Perhaps it does not come as a surprise that the Wikipedia article covering Rubik’s Cube is by far more extensive than the one about its creator, Hungarian architect Ernő Rubik. It includes topics such as the 1980s Cube craze and its 21st-century revival as a digital challenge. It describes millions of combinations to solve the puzzle and potential strategies. Eventually, it also describes how the toy, formerly known as the Magic Cube, influenced both culture and science.

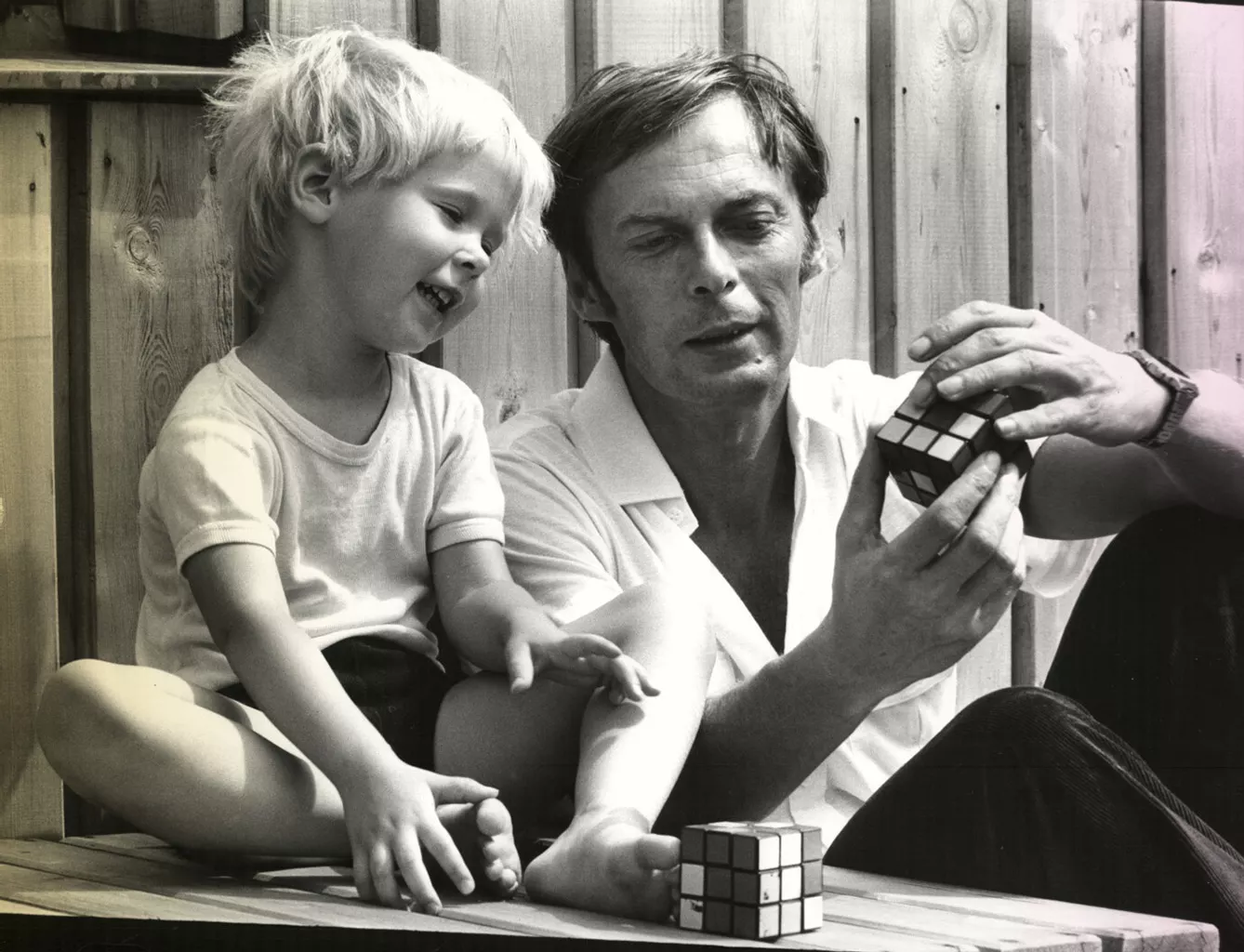

The iconic puzzle’s millions of potential combinations also reflect the personality of its inventor Ernő Rubik Jr. Born in 1944, Rubik still is somewhat of a cult figure in the gaming world as well as a propagator of STEM education policy to promote interest in science and problem-solving among young people across the world.

Ernő Rubik: the perfect (genetic) combination

A citizen of Budapest for his whole life, Rubik is the son of an aircraft design engineer and a poet – which makes sense, as his main invention combines the quest for mathematical formulae within an open form, creating a vast array of possibilities from just six colors and 54 squares – just as the perfect combination of a few simple words can create poetry.

Rubik graduated from both the Secondary School of Fine and Applied Arts and Budapest University of Technology. He later also took a university-level course in Art. This combination of degrees set him on the path to architecture – the craft of combining beauty and engineering. However, his work as an architect lasted only a few years, as in 1974, he designed his masterpiece – the Rubik’s Cube, which soon puzzled and took over the world.

Rubik’s Cube: the toy that became a cultural icon

The toy does not need an introduction nor a detailed description, as everyone knows its cubed shape and squared design. In the unlikely circumstance that someone doesn’t have a clue – just one glance would suffice to know what was the game’s objective: to arrange the colors neatly, providing your mind with the instant gratification of seeing things put in the right order.

But, easy as it sounds, Rubik’s Cube allows some 43 quintillion permutations. (*One could expect as much from a Hungarian: they seem to love big numbers just as much as they like their “ő”. Their highest value note in history was worth one hundred million billion pengő).

In the following years, the Cube sparked a craze. Variants as large as 17x17x17 (instead of traditional 3x3x3) appeared, and its initial cubic form mutated into many more (as did the dice in the times of Dungeons and Dragons). The Guinness World of Records covers not only the fastest solution to a scrambled Rubik’s cube (under four seconds in 2018) but also others in the category, such as the largest cube (apparently, the verification is still pending for a 33x33x33 variant). Compulsive Rubik’s Cube solving has even become the international pop-culture symbol of a tormented mathematical genius.

Success that is hard to replicate

Other lesser-known puzzles by Rubik include the Snake and Square One. They had their fair share of popularity but, obviously, never reproduced the success of Rubik’s Cube. On the contrary, Ernő Rubik remains popular among the Cube’s die-hard fans. An introvert who is not a fan of making public appearances, he uses his recognition and material resources through the International Rubik Foundation to promote game design and to encourage young people to study according to STEM principles.

Founded by Rubik, his Rubik Stúdió calls itself a Creative Disruption Agency. It creates branding, user experience, and marketing solutions. One could say that this area of expertise is the opposite of puzzle challenges, but disruption is what the Rubik’s Cube was when it first appeared in the 1970s.