Well, the answer may be tricky in all its simplicity: weaponized deportation, even still a common tactic Russia uses to wage war, was already in use back in the 19th century. One of Russia’s boldest steps in its current war in Ukraine, and, as it seems, the most overshoot one, was to declare the annexation of a few Ukrainian regions based on sham referenda supposedly conducted in each of them.

Though the result was scary – a further escalation of the conflict – some actually found it funny. After all, Russia declared the annexation of territories it didn’t control. The first to mock the move were the Czechs, who claimed the annexation of the Russian Kaliningrad region based on the fact that it was named after, and technically established by, the Czech king during the Teutonic Crusades against pagan Prussia.

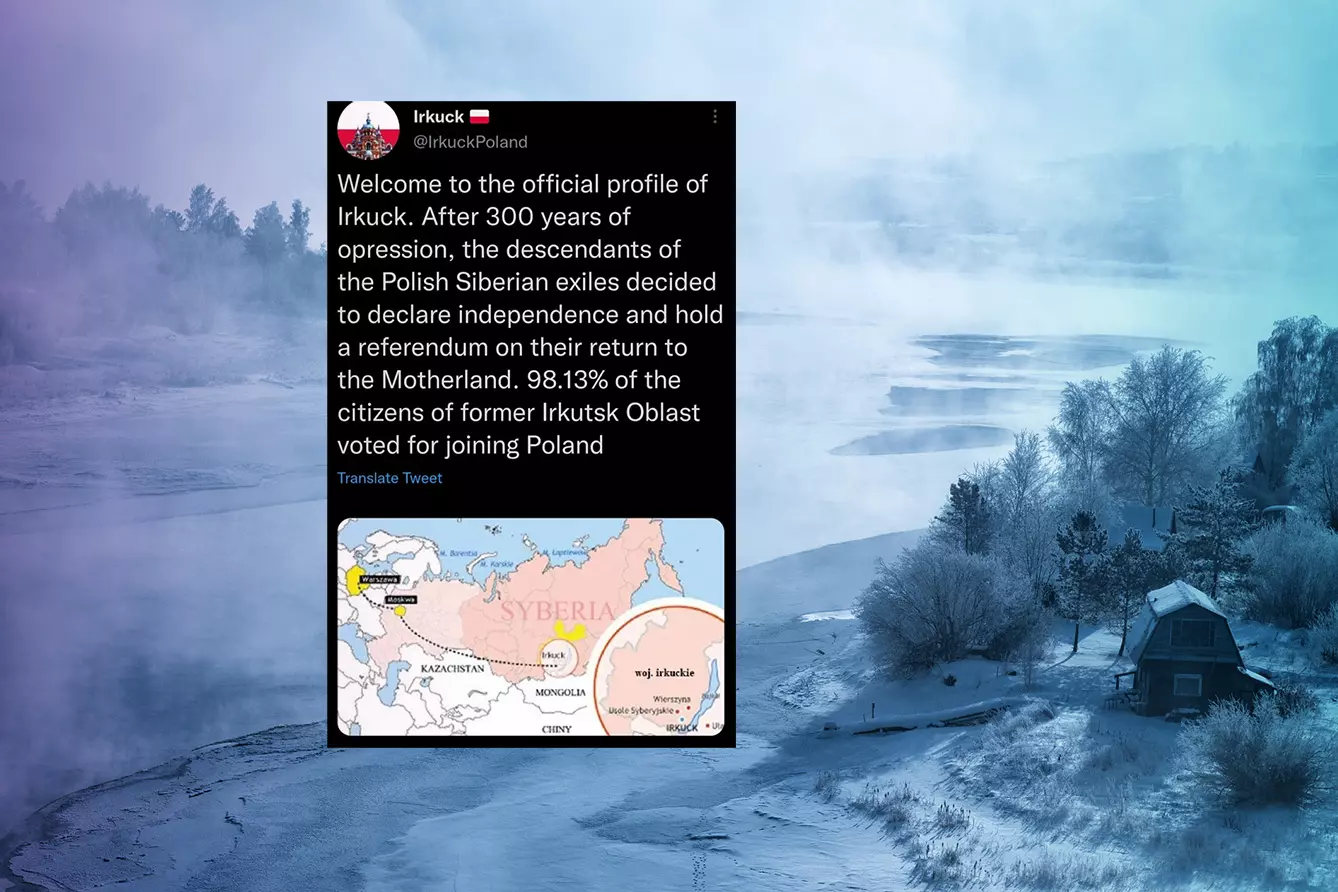

But Poles wanted to catch up on their neighbors’ joke and soon invented one more unlikely Russian region that they could “rightfully” (by Russian standards) claim as their own. And it is located far deeper into Russia than Kaliningrad (aka Kralovec). It was the Russian far east city of Irkutsk, an unlikely location for a Polish diaspora.

Poles in Siberia: a long and complicated history

To explain the presence of the Polish minority in Siberia is to run through some 250 years of Polish history and relations with its huge neighbor. In a kind of zero-sum game, the 18th century was a period when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (a country of multiple ethnicities with a shared culture based on the Polish language) weakened. At the same time, those around it – Prussia, Austria, and Russia – rose to power. Soon citizens of the Commonwealth, heirs to a centuries-old regional power, found themselves fighting for mere independence from its rising rivals.

Although technically the whole territory of Poland-Lithuania (as well as its statehood) didn’t fall to its conquerors until 1795, perhaps the first chapter of the fight for independence was the Bar Confederation of 1768 against Russian influence, coupled with King Stanislaw August Poniatowski’s efforts to navigate through contradicting interests. Captured fighters were not technically POWs, so they could be prosecuted as mutineers.

This fitted Russian politics of eastward exploration – in terms of science, military, and colonization, the vast, empty wastelands of Siberia were fit for prisoners’ settlement – no need to build prisons, as there is nowhere to run anyway. (*See also: Australia, established as a penal colony around the same time.)

A nation divided

The loss in 18th-century wars made most of Poland technically the westernmost part of the Russian Empire from 1795 through the end of World War One in 1918. These 123 years are known in Poland as “zabory” (“The Partitions”). Poland was split into three parts one controlled by Germany, one by Austria, and the largest by Russia, which continued to develop separately.

Poles never got used to their political loss to Russia. If you take a look at Polish history from the nation-forming epoch of the 19th century, it’s marked by efforts to loosen ties and finally gain independence. From the lost war in the 1790s until World War One, every generation of Poles staged an uprising.

- The first was led by Tadeusz Kościuszko in 1794 – after its failure, Kościuszko went to the then-forming United States, becoming one of the most important military heroes of the time.

- Then there were Napoleonic Wars, where there was a Polish (as the French-dependent Duchy of Warsaw) contribution – especially to the campaign against Russia in 1812. On a separate note, the Polish alliance with France resulted in a somewhat surprising Polish military presence in Haiti. However, even under Napoleon, the Poles lost.

- Later, a period of “regular” uprisings began starting with the November Uprising of 1830.

- The Cracow Uprising failed to launch in the revolutionary year of 1848 (similar to what was happening all across Europe) and turned into a social revolt instead. Still, the anti-Russian violence was there.

- The next generation had the January Uprising of 1864, with months of both military and political struggle.

- Superstitious as they are, Russians braced themselves for another uprising in 1890. Finally, it took the form of the Social Revolt of 1905, which took place across the Russian Empire.

- The final part was when preparedness met opportunity in 1914-1918, with Polish military activity and a political offensive.

Each failed uprising provided yet another “batch” of Polish non-POWs to be deported to Siberia. In 1847, Russia reformed its penal law to normalize relocation to Siberia as common practice. And it was no regular deportation – the penalty included penal labor (chopping frozen timber is one example). Hence the name “katorga,” a description for this kind of sentence derived from the word “kat,” or executioner. The sentence would usually include several years of “katorga” and then further decades of “regular” Siberian settlement.

Myths and stories of Poles in Siberia

With that in mind, the Polish culture clearly contains myths and stories of both fighting for the nation (against the same ol’ enemy for centuries now) and being punished, especially in terms of this relocation (in Polish, “zsyłka”). Siberia even gained two variants of its name in Polish: Syberia or Sybir, being so commonly used (especially given that romantic poetry needed more words for rhyming.)

Irkutsk, the most crucial Siberian city, became the Cultural center for – among others – Polish culture. And note that most Poles imprisoned in Siberia were not criminal prisoners but political ones, recruited almost solely from amongst the nobility and intelligentsia.

The list of famous artists, scholars, and activists that, at some point, found themselves in “zsyłka” is far too long to publish it here. However, it’s nearly impossible to cover even a piece of Polish cultural history without mentioning some of them – for example, the history of Bronisław Piłsudski who, as a “Sybirak,” or Siberia prisoner, became an ethnographer of local peoples.

Weaponized deportation lasted until World War II, when the Soviet invasion merely 17 days after the German one from the West led to what is sometimes called “the fourth partition.”

Before the Ukrainian war, there were an estimated 77 thousand Poles in Russia, with minorities spread across the country. Decades and decades of forced deportation to the Russian far east led to even more descendants of 19th-century Poles in Siberia. Maybe the expected Russian failure in Ukraine, and possible de-federalization of Russia, will lead to some unexpected alliances between the former-Russian states of the East. For now, it’s just another internet meme.