Have you ever heard of Perestroika? It was a Soviet economic reform plan devised by Mikhail Gorbachev. Or was it? What if we told you that the initial idea was from Czechoslovakia? It’s true. The original idea was part of the reforming process in Czechoslovakia in 1968, widely known as the Prague Spring.

You see, Czechoslovakia became a communist country in 1948. When the initial turbulences ended, the regime fully stabilized itself in the early 1960s. By then, a new generation of reform communists had slowly come to power. Those guys felt adventurous and a bit unsatisfied with the static state of the nation. So they elected a young reformer as their leader and devised a grand experiment: socialism with a human face.

The heart of Europe, the heart of an experiment

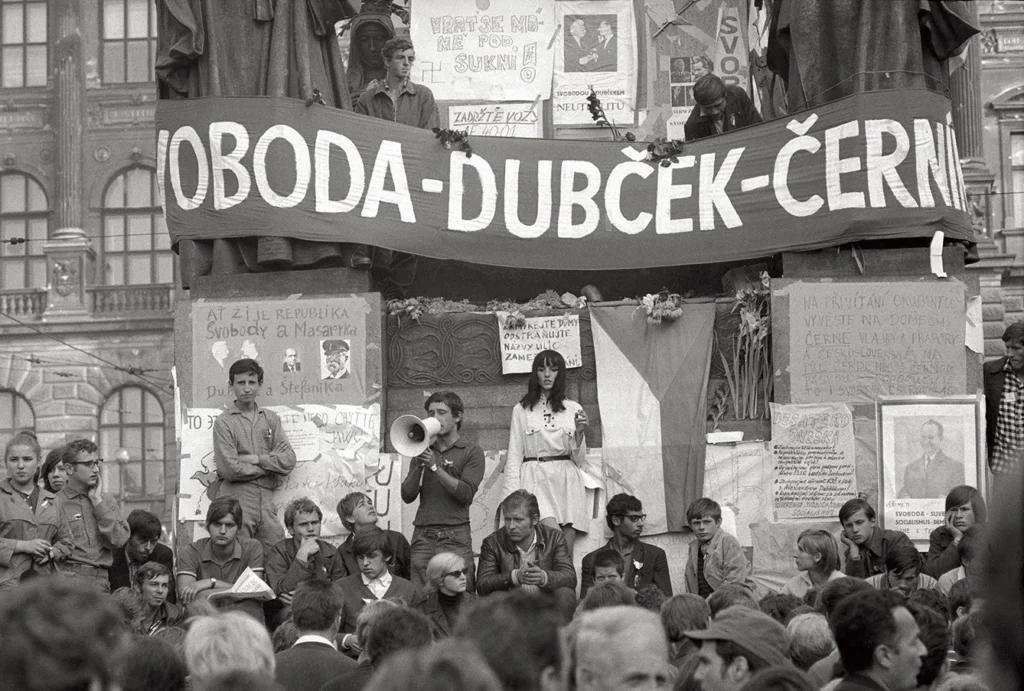

The head of this new experiment was Alexander Dubček, who the Politburo elected as a General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Since day one, he has become an architect of a new Czechoslovakia, an icon for Czechs and Slovaks who they believed would reconstruct the country.

It didn’t take long for Alexander Dubček to get to work. His project was called “Socialism with a human face”: a new socialist system that would offer people some degree of freedom, assurance, and a future, not just hard work and never-ending repression. He introduced the Action Plan of the Communist Party in February 1968, which spoke of the need for structural reform. These were to be political, economic, and social reforms. Surprisingly, the changes were quickly brought to life. Not long after Dubček’s inauguration, censorship was loosened. Another significant change was the ability to travel abroad, a luxury strictly prohibited since the communist coup in 1948.

Economic troubles

In the first half of the 1960s, the Czechoslovak economy stagnated. When Dubček became General Secretary, it was already in an economic crisis. Dubček himself said during the Action Plan introduction: “We must stop talking only about improving the system and make it clear that we are in dire need of a profound economic reform that aims to create a new functioning economy.”

The head of this economic reform was Czech Economist Ota Šik, who would propose a complete overhaul of the economy. Professor Šik outlined a precise plan to slowly liberalize the markets and allow Czechoslovakia to start a new economic chapter with less government control. Dubček liked it; conservative communists and Stalinists did not.

After spring came winter

These hardline communists, who had watched the Prague Spring from afar, began to dread Dubček’s and Šik’s loose policies and their reform attempts. Some regularly reported the situation in Czechoslovakia to Moscow, while others called for active Soviet intervention.

The reports of conservative communists alerted the Soviet Politburo. The Soviets reached out to Dubček and were clear: “Reforms must end, or the reformers will end.”

Frightened by soviet threats, Dubček addressed the nation and said that the reforms would have to be slowed down and rethought. But it was too late. By the time the Soviets threatened Dubček, it was already decided: both the reforms and reformers would end.

On August 20, 1968, over 400,000 Warsaw Pact soldiers invaded Czechoslovakia and forcefully ended the reforms. The Prague Spring was over. Dubček was called to Moscow, where he was told they had lost patience with his loose leadership and that the communist hardliners would replace his liberal cabinet.

Cruel winter and new spring

It took a few hours to destroy a dream of at least a little freedom. A few hours during which, allied nations invaded Czechoslovakia, killing 137 and injuring 500. Crushing censorship, out-of-control secret police, and screening committees would choke Czechoslovakia until the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

But many reforms devised by Dubček and Šik were eventually enacted and used. Unfortunately, not in Czechoslovakia, but in the Soviet Union. When the dream of reform was crushed in Prague, all the materials were confiscated and transported to Moscow for a closer examination. Twenty years later, young General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev would re-discover the Czech reform plans in Soviet archives, bringing them to life as his own Perestroika.