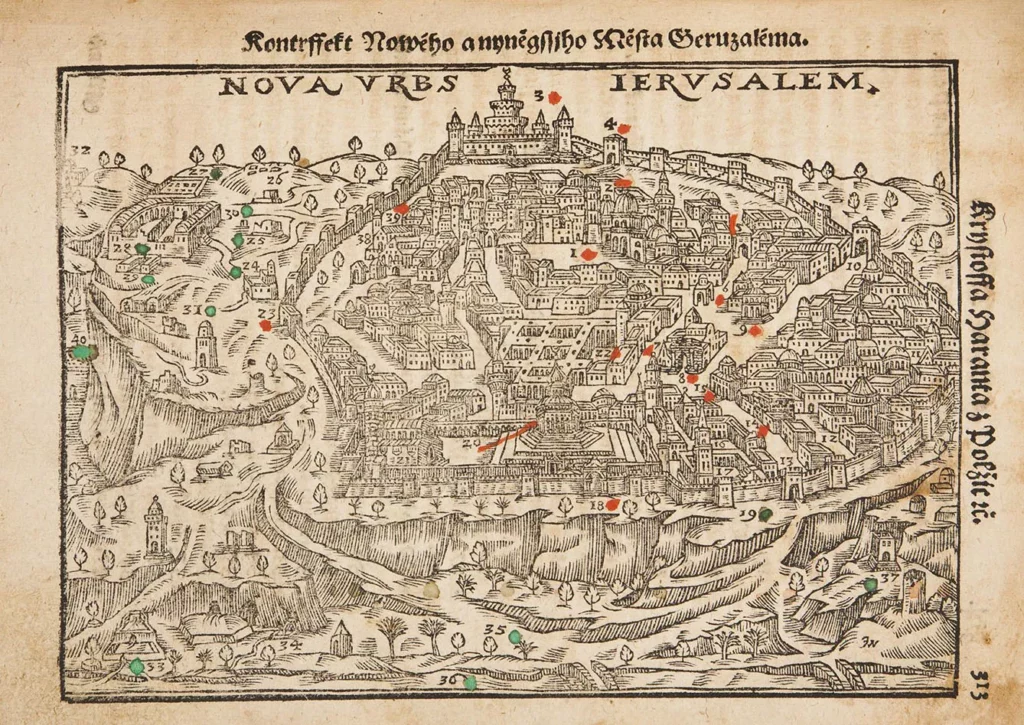

He made the journey with his brother-in-law, Heřman Černín. Kryštof Harant wrote a travelogue, which he even illustrated himself during his travels. However, it is questionable how 16th-century readers reacted to his illustrations. For example, the dolphin in Kryštof Harant’s drawing looks more like a winged shark. The first steps of the journey took Harant and Černín through the Czech and Austrian countryside. Then they crossed the majestic Austrian Alps and headed to Venice, Italy. There, they decided to get themselves a set of pilgrim’s robes and go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

After a harrowing voyage, when their ship nearly sank under the onslaught of the waves, Kryštof Harant and Heřman Černín landed in present-day Israel and set off to Jerusalem. In the Holy City, they, among other sights, visited the Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified, and the Holy Sepulchre. In recognition of their service in the defense of the Holy Land, they both received the title of Knight of the Holy Sepulchre.

A double struggle for life in the land of the pharaohs

From Jerusalem, they traveled across the Sinai desert to Cairo, Egypt. During this journey, their caravan was ambushed by the Arab desert bandits, but their attack was repulsed. After reaching Cairo, they sailed up and down the Nile, exploring the ancient land of the Pharaohs.

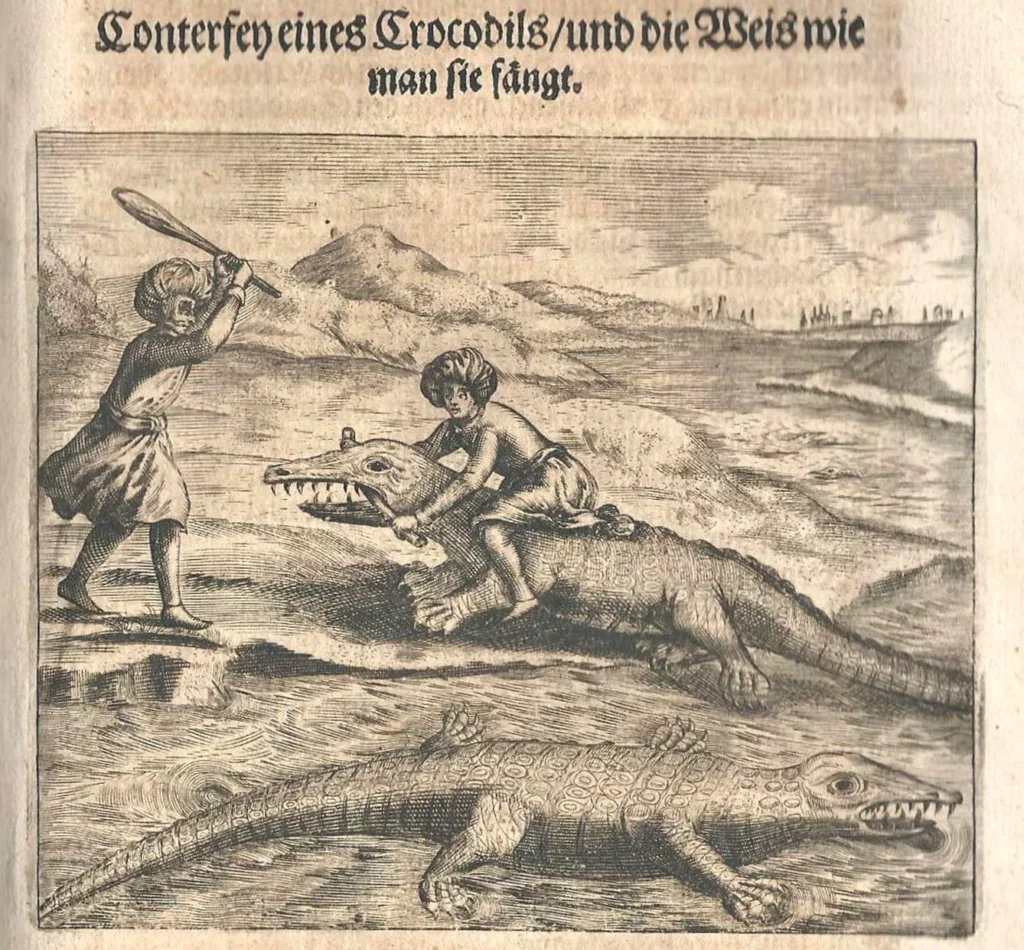

During the Nile voyage, fate tried to take Kryštof Harants life for the third time when a crocodile tried to eat him. For this attempt on his life, he made a very unflattering entry in his travelogue referring to the ancient creature. It went like this: “a four-legged beast, long and low, ugly, terrible and noxious. (…) A cruel beast.”

They then sailed home through Alexandria via Crete and Venice. In Bohemia, Kryštof Harant spread his travelogue among the local elite, establishing himself as a traveler, explorer, and distinguished adventurer. A book of Christopher’s travels for the general public, including his illustrations, was published in 1608 under the title Journey from Bohemia to the Holy Land, by way of Venice and the Sea.

Traveler, nobleman, diplomat

After his return to Bohemia, Kryštof, a retired officer and traveler, served at the court of Emperor Rudolf II, who moved the seat of the Austrian monarchy to Prague. After the accession of his brother Matthias Habsburg to the throne, Christopher was called to the diplomatic service.

He traveled to the Spanish Royal Court for three years and was an envoy of the Austrian Emperor Matthias of Habsburg. In Spain, he continued his passion for travel. Among the most influential journey in the Iberian peninsula, according to Kryštof himself, was a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, where the remains of St. James are buried.

When Christopher returned to Bohemia in 1618, he returned to a very different political and religious atmosphere. The Czech lands had become a pressure cooker that was about to explode. And it indeed did explode on May 21, 1618, when the Bohemian Protestant Nobles rose against the Austrian Emperor.

There were several reasons for the uprising: the suppression of religious freedom, the imposition of censorship, and the persecution of Czech nobles who opposed the Emperor. And where was Christopher Harant? Right in the middle of it all. Under the pressure of events, he converted to Protestantism, something he began to think about in Spain, according to his private notes.

The last expedition of the brave traveler

It was also around this time that he embarked on his last expedition as a traveler. His last foreign destination was Vienna, Austria, in 1619. However, he did not set out for the capital of the Austrian monarchy as a pilgrim in pilgrim’s robes this time. Instead, he went as a commander of the Protestant artillery in military uniform to conquer the monarchy’s seat.

But the conquest of Vienna was the first thing in Kryštof Harant’s life that he failed to do. The Czech siege of Vienna failed, so Kryštof returned to Bohemia for one last time. From that moment on, the war lasted just under two years. At the end of it, for Harant, came death. He managed to escape the Egyptian crocodile but could not escape Prague’s executioner.

On 21 June 1621, a podium was erected in Prague’s Old Town Square, on which 21 Czech nobles, who participated in the anti-Austrian uprising, were to be executed. Kryštof Harant was the third one to lose his life. Ironically, Heřman Černín was among the judges – the same one who traveled with Harant through the Arab world. According to later evidence, Černín tried to defend his friend even shortly before his death. Unfortunately, it was too late.

Even after Kryštofs’s death and despite his defiance of the monarchy, the Austrian Emperor still held him in high esteem. His wife was the only one of the widows who received the Emperor’s permission to bury her husband. After 57 years, in 1678, a book summarizing his travels and life was published in Germany at the expense of his nephew Kryštof Vilém Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice under the title “Der Christliche Ulysses: The Christian Odyssey.”

Despite his tragic end, today’s generations are reminded of Kryštof Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice by his exciting and readable travelogues, his bravery on the battlefields during the war against Turks and the Czech Nobles Uprising, and his classical and religious music compositions. Then there is his eternal monument in Prague’s Old Town Square: one of 21 white crosses commemorating his sacrifice for his beloved country.