It is believed that Ján Vagač, a butcher and trader from the town of Stará Turá, often traveled to central Slovakia for business. On the way, he slept in the houses of local shepherds, who would offer him a meal of bread and soft cheese. The cheese sparkled his interest. He started experimenting and would mince it, roll it, and add salt. His efforts were fruitful, and in 1787, in Detva, Vagač founded the first bryndza manufacturing company.

It did not take long before other families came to the region and started producing and exporting the same product. Bryndza soon gained recognition in the whole of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, earning its place amongst the most well-known and well-loved Central and Eastern European foods. The families were said to be competing fiercely for the quality of bryndza, but at the same time cooperating strategically to protect it from the competition from various, low quality, so-called bryndza.

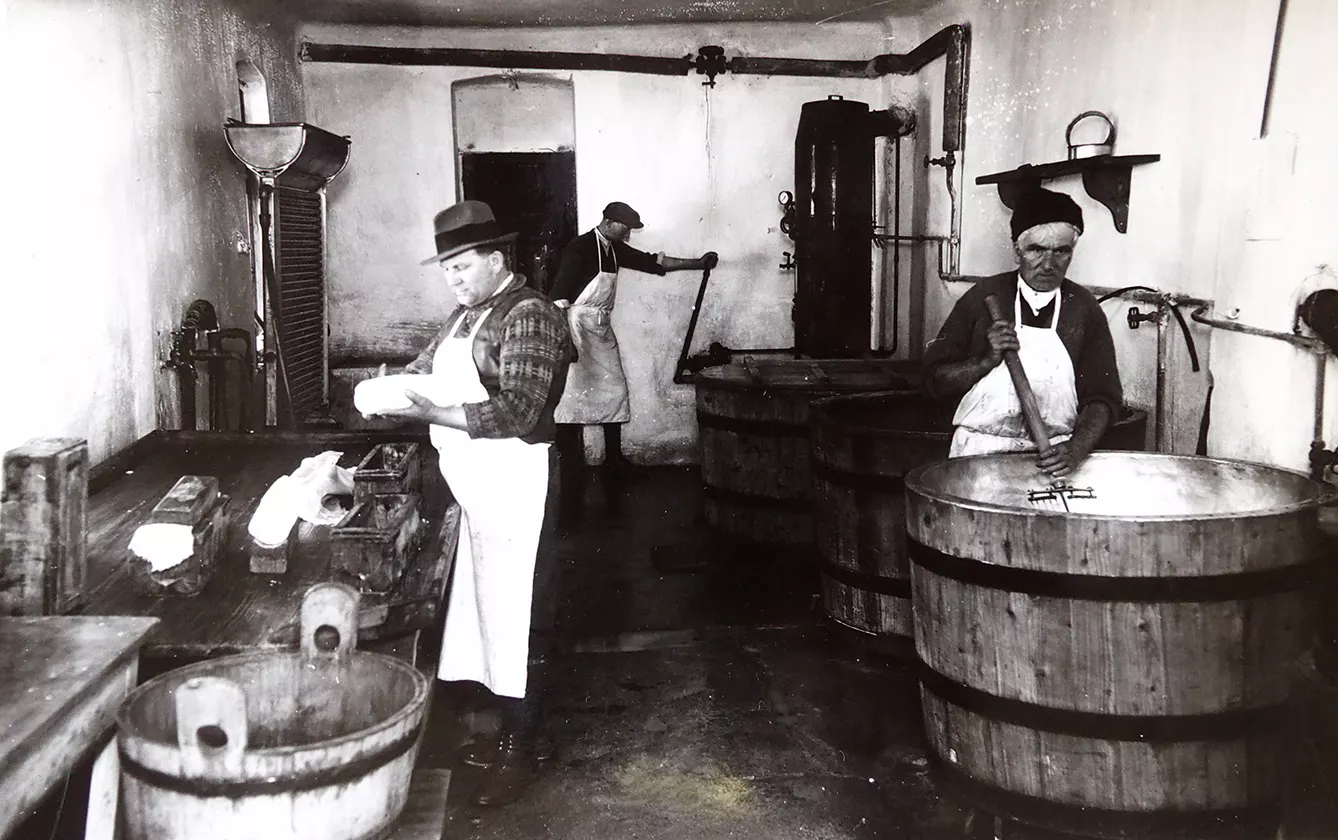

A recipe perfected over time

The recipe for bryndza has also developed over time. Teodor Wallo, the co-owner of the Detva factory, discovered that bryndza was better when the salt was diluted in liquid before adding it to the cheese. This made bryndza smooth as we know it today.

Despite the fall of the Empire, the businesses managed to keep on selling bryndza abroad, mostly in Austria. It was noted that as many as 95 wagons of bryndza entered Austria in 1918 with the factories in Podpolanie producing 60% of all bryndza in the newly created Czechoslovakia. Specifically, approximately 10% of the annual average production of bryndza, which amounted to approximately 350 tonnes, was exported abroad.

The interwar period was not without additional challenges. The taxes on bryndza were increasing, while the number of sheep was decreasing. Export to Austria was becoming increasingly difficult as other countries started selling their bryndza products on the market. Despite that, the consumption of bryndza in Austria remained high. According to Pavlov’s account, approximately 347-414 tonnes of bryndza were exported to Austria in the years 1934-1939, right until the outbreak of WWII an equivalent to 70% of total bryndza consumption in Czechoslovakia.

A changing bryndza market

The original manufacturers were becoming increasingly concerned with new bryndza emerging on the market and gathered in unions to protect their products. Some, like Štefan Vagač, went as far as engaging in local politics on behalf of the Agrarian Party, to strategically advocate for the support of small, bryndza-producing businesses.

These efforts did not last long, as shortly after the end of WWII all family-run bryndza manufacturing companies ceased to exist and never returned in their original form. The newly centralized state production, introduced by the socialist regime that came to power in 1948, was to blame for their demise.

Nonetheless, the legacy of bryndza continues to dominate Detva. The former Vagač factory is being reconstructed and transformed into a brewery combined with a museum dedicated to the family. However, the legacy of the bryndza-producing families goes much further, as they became founders of multiple local leisure and sacral monuments and facilities.

The efforts to protect bryndza were finally successful in 2008 when it was added to the Union List of Novel Food.