Despite Russia’s declared intention to keep Romania’s treasure safe as a short-term solution, even after a century of negotiations, the treasure remains buried somewhere under the Bear’s nose, still adorning Moscow’s vaults and yearning to be brought back.

Trying to remain above the fray

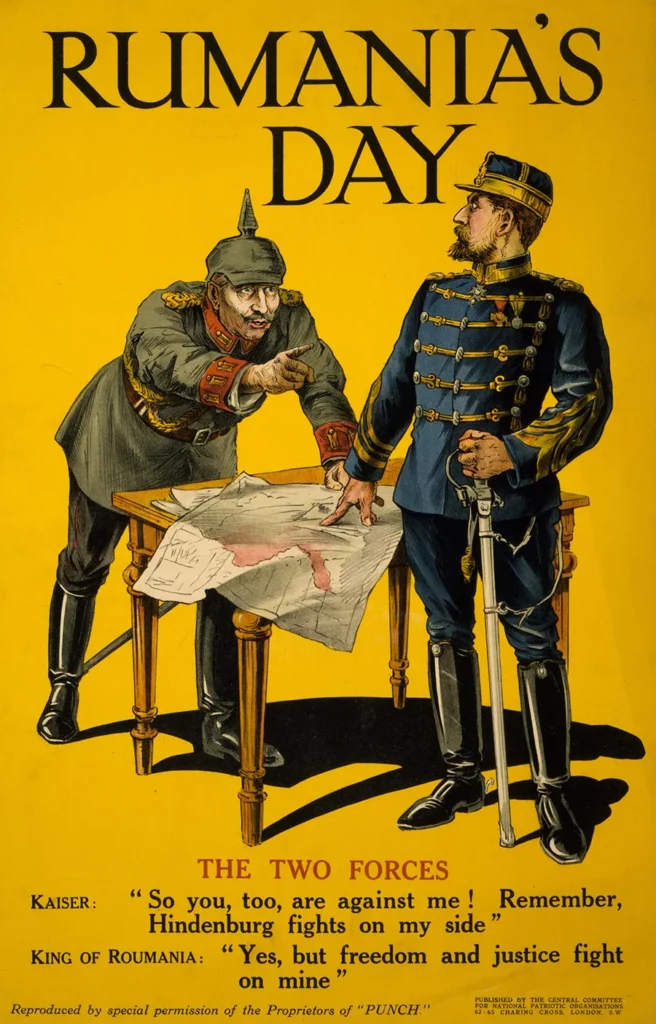

By the time World War I began ravaging Europe, Romania was surrounded by warring empires and was in no rush to enter the fray, maintaining its neutrality until August 1916. Then, it went to the trenches side by side with the Allies. Despite making progress on the battlefield, the enthusiasm quickly faded, and a year later, Romanians found themselves fighting in the Carpathians while German troops were strolling through the boulevards of the “Paris of the East.” Because of this, radical action was taken to protect the country’s national treasure by sending it to Moscow.

Since the Romanian royal family was closely tied with dynasties across both the Entente and Détente, it was quite difficult to choose where to draw the line and enter the war. For instance, King Ferdinand I headed a branch of the Hohenzollern (Germany), his wife Queen Marie being the granddaughter of Queen Victoria (UK), with numerous other members finding themselves at the center of the Serbian, Bulgarian, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, etc. ruling monarchies.

After two years of indecision, Ferdinand decided to follow the people’s desire. He declared war on Austria-Hungary (Détente), with three Romanian armies crossing the border and advancing to retake Transylvania. Despite initially meeting little opposition for Romania, the consequences of entering the war at a later stage proved twas like a Russian doll – as soon as progress was made, new complications surfaced.

Efforts to safeguard the national treasures

With the German offensive approaching Bucharest, the government, military, and royal family moved to Moldova (some 150 km from Bessarabia’s – then Russian – borders), along with the National Bank of Romania and its assets. As most of the administration regrouped in Iași, the government decided to move parts of the country’s national reserve abroad for safekeeping, giving in to Mossolov’s insistences and sending train after train to Moscow with treasures worth almost LEI 350 mln at that time.

Thus, after signing a treaty that guaranteed the safekeeping and return of the assets with the Russian representatives, on 14 December 1916, the first train was loaded with 1,735 crates with gold coins and 3 with pure gold ingot bars worth over LEI 314.5 mln, alongside another 2 trains with the royal family’s jewelry (worth just for their materials LEI 7 mln), representing a large portion of the NBR’s mandatory 40% reserve needed to back the currency. When they reached the destination, the assets were deposited in the Kremlins’ Arms Room, a chamber managed by the National Bank of Russia. Between January – February 1917, all the items were inspected, certifying that “all valuables checked, either inventoried or weighted, proved to be – in terms of both quantity and value – in conformity with the National Bank of Romania’s statements,” with the Treasure including a variety of foreign coins from British pounds and Austrian crowns to German marks, etc.

As the Romanian government feared another German offensive, another train was prepared to leave for Moscow in July 1917, this time taking not only the NBR reserve but also valuables from the Romanian Academy, CEC Bank, National Archives, National Antiques Museum, State Pinacotheca, and several other companies, ministries, national patrimony sites or religious institutions. This time, the three wagons carried to Moscow another LEI 7.5 bln in assets, with the NBR gold and other NBR’s valuables amounting to over LEI 1.6 bln, bringing the total of Romania’s gold deposited in Kremlin to 91.48 tons of pure materials (close to nowadays Romanian national reserves of 103.7 tons).

An unexpected revolution threatens the agreements

That August, a new protocol was signed, mentioning that “the return of the entire treasure of Romania was guaranteed by the Russian Government,” without anyone expecting that the latter might get overthrown during the October Revolution. Hence, by January 1918, Russia’s Council of People’s Commissars cut diplomatic ties with Bucharest and seized the Romanian treasure, promising to” return it to the Romanian people” and not the oligarchy.

Throughout the peace negotiations, Romanian officials tried to bring the assets back, yet the first restitution only happened in 1935, when 1.443 crates of archived treasures were returned, most of which presented signs of usage, along with LEI 198,000 of banknotes. After another two decades passed by, in 1956, the USSR returned another part of the Treasure, this time including 39,000 artistic and historical artifacts (some dating to the 4th century), alongside 32.65 kg of gold.

After the USSR collapsed, Romania signed a treaty in 2003 establishing a joint commission on this matter, which held five meetings through 2019. While some progress was made in returning smaller archive materials and minor assets, artistic pieces, gold inventory, and other valuable materials continue to gather dust in Moscow. (The estimated value of these goods sits at somewhere close to EUR 15 bln, not taking into account historical significance.

A great national loss

Since then, even the Council of Europe agrees that these historical items included the finest of what there was in Romania at that time, with the NBR and governmental authorities continuing to take all necessary actions for these valuable goods to return home, alongside countless incomprehensibly valuable artistic, state, or heritage pieces.

From all the declarations, meetings, documents, and books surrounding the Romanian Treasure, only Radio Romania International has encapsulated all the feelings and prospective evolutions into one sentence – “one hundred years on, the Romanian treasure is still in Moscow, a prisoner of a disloyal friendship.”