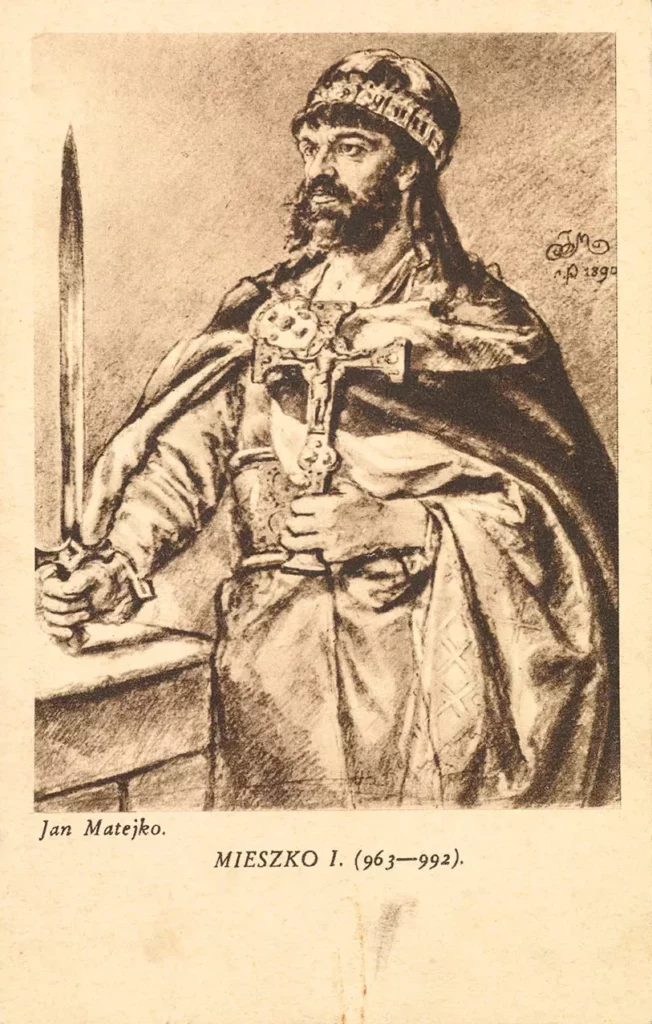

Mieszko I was the first officially recorded prince of Poland. He was born sometime in the early twenties of the tenth century and died in May 992. The lineage of his ancestors is described in later chronicles, but contrary to them – Mieszko is recorded in documents, and, well, we know he technically existed.

Under his command, Major Poland became a united country, at least according to 10th century standards, and could start its expansion. This act is now described as the unification of Polish territories. He was baptized in 966 and began Christianizing the country, following the model of Western religious practice rather than Eastern. This marked the Catholic/Orthodox border in Central Europe.

Mieszko I, the Housing Developer

The bottom line is – under Mieszko I, the northeastern Slavic tribes united into a larger body – call it a country, if you will. And it was he – the military and political leader – who led people to prosperity and served as an example forming a proto-national sentiment among folks. Well, as it was emerging more clearly, but sort of… not. And archaeology has two weapons in debunking this myth: coin treasures and gord (fortified settlements) remnants.

As far as the gords are concerned – it’s evident that wars, not great ones but rather skirmishes between tribes – were quite common. But, as some historians suggest, the settlement projects from before and during the Mieszko I epoch have three distinct periods (the last starting around 970) in which forts were being built. It somewhat resembles the ups and downs of today’s housing industry: you build things, and then the market freezes for some time.

And the similarity doesn’t end there, as it’s closely connected with money. So what currency was present in Polish territory in the 10th century? TL;DR: not Polish Zloty. That’s what buried and uncovered treasures tell us. You see, soil deposits were an extremely popular financial instrument in those days; interest wasn’t high, but it certainly was a long-term investment since we still can find coins way down in the hole.

Dirhams: Middle Eastern Coins in Polish Economy

Even today, hundreds and thousands of coins minted in the Middle East have been dug up in our part of Europe. Most of them came from Damascus. We call them dirhams (a word still used in some middle eastern countries.) There may be a little surprise to the fact that the economy of the tenth century was more global than the stereotype suggests. Though, of course, we are used to such surprises.

The real question is: what could you buy with those silver coins? One brave answer takes into account the building waves of the time, especially given that along with each building period, we find traces of other settlements from previous dwellings burnt to the ground.

It seems that good ol’ Mieszko I was not such a prince charming after all. Besides that, he likely benefited from the slave trade, exporting the most important goods of his area: people for work. (*And there’s nothing new in that notion as well, it’s enough to look at the Viking trade route from the North to the Black Sea, the so-called Route from the Varangians to the Greek).

Slavs or Slaves?

The recipients of this live cargo used to live somewhere in the Middle East. They were the representatives of the superior (at the time) Islamic civilization compared to the European cul-de-sac. Much is yet to learn about the early beginnings of Central European countries, and much more historical evidence is still buried underground. Another puzzle is the transition between this old Wild North narrative and how the early medieval well-established countries came to being.

We mustn’t forget, however, that it was during the reign of Mieszko I when the Gniezno Congress happened – the event being possibly the first geopolitical attempt at including Central Europe in the Western system. Nevertheless, the story behind the dirhams fits the stereotype of the medieval epoch: a time of great development with a rather dark lining.