The student, Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, wasn’t visiting villages to help with produce, though. His task was to help farmers display whatever small amount of goods they had in an appealing way so passengers looking out the train window see the one thing lacking in these parts – prosperity. Javacheff advised farmers to keep things neat and organized to imitate affluence in front of curious foreigners on the Orient Express.

It was this young student’s desire for organization and visibility that would help him during his transformation from Bulgarian-born art student Christo Javacheff to world-famous avant-garde artist Christo – no last name, known for wrapping up anything from people to the Reichstag, while much like with his other projects, keeping it on display for everyone to see.

Born in the city of Gabrovo in Central Bulgaria on 13 June 1935, Christo was raised in a well-off, educated family that counted painters, sculptors, and artists among their friends. His journey to the West passed through Prague, where Christo briefly studied before hiding in a train headed for Vienna in 1957. “I can no longer endure. There was no point in meeting people who did not understand me, people who are selfish, who humiliate me and imagine that they understand art, which has proved impossible in Bulgaria,” he describes the reasons behind leaving Bulgaria forever in a letter to his brother.

Christo, the Westerner

After a stint in Vienna, Christo made his way to Paris in 1958. In the French capital, he made a living by drawing portraits. It was one such commission that eventually led to Christo finding the love of his life and future partner in his world-renowned projects. That special someone was his wife, Jeanne-Claude, also with no last name, born on the exact same day as Christo.

The artist was working on a portrait of Jeanne-Claude’s mother when the two met. Christo and Jeanne-Claude started working together in 1961 before moving to New York in 1964. It was New York, a new ground for both, which would become their home until their deaths, Jeanne-Claude’s in 2009 and Christo’s in May 2020.

Already in Paris, Christo’s infatuation with organizing objects resulted in The Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain, a 1961-1962 project for which the couple used oil drums to close off a narrow street in Paris, creating a kind of “iron curtain” in protest of the Berlin Wall. Set on Rue Visconti, one of Paris’ narrowest streets, the “Curtain” stayed on for only 8 hours, long enough to disrupt most of the traffic of the Paris Left Bank.

In the coming decades, as the family kept adding jaw-dropping large-scale projects to their artistic portfolio, a clear pattern emerged: the industrial use of fabrics to convey the temporary nature of the artworks. Decades in the making – most often courtesy of an unimaginable red tape – the installations of Christo and Jeanne-Claude are also known for their very short life span.

Wrapped monuments

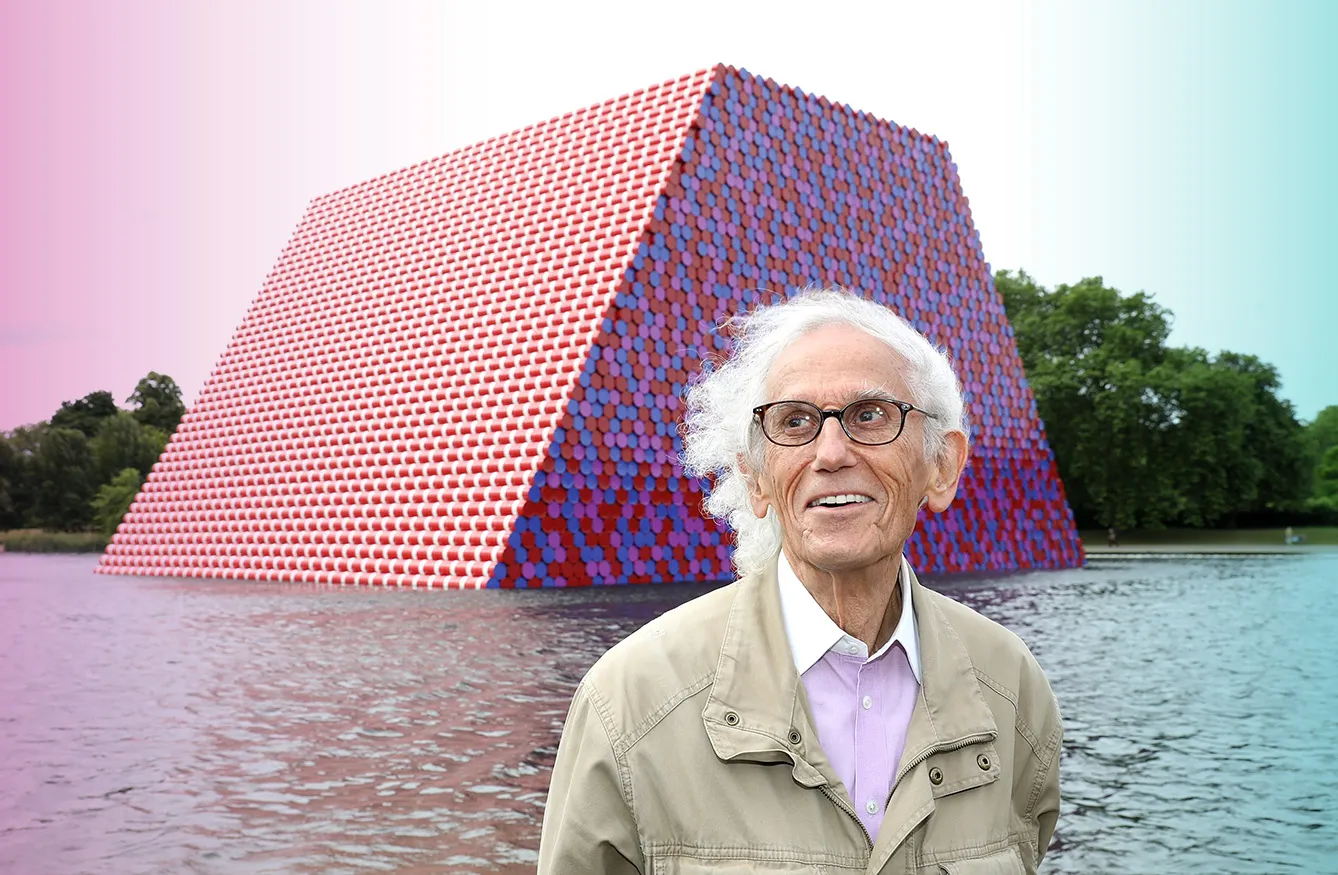

The Gates, the couple’s installation in New York’s Central Park featuring 7,503 metal frames festooned with orange fabric, took 26 years to complete, most of it buried in paperwork. The Gates opened to the public in 2005 for only 16 days, attracting some five million visitors along the way. Like all other their famous works, including Wrapped Coast near Sydney, Valley Curtain in Colorado, Running Fence in California, Surrounded Islands in Miami, The Pont Neuf Wrapped in Paris, The Umbrellas in Japan and California, The Floating Piers at Italy’s Lake Iseo, and The London Mastaba on London’s Serpentine Lake, the bill for The Gates, whooping USD 21 million, was footed entirely by the artists.

Again, just as with his initial interest in “packaging” things out of necessity, it was Christo’s experience growing up in Bulgaria under the communist regime that made him rely exclusively on himself for his work. “I came from a communist country. I use my own money and my own work and my own plans because I like to be totally free,” he once said.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude brought 28 projects to completion. Christo was selling his own drawings and models, thousands of them, to bankroll the visions he and Jeanne-Claude, the logistical mastermind behind all his big endeavors, had. According to one estimate, he sold works worth USD 66 million from 1987 to 2003.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: art with no tickets

But despite the hefty price tag, their projects were made available for all to enjoy for free. In 2014, Christo talked to the New York Times about his extraordinarily sized pieces. “They’re totally irrational and absolutely unnecessary. They cannot be bought; you can’t charge for tickets. The world can exist without them. And this carries a kind of absolute freedom,” he said.

With the artistic family regularly making headlines around the world with their work, back in Bulgaria, Christo’s country of birth, his escape to the West and his successful career weren’t discussed. “People were afraid to talk about this,” Christo’s brother Anani recalls. With art writers often mentioning Christo’s somewhat peculiar command of English, the artist was also not known for making use of his Bulgarian. Bearing painful memories of growing up in communist Bulgaria and being unable to attend the funeral of his parents, it is widely believed in Bulgaria that Christo didn’t necessarily share any warm feelings for the country of his birth.

And yet, in Gabrovo, Christo’s city of birth, another tribute to the artist and his wife, different than the occasional exhibit on the subject hosted here, is in the works. The planned Christo and Jeanne-Claude Center for Contemporary Art will occupy an existing building in the city of 60,000 residents and, once delivered, will feature an exhibition on the history of the Javacheff family. The exhibition will also follow Christo’s childhood in Gabrovo, and it will, of course, also present his works.

The Center is also planning to host exhibitions by artists influenced by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, and perhaps most importantly, it will also offer studio space to artists who, unlike Christo back in the 1950s, can now freely move and work.