When the war started, Lithuanian documentarian Mantas Kvedaravičius took his camera and went to the southern Ukrainian city of Mariupol. In 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea and organized the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk Popular Republics, Kvedaravičius documented the action in his film “Mariupolis.” Unfortunately, this scenario was to play out again in 2022 when Russian tanks and helicopters officially and openly crossed the Ukrainian border on 24 February 2023.

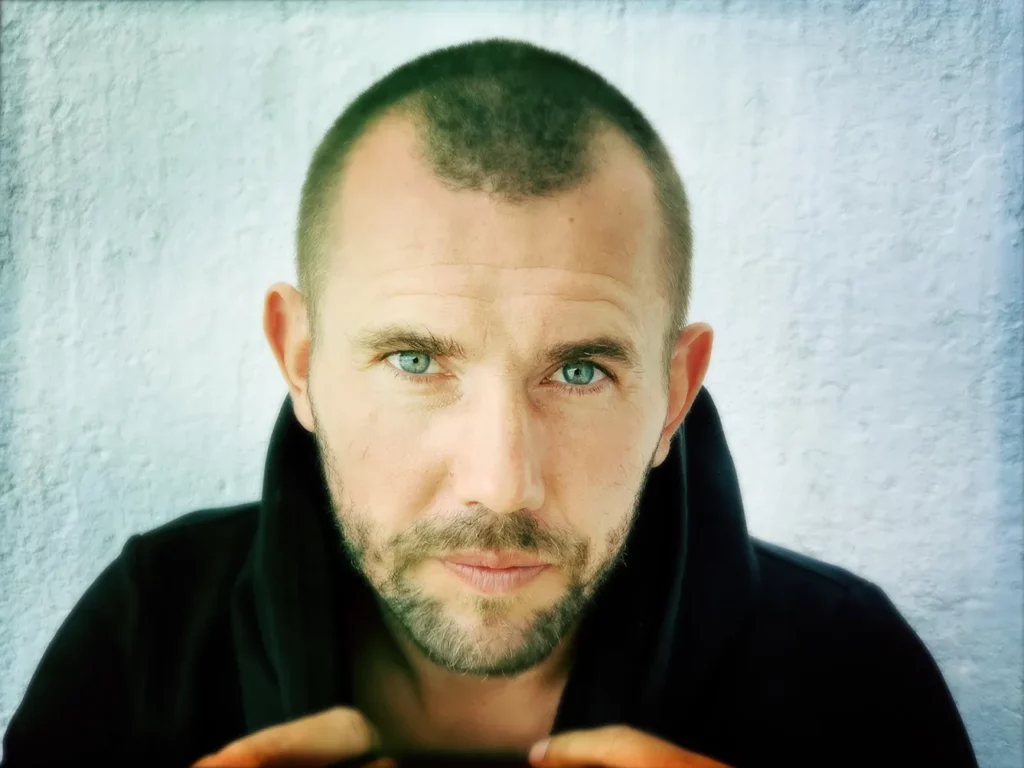

Mantas Kvedaravičius, social anthropologist and documentalist

Born in 1974, Lithuanian Kvedaravičius must have known a thing or two about so-called “russkij mir,” or The Russian Peace. He spent the early years of his life under the communist rules of the USSR, which, though officially internationalist, was a tool of Russian imperialism. Then, after the Soviet Union collapsed, Lithuania made it back to the European community. Perhaps that’s the background for Mantas Kvedaravičius’ area of expertise.

He turned this experience into a passion for exploring post-Soviet life. He graduated from the prestigious University of Cambridge, gaining a Ph.D. in social anthropology. As this study area is deeply intertwined with postcolonial relations, the Lithuanian Kvedaravičius gained more theoretical knowledge to apply to his personal understanding of the post-Soviet world.

When he turned to the art of documentary, his first movie was about Chechnya (“Barzakh,” or “Limbo,” 2011) – the same setting as his doctoral thesis. And for his second movie, he went to Mariupol, where he documented a siege by so-called separatists. The movie, released in 2016, is a record from the two previous years. Before returning to Mariupol after the full-scale invasion of 2022, Kvedaravičius made a feature movie, “Partenonas” (The Parthenon), and held the title of assistant professor at Vilnius University.

Mariupolis, One and Two

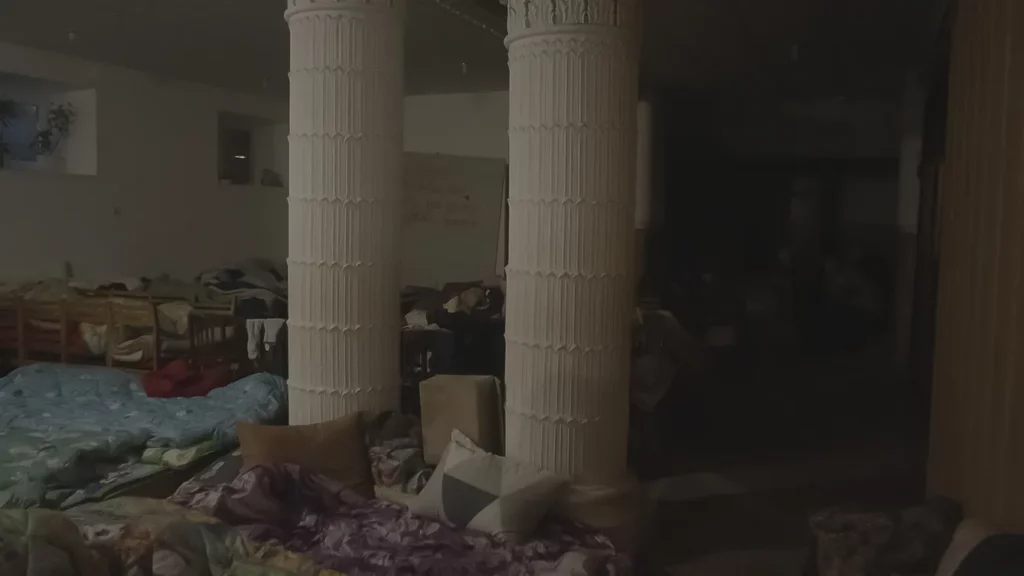

There are documentaries, and then there are documentaries. Mantas Kvedaravičius’ films are among the latter: raw, to some extent understated, presenting reality as it is, without commentary. His 2016 documentary “Mariupolis” depicts locals trying to go about their regular lives despite the circumstances. Part 2, from 2022, is set in virtually one space – the local Baptist church, where both followers of the denomination and non-believers took shelter.

Pigeons living on the ruins of a building in Mariupolis. Photos: courtesy of Studio Uljana Kim

The first film starts as the siege begins. Russian-backed separatists attacked Mariupol, which was formerly a thriving port city transporting Donetsk coal to the world, centered around the giant Azovstal Steel Factory. The separatists occupied the city for some time, even organizing a sham referendum on “independence.” Ukrainian soldiers eventually liberated the city; however, the war continued to rage nearby, and even in 2015, dozens of citizens were murdered by “separatists” with Russian artillery and under Russian commands.

Mantas Kvedaravičius’s shaking handheld camera documents the people struggling to survive under siege. There is no commentary by the filmmaker – but really, what is there to comment on? Like many documentarians, the director saw his role as a witness, limiting his interpretation of facts to the most basic – where to turn the camera and how to frame his characters. In 2014-2015, they tried to lead their lives. They took their children for walks, organized theater in a local cultural center, and commented on tanks passing by, some of them fighting for freedom.

In 2022, things were different. Most people were just busy surviving: cooking huge pots of soup, taking care of their shelled neighbors’ bodies, cleaning debris, and trying to find necessities. The camera followed them, but its moves were limited – the shelling was strong, more buildings were demolished by the day, and the simple act of walking on the street could be a death sentence.

The siege of Mariupol – recorded

Before Bakhmut became the symbol of cruel and senseless Russian aggression, it was Mariupol. While Ukrainian soldiers were flexible in outmaneuvering the Russians, the port on the Azov Sea was designed to hold, keeping Russians from establishing a land bridge between occupied lands in the east of Ukraine and Crimea.

The fight lasted for a month, with some part being a siege of the vast fortified Azovstal Steel Plant. By mid-march, less than a month after Russian aggression began, Ukrainian officials stated that not a single house in Mariupol had been left intact. The humanitarian situation was disastrous; there was no running water, energy, or phone service. The fight for Azovstal lasted until late May, but on 30 March, the city was incorporated into Russia (for now).

This was also the last day of Mantas Kvedaravičius’s life. His passion as a documentary director and devotion to exposing the truth led him to the trap of Mariupol (or, Mariupolis, as it is in Lithuanian). The movie doesn’t make it clear whether he tried to evacuate. In late March, he was captured by Russians (‘rashists,’ as they’re being described), perhaps tortured, and then shot to death. One Russian soldier led his girlfriend to his body, abandoned on the street, perhaps in an act of terror.

Supposedly, the director was captured while helping civilians – a mother and a child – evacuate. But news of his death didn’t break until the first days of April. The initial version was that he was killed by shelling, which was necessary to bring the body through the Russian-controlled border. Kvedaravičius’ body was laid to rest in Vilnius, and the film “Mariupolis 2” was released the same year.

So far, “Mariupolis 2” has been awarded the Cannes documentary prize L’Œil d’Or as well as the Prix Arte from the European Film Academy – posthumous awards he unquestionably deserves for telling the truth.