The increasing omnipresence of American-imported Halloween traditions in Central Europe has come with conservative critiques: it’s anti-Christian, commercial, and not rooted in regional traditions. But is it?

Church teachings aside, the roots of Halloween might not hail directly from Central Europe, but that doesn’t mean they’re not close to an almost identical long-lost local celebration. While Halloween is based on Samhain, the Celtic harvest feast when boundaries between natural and supernatural are blurred, this annual event had a Central Eastern equivalent in the form of Forefathers’ Eve (in Polish: Dziady).

Dziady, the Slavic Halloween

Northern Slavic culture – currently consisting of Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and to some extent Lithuania, a Baltic country that for centuries shared a large part of its culture with Poland, called the custom “Dziady” or some other form of the word. The word has various versions and meanings referring to old men: the elderly, grandfathers, and old beggars (technically, retirees in the then-retirement-less society). In the case of this holiday, it meant dead ancestors, and “Dziady” was a way to communicate with the latter.

So yes, ghosts were involved. And spirits. And all the mystical paraphernalia, including lighting fires, talking to the dead, dedicated rituals, and even dining with the dead (kind of a trick-or-treat). As the date was fixed, starting at sundown on November 1st and going through sundown the next day, and as most people had someone to talk to, this was also, to some extent, a social event. After all, it takes a village to raise a ghost.

How do we know all that about past customs, you ask? Well, one thing is to look at how neatly it merged with Christianity. It’s quite clear that all of these kinds of events share some symbolic basis. In this case, autumn days get shorter, day surrenders to night, and plants go dormant – it’s all a form of cyclical dying in the expectation to resurrect. The night is the time of the uncanny – such as ghosts talking to people.

For centuries, the Church was hesitant to fight pagan customs or implement the rule that if you can’t beat them – join them. Finally, it appears the church tried an all-in-one solution, converting Forefathers’ Eve – “dziady” – into “zaduszki,” or All Souls’ Day. This is observed the day after All Saints’ Day and is dedicated to the dearly departed.

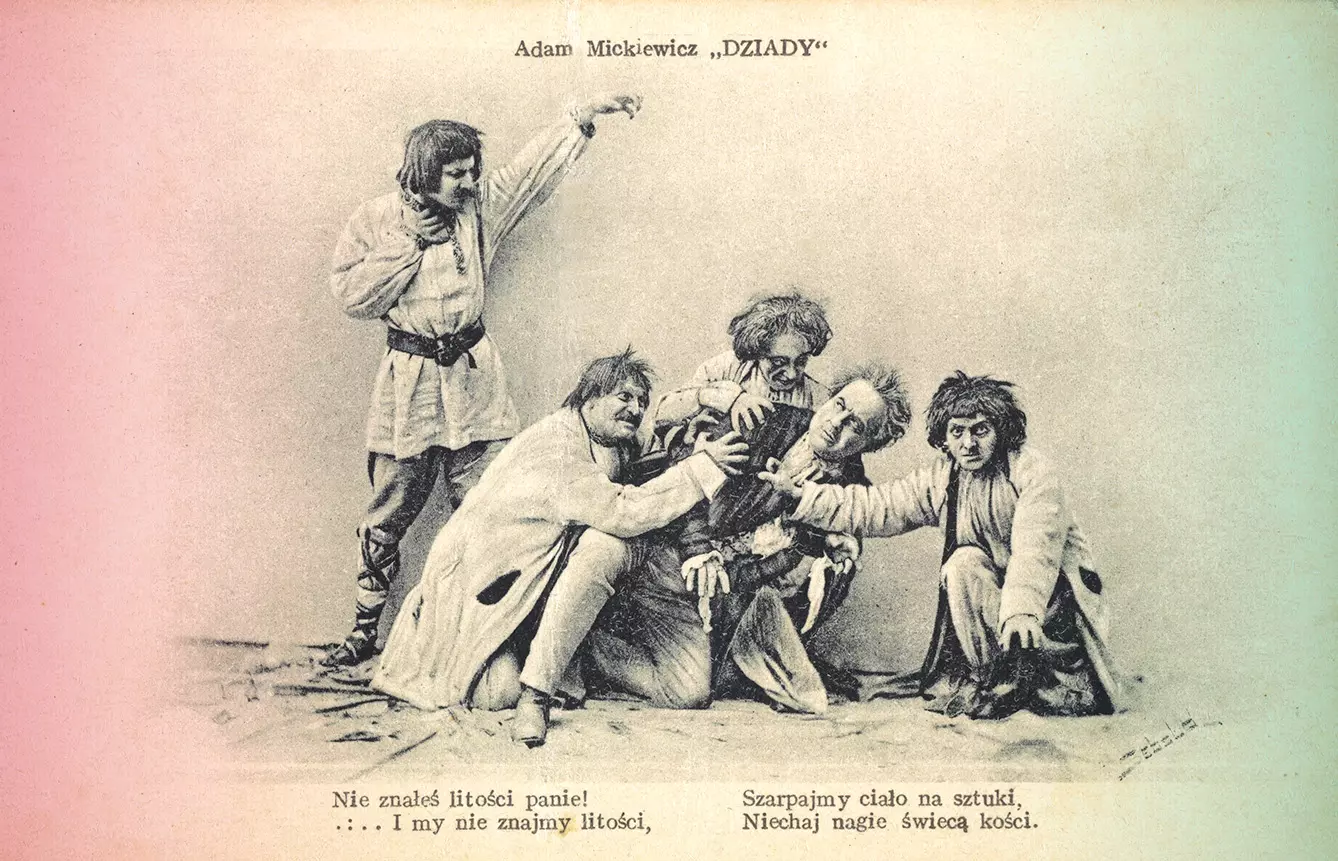

Adam Mickiewicz and his “Forefathers’ Eve”

But the tradition is also very well described, most famously in the Romantic work “Dziady” by Adam Mickiewicz. This work, written by perhaps the most important poet of Polish Romanticism, was technically Lithuanian. During the time of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the cultural difference was relatively small. It’s a fact that Mickiewicz’s most famous phrase, written in Polish, is “Oh Lithuania, my fatherland!”.

Lithuania was the last country in Central European Christendom to convert and only did so in the 15th century. Even now, it has a distinct lean toward paganism. In its merger with Poland, perhaps it’s fair to say that a share of the pagan ritual was transported through it to the common northern Slavic culture.

And Mickiewicz’s experience, his typical Romantic appreciative approach to folk culture, made him a particularly astute observer – and narrator – of rituals such as Forefathers’ Eve. “Dziady” – the title of his play, not a custom, was perhaps based on these experiences. A three-part series touching on, for the most part, mystic visions of political prisoners fighting against the Russian regime or the hauntology of the Polish past.

But in one part, called “The Second” (Ironically written first a là Star Wars – though the prequel was never finished), the proper ritual of Dziady happens. The leader of the ritual – Guślarz – summons the spirits of those who, after their death, were unable to loosen their earthly bounds. Three spirits appear – all people from the village.

The Forefather’s Eve souls relieved

The first to appear are the children. They died too young to know the bitterness of life and hence cannot expect the sweetness of salvation. However, there was a solution and hence salvation for them – a few mustard seeds to add bitterness to their not so out-of-this-world existence.

Second, comes the feudal master. He’s kind of the equivalent of a slave owner, brutal during his earthly life. He doesn’t ask for salvation; rather, he is hoping for actual damnation instead of facing the dread of being held in unending purgatory. He is treated with food, but all of it is stolen by the birds. Ironically, he gets what he asks for in eternal damnation, however, his damnation takes the form of infinite purgatory.

A third guest – a young, romantic girl – follows a similar pattern. She was always flirting, never loving, always indulging in poetry and singing; she never touched the earth – and, thus, cannot enter heaven. For her are two more years of this earthly purgatory before she eventually reaches heaven.

So is Forefathers’ Eve the Central European Halloween? Yes, it isn’t. Everything is there: scary stories with educational parts, social events, ghosts next door, and even treats. It’s just a parallel universe of Slavic and Baltic supernatural creatures rather than Celtic ones. Perhaps, these are the spirits we are all yearning for. And perhaps there’s a common root in all these All Souls’ Days, thousands of years in humanity’s past.