With the rise of the American Tea Party in 2009, the idea of taking part in a political movement associated with a beverage became mainstream on a global scale. However, if tea is too bland for your taste, you are welcome to go back a few years earlier to the height of the Polish Beer-Lovers Party. Conceived as a tongue-in-cheek political protest/cultural statement, it became part of parliamentary order in the early 1990s.

Alcohol plays an integral role in many of Poland’s social, cultural, and even religious practices. However, its consumption pattern has changed over time, usually in line with general cultural shifts. During the reign of socialism, Poland, despite numerous efforts, largely remained a vodka country. The share of spirits in the market never fell below 80 percent and was sometimes as high as 90 percent.

Satirical organizations gain ground

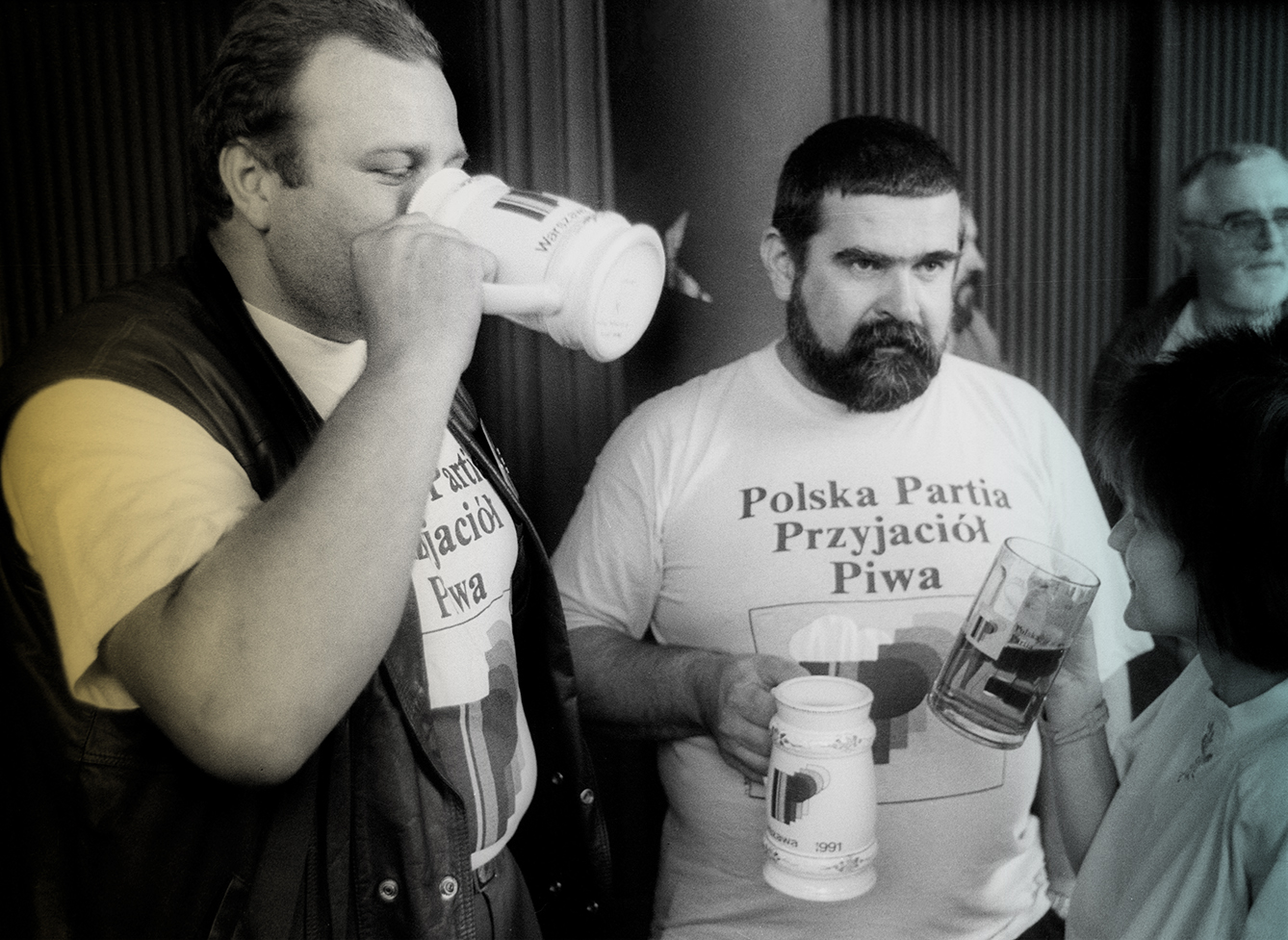

With the advent of political, economic, and cultural change, a shift in this field was also expected. One of the first signs of this shift was a comedy TV show, “Beer Boy Scouts” (Polish: “Skauci piwni”). In one of its famous sketches, group leader Janusz Rewiński, a bearded, bear-like, thirty-something dressed as a boy scout, struggles to enumerate the advantages of milk over beer. The show gave birth to a social movement.

However, it wasn’t the only quasi-dadaist effort at the time. Other satirical political organizations like the Orange Alternative (Polish: Pomarańczowa Alternatywa), a Wrocław-based, anti-communist organization whose members organized political protests dressed as dwarves, also gained prominence. The general idea was that state socialism, with its solemn execution and strict code of conduct, didn’t have the political tools necessary to fight satire. So, for example, when members of the Milicja police force were seen arresting a dwarf, they were automatically ridiculed.

From Beer Boy Scouts to Beer-Lovers Party

Such was also the concept behind the Beer Boy Scouts – a rather unexpected connection between a youth scouting and service organization and enjoying a beverage that is both alcoholic and introduces informal, friendly social relations. Such was also the underlying narrative of modernization – that not vodka-drinking but English-style pub visiting is the proper form of using the benefits of alcohol.

In later interviews, members of the party can’t strictly recall who had the idea of forming it. Some claims point to the men’s magazine of the era, “Pan” (“Gentleman”), whose editor-in-chief Zbigniew Chomicz was a part of the project. The idea was somewhat vague, and the party’s platform, based on the idea of just having a beer, summed up to “let’s talk it through.” But in the heat of the political turmoil in the early 1990s, this kind of platform was more than enough. The Beer Lover’s Party in the parliamentary election of 1991 received over three percent of the votes, which translated to 16 MPs in the 460-seat Polish parliament.

However, following an all-too-familiar pattern, the parliamentary club was soon divided into two fractions moving in different political directions. Some members remained active politicians for some time or even to this day. The face of the party, Janusz Rewiński, chose to stay true to his comedic roots. But then again, in this day and age, the line between the comedian and politician is not as clear cut as it once was.