For a long time, the countries of far Asia were treated as the factory of the world. Since the last decade of the 20th century, words like “outsourcing,” “offshoring,” “decarbonizing the economy,” and “optimizing production costs” have been repeated like a mantra. “Outsourcing is another form of trade that benefits the U.S. economy by giving us cheaper ways to do things,” said Janet Yellen in 2004 when she was the chief economist of President Clinton’s administration. This goal was to be met by relocating production to the Far East. Western countries were to develop services; manufacturing plants were to be the domain of Asian developing countries. This is what “the end of history” was to look like from the economic side.

But the history is not over. The recent Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have shown that the world is changing constantly. It has emerged that Asian countries have become leaders in industrial production – including in the most high-tech areas. Over the past two decades, the West (mainly Europe) has lost its leadership role in high-tech manufacturing, specifically for digital technologies. Only recently have there been attempts to reverse this.

Central European countries have been playing their part in this, increasingly attracting high-tech investors. It has a lot to fight for – because by opening up widely to investors, it has the chance to win a large share of the high-tech pie and thus strengthen the region and the EU as a whole. There is no doubt that this is where the battle for dominance in the modern world will be decided in the coming decades.

Over and over again

“Europe now accounts for almost a quarter of global R&D and GDP, but only 10% of emerging technologies. This sector is dominated by the Americans and the Chinese, from the internet giants to the champions of artificial intelligence and biotechnologies. This imbalance is occurring at the start of a new industrial revolution, which will bring huge productivity gains,” wrote Prof. Philippe Tibi, an economist from Ecole Polytechnique in Paris and an adviser to the French government. He believes that Europe’s weakness in this field not only means a threat to the future of the continent’s economy but also poses a geopolitical challenge – because a lack of technological sovereignty can threaten the sovereignty of European states.

Data from OECD confirm these comments. On average, EU countries spent 2.2% of their GDP on research and development (R&D) in 2021. Ten years earlier, it was 1.9%. But at the same time, the expenditure of the United States during these years increased from 2.8% of GDP in 2011 to 3.5%. South Korea’s expenditure increased from 3.6% in 2011 to 4.9% ten years later. And China increased its spending from 1.8% in 2011 to 2.6% in 2021—clear evidence of which countries prioritize R&D spending.

In theory, it should look different. In 2000, the EU adopted a target of 3% of GDP spent on R&D by 2010. It is now 2023, and this level – calculated as an EU average, including most countries from Central Europe – has never been reached; only individual countries have managed to gain it. But even then, according to Eurostat, only Sweden, Austria, Belgium, and Germany surpassed 3% of GDP spent on R&D in 2021. Most countries had problems with reaching the level of 2%.

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results,” once said Albert Einstein. EU leaders have been constantly complaining about the low level of innovation in the European economy, but at the same time, they have been doing the same thing over and over again – not spending enough on R&D. It is difficult to create an innovative economy on the continent without proper investments.

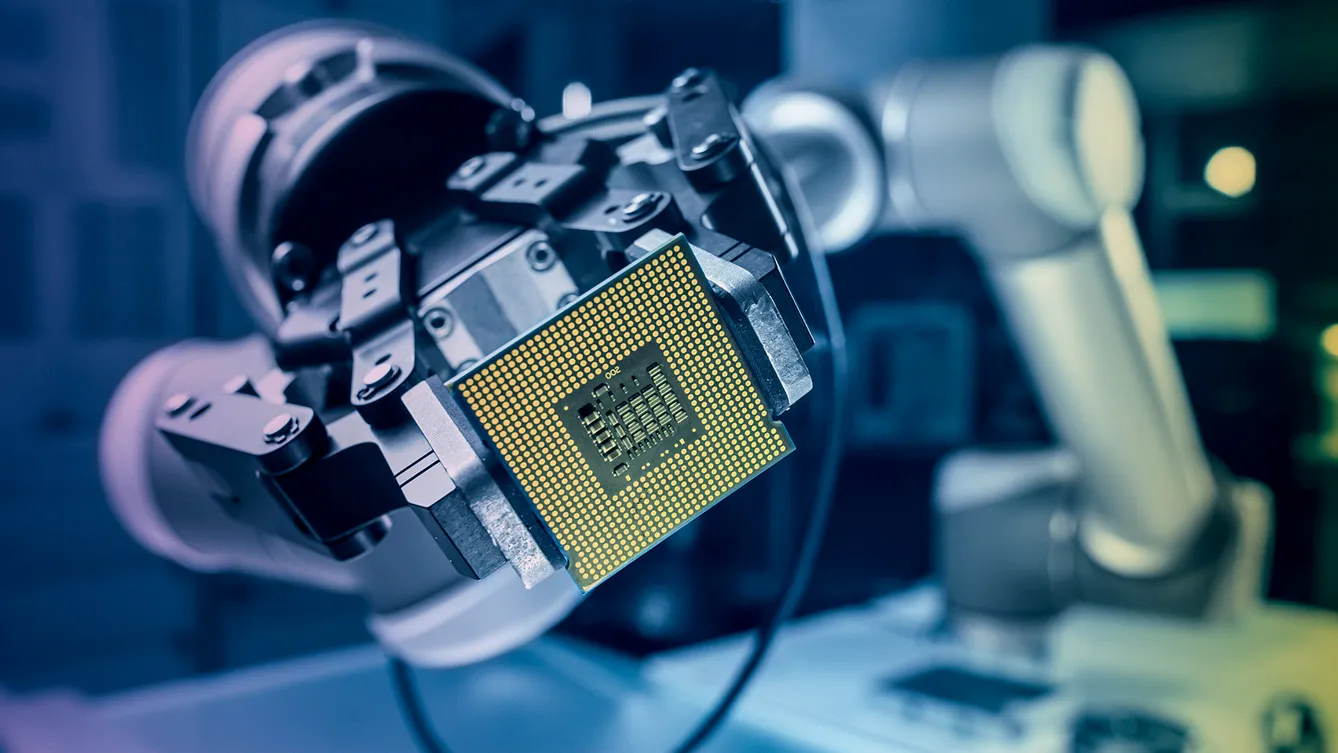

Improving the semiconductor balance sheet

This problem has also affected Central European countries over the years, where (with the exception of Austria) R&D issues have been on the sidelines for a very long time. “Innovation needs a lot of funding. This is where the countries of Central Europe are still lagging behind,” said Jürgen Rigterink, vice president of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

But a change has been evident in this area for some time, with innovation investments increasing in most Three Seas Initiative countries. This can be seen when historical data is compared from OECD. In 2011 Austria committed 2.66% of its GDP to R&D, and in 2021, it was 3.18%. The Czech Republic has spent 1.54% of its GDP on R&D – ten years later, the share had risen to 1.99%. Hungary jumped from 1.17% to 1.64% at the same time. Poland – from 0.75% to 1.43%. Lithuania – from 0.90% to 1.10%. It is difficult to call this progress ground-breaking. The region’s countries are constantly operating with small amounts of money for innovation compared to the biggest players in this market. But a trend is also emerging, with more countries in Central Europe becoming aware that their level of innovation will determine their future. Hence the increasing level of spending on them.

For Central Europe, there are other ways to operate in the innovation market besides just R&D spending. Another is to attract investors in this area. Cheap land, relatively low (compared to Western Europe) costs, and skilled workers make the region an attractive area for investors. And even the war in CEE’s neighboring Ukraine is not an obstacle to further investments.

The latest example is Intel’s investment in Poland. The U.S. chipmaker decided to invest up to USD 4.6 billion in a semiconductor facility close to Wroclaw in the western part of the country. This high-tech plant will become essential in reducing European dependence on Asian producers of semiconductors. Currently, factories in the Indo-Pacific region are responsible for over 70% of the global production of chips. Surely Europe will not be able to improve its position in high-tech development without improving this balance sheet.

Phoenix economies

Other CEE countries are also trying to contribute to redressing this imbalance. Czechia has invested a lot of political capital in building a strong relationship with Taiwan – and hopes this will pay off for it in the form of investment in the high-tech sector. In response, Taiwan’s government promised to invest at least $33 million in advanced technologies. However, it is not clear in what exact areas this money will flow.

Czechia is pushing for the creation of chip research centers in the country – perhaps fitting given that Taiwan is one of the biggest semiconductor producers in the world. However, there is still no answer from Taiwan on that field. Negotiations are still ongoing.

Lithuania has adopted a similar strategy. Here, the government in Taipei has also promised investments in modern technology – although it has not specified in which specific area these will take place. Progress is happening, as evidenced by a Taiwanese fund investing in the Lithuanian start-up Litilit, which is developing industrial femtosecond lasers used in semiconductors and other high-tech industries.

Romania and Bulgaria are developing high-tech projects linked with renewable energy sources. Czech-based Rezolv Energy company invested in a solar power plant in northeastern Bulgaria. By 2025 it wants to build a 229 MW solar factory on the site of the decommissioned Silistra airport.

An even bigger solar power plant is planned by the German company Profine Energy. The firm is ready to invest up to EUR 1 billion in new solar projects in this country. One of them will be a floating solar power factory with a capacity of 500 MW to 1.5 GW. This giant photovoltaic facility will be built on the Ogosta reservoir next to Montana City in the country’s northwestern region. When finished, it will be the biggest solar plant in Europe.

Similar projects are under construction in Romania. Rezolv Energy has been preparing to start the building of a 1.04 GW photovoltaic factory and a 500 MW storage unit. Total cost? EUR 1 billion. The project should be finished by the end of 2024. This Romanian energy storage unit would become the biggest facility of its kind in Europe – five times bigger than the present record holder, which is in Belgium.

The most recent example demonstrating openness to innovation came from Hungary, where the Bosch Rexroth Innovation Experience Center was created in June 2023 in Budapest to foster the exchange of ideas on the future of industrial technology, especially in the field of digitalization. The earlier Hungarian government decided to create The Research Center for Autonomous Road Vehicles – the initiative that helps develop technologies that allow driving without the driver. Hungary has also attracted an investor from China, which decided to spend EUR 7.34 billion on a battery plant. When built, it will become Europe’s largest battery cell plant.

Performing above expectations

Traditionally, Estonia has been the most advanced country in the development of modern technology. From Three Seas Initiative countries, only this country and Austria were put on the list of states performing above expectations for the level of their development by the Global Innovation Index in 2022 (in contrast, Lithuania and Slovakia were among the developing countries below their potential). In 2023 alone, Estonia attracted Ericsson, which decided to invest USD 169 million in smart manufacturing and technology hubs that will be constructed in Tallinn. Thanks to its appealing tax policy, Estonia has also been attracting people from the IT sector from the whole world – thus becoming one of the leading tech hotspots.

“It was fashionable to call the Central European economies “tiger economies.” The tiger was severely wounded by the crisis, but the way it has overcome the challenges has demonstrated the country’s resilience. Today, it may be time to talk about the “phoenix economies.” They have risen again. In order to fly, they need nothing more than innovation,” said Jürgen Rigterink from EBRD.