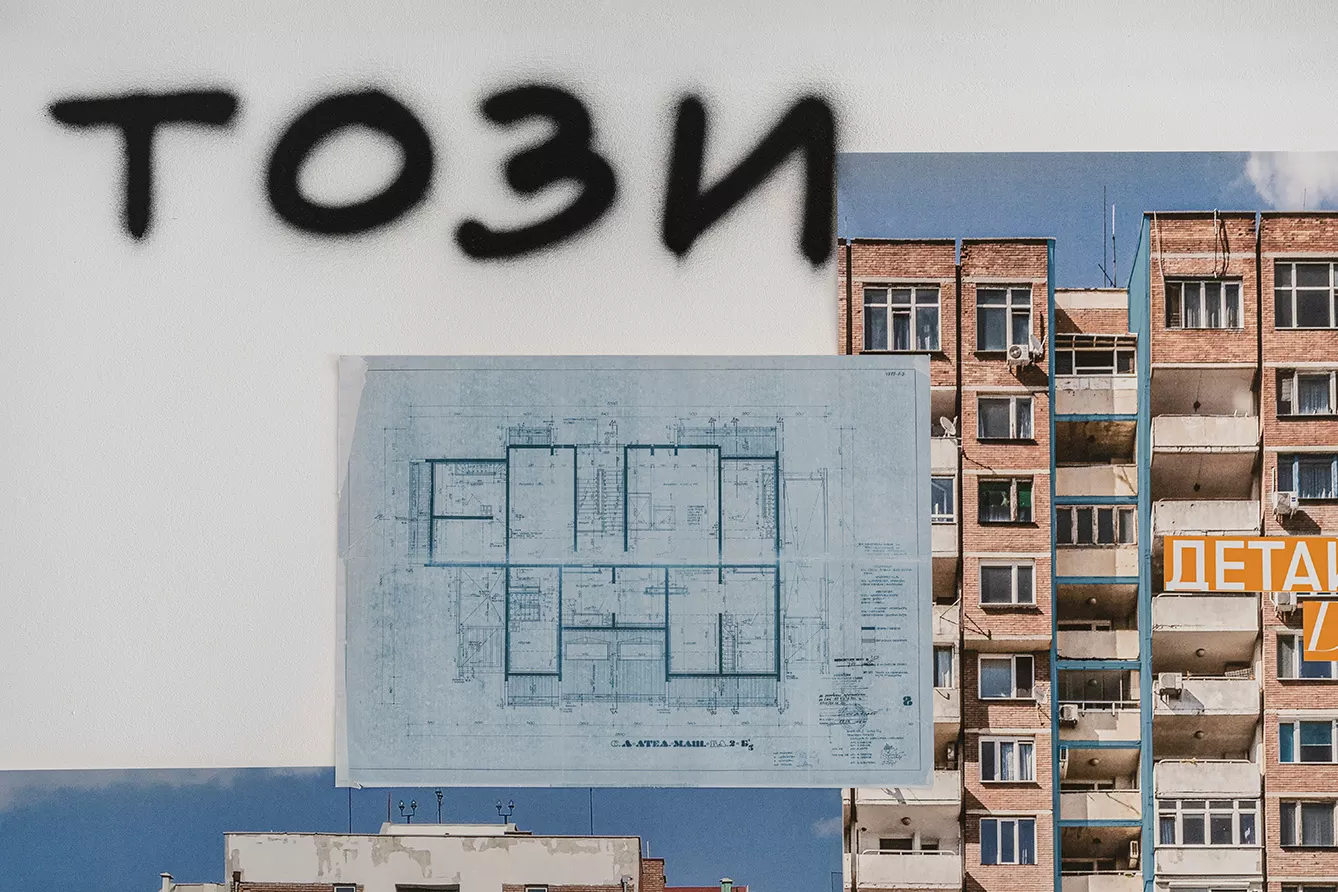

If you haven’t heard of post war architecture Bulgaria, you’re probably not alone. Bulgaria’s contributions in this area are still an obscure part of the Eastern Europe architecture of the 20th century. This legacy is largely overlooked also by Bulgarians themselves.

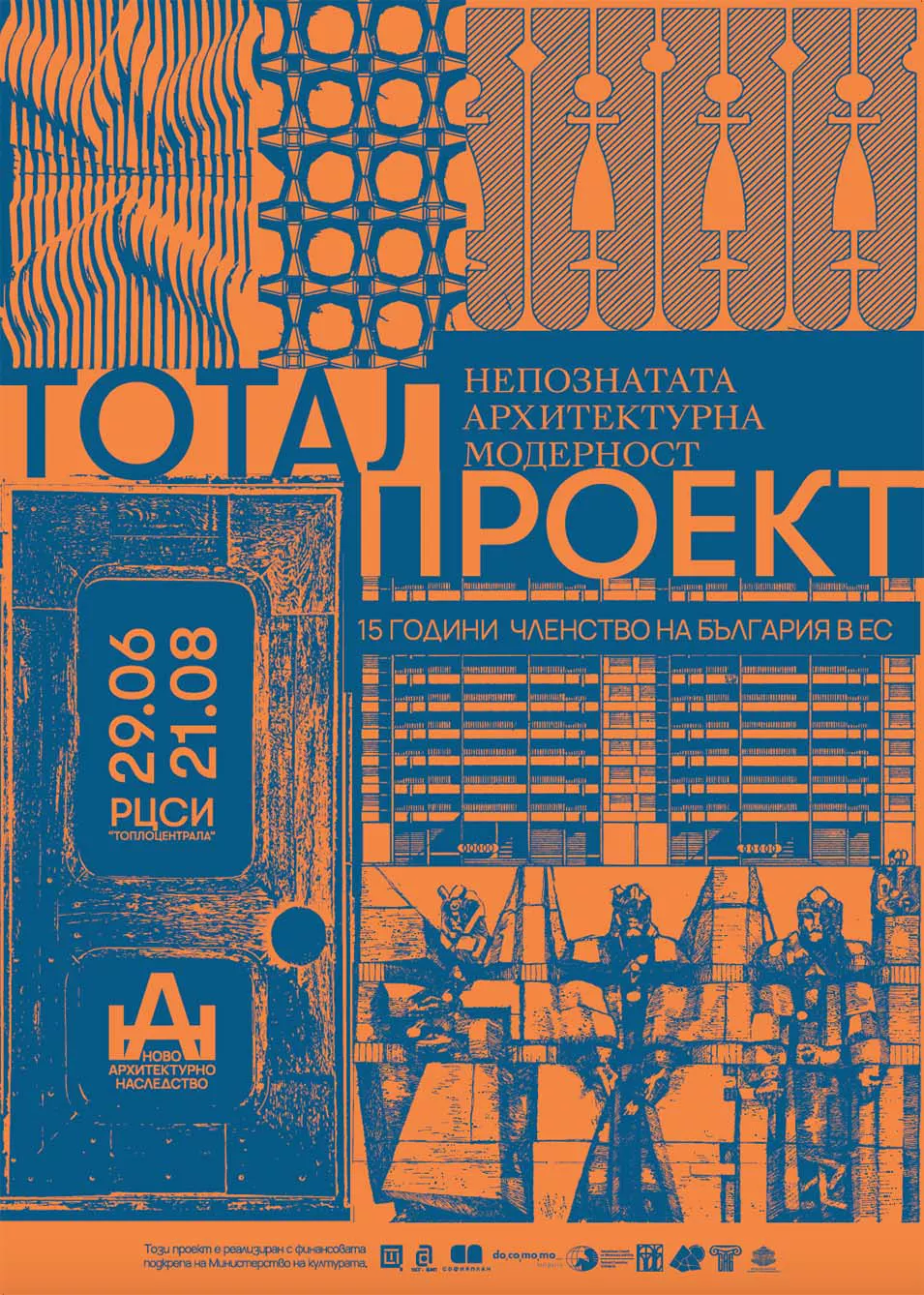

3 Seas Europe sits down with architects Aneta Vasileva and Emilia Kaleva, curators of the exhibition TOTALPROEKT. The Invisible Architecture of Modernity – a co-production of the New Architectural Heritage Foundation and Regional Centre for Contemporary Art ‘Toplocentrala’, which can be seen from 29 June till 21 August 2022 at Toplocentrala’s White Cube gallery, the newest multifunctional art space of Sofia.

3Seas: Let’s start with the basics. What’s post-war Bulgarian architecture?

Aneta Vasileva (AV): Per “post-war architecture,” we usually define this as the architectural development after World War II. In Bulgaria architecture, this period coincides with post-war reconstruction, rapid modernization, and, of course, the introduction of state socialism in our small Balkan country as a result of its falling within the Soviet sphere of influence.

We are used to viewing Bulgarian socialist architecture as a relatively closed system, isolated from foreign influences, except those from Moscow’s political center. And this is largely the case. External influences, however, did exist not only from the official “socialist” center but also from many “capitalist” sources from Western Europe, America, and Asia. They often arrived late; they were almost never applied in their pure form. However, they were undoubtedly present.

Where is Bulgaria when compared to other countries in Central and Eastern Europe architecture when it comes to debating and, most importantly, preserving this legacy?

Emilia Kaleva (EK): Bulgaria has an impressively long list of cultural heritage sites, several tens of thousands. This puts it side by side with heritage-rich European countries such as Greece and France, for example. But when it comes to post-war legacy, things are not so positive. Currently, in the National Register of listed monuments of culture, there are only four sites from this period, which is nothing compared to all the rest of the representatives from previous periods.

But steps are being taken, just like in our neighboring countries, for example, Serbia which recently protected the central part of New Belgrade as a cultural monument. In Bulgaria, the New Architectural Heritage initiative is undertaking concrete steps to identify and preserve significant architectural examples created after World War II, including residential complexes. Debate is constant, but it is mostly reserved for socialist monuments and monumental ensembles, again similar to other ex-socialist countries in the region.

Curiously enough, three of the listed post-war Bulgarian sites are namely socialist monuments. But what is missing in the National Register of Cultural Heritage is the broader context of Bulgarian post-war architecture that shaped most of the country’s contemporary environment. And we’re here to fill this gap.

Is the fact that these buildings are largely not being seen as an architectural heritage a reflection of how Bulgarians see them?

EK: The cultural value of post war architecture Bulgaria and spaces is not so obvious and is not widely and publicly accepted.

AV: But of course, again, this is valid for post-war modern architecture in general. It is not elitist, but egalitarian. Its aim is to serve everyone – to reconstruct and modernize en masse, to build its own ideal environment with a flourish. It has been claimed several times, and we repeat this as well – the 20th century is the time in which more buildings by far were constructed than during all preceding ages in human history. This is especially true for the second part of the century. And it is very easy to ignore something which is part of your everyday backdrop. It is not a castle on a hill; it is your kindergarten. It is not a Renaissance palazzo but your block of flats, your school, the factory where your grandfather worked.

Is the issue that they are simply not old enough to be appreciated?

AV: All of these museums and galleries, housing estates and public buildings, schools, kindergartens, hotels and squares, theatres and libraries are everywhere around us; they are always inhabited and are still somewhat detached from the patina that ‘true’ heritage has acquired. This is why with them being ‘more recent, they are not recognized as potentially of significance. Therefore, lately, they are too easily and too often under threat – from demolition, but more often than not from irreversible adaptations.

The Bulgarian real estate market has been seeing constant growth, including concrete blocks of flats seeing record-breaking prices. Why, despite their deficiencies, do Bulgarians trust them enough to make such a major investment?

EK: The answer is not in the building but in the space that the post-war period has created. These buildings exist in a planned environment, organized, well-developed, and well-supported by infrastructure, greenery, and public resources.

While in Bulgarian architecture, as in most post-socialist countries, neo-liberal investment has led to ad-hoc, badly planned, and, as a result, low-quality construction developments – with insufficient parking lots, parks, children’s playgrounds, public transport, kindergartens, schools, etc.

This is the problem with the concrete estates of post-war modernism – they are dull, but they are set in the generous spaces of the post-war welfare state. And now it turns out that many people prefer apartments in aging, prefab neighborhoods just for the quality of architectural space – both outside and inside.

How can these buildings be preserved properly so they continue to serve their purpose without taking away their identity?

AV: There are a number of challenges – and the political aspect is only a fraction. In times of a climate emergency and new priorities, it is expected for architecture to adapt. The expansive concrete buildings with an exorbitant carbon footprint have become inappropriate. However, their demolition is also inappropriate. The future of architecture is in the conservation of the fabric and in adaptive reuse. This is the long-term goal of this exhibition and of the New Architectural Heritage Foundation – not solely to research, analyze and record, but also to propose solutions and to see the wide-scale heritage of the recent past as a resource for redeveloping our towns and cities.