Today, the Museum is home to a collection of over 160 icons showcasing the work of generations of iconographers from local families, known centuries later all over Bulgaria for their craft. But Bulgaria’s school of iconography is still around.

Today, the old traditions are being carried out by a small group of dedicated iconographers. For decades, the Faculty of Orthodox Theology at St. Cyril and St. Methodius University of Veliko Tarnovo has been the only institution in Bulgaria training future iconographers. Currently, there are about 20 students attending the University’s “Church Arts” program.

Trynava: reviving icon painting

“Unfortunately, in recent years, we’ve been seeing a decrease in students, a consequence of the demographic crisis facing Bulgaria. But regardless, there is interest in this specialty. We offer an academic education that is not affiliated with the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, but our students – an equal number of men and women show interest in this discipline – do have a connection to the Orthodox faith,” says Prof. Miglena Prashkova, a professor of icon painting at the University’s Department of Church Arts who has been working in this field for 30 years.

According to historical evidence, the roots of iconography are in the early Christian era. The earliest images were found in underground galleries, known as catacombs, inhabited by Christians before the establishment of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire in 313 AD. The 8th century was a period of iconoclastic heresy, with Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (685-741) declaring war on icon worship. During his reign, icons were burned, mosaics with Christian themes destroyed, and those venerating icons were executed or subjected to cruel torture. In 787, the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea officially restored icon veneration.

Freedom to form icon museum

The history of Bulgarian icon painting dates back more than a thousand years. In 864, when Boris I of Bulgaria accepted Christianity as the official state religion, iconography became intertwined with the history of the Bulgarian state. “With Bulgaria’s conversion to Christianity began the mass construction of temples and their corresponding decoration with frescoes and icons. The Byzantine influence was very strong, as this was the Mother Church from which we received the faith and the Byzantine styles, which are reflected in the Bulgarian icon painting.

Gradually, nationally distinctive traits were formed in native icon painting,” explains Prof. Rostislava Todorova-Encheva, lecturer at the Department of Visual Arts at The Constantine of Preslav University of Shumen. Developed over the centuries, iconography in Bulgaria received a major boost during the National Revival period, which ended with Bulgaria’s independence from the Ottoman Empire (1762-1878), with new schools producing precious works in the towns of Tryavna, Bansko, Veliki Preslav, and Samokov.

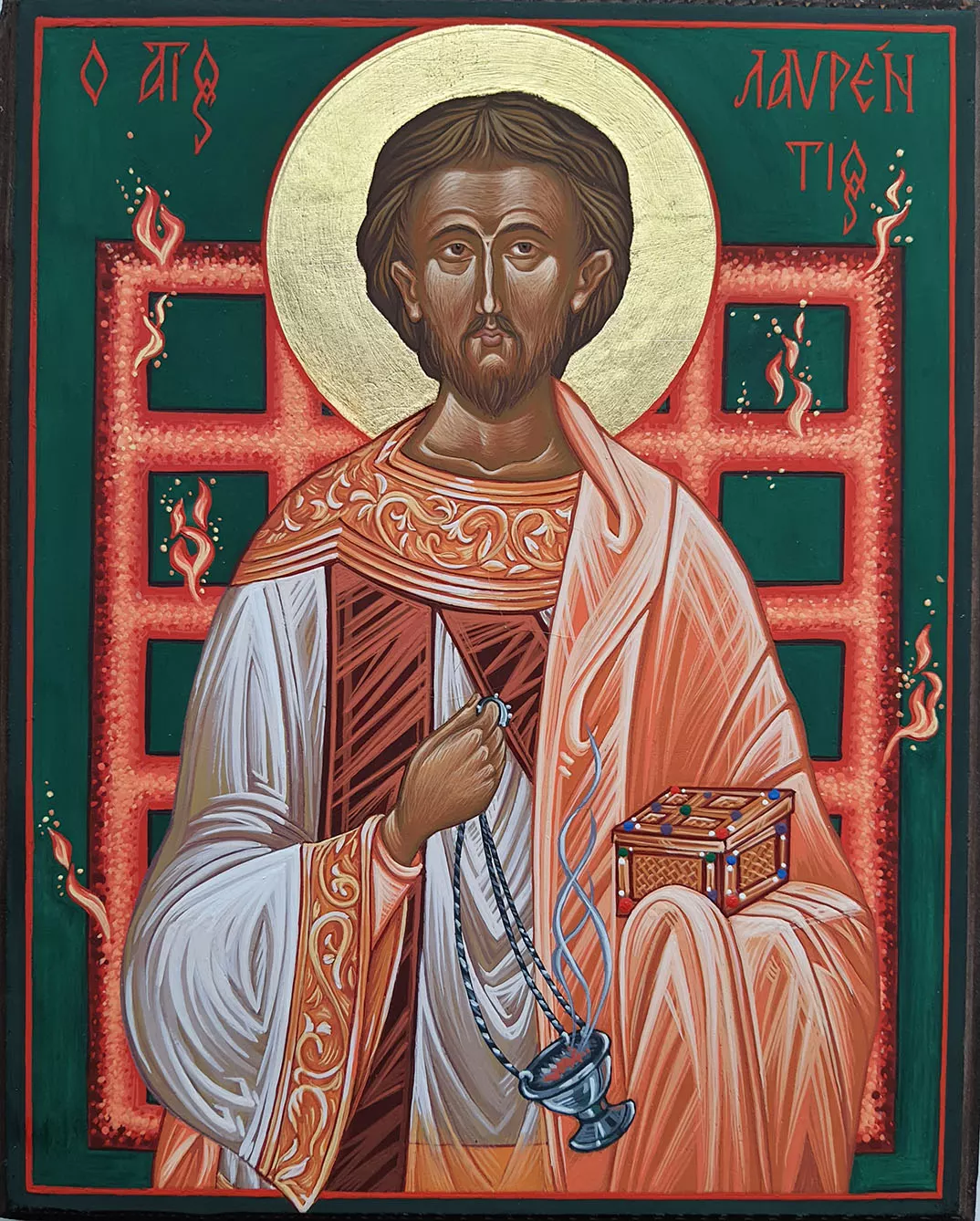

Professor Todorova-Encheva doesn’t keep a record of the exact number of icons she has painted over the years. “To really paint an icon, not just an artwork, you must first have a relationship to iconography. And that is formed by knowledge of the faith. You need to know whom you are painting. You need to be aware of the meaning of each icon which is not the object of worship. The subject from whom you ask help and protection is the sacred personage, the saint,” she says. “When commissioned, people insist that the iconographer be ecclesiastical, with an attitude of faith. Not random artists who paint portraits, just pictures.”

Genotype of the nation

Can someone with an untrained eye spot the differences between various schools of iconography within the various national Orthodox churches? “Everywhere, the stylistics depends on nationally peculiar features, although the requirements of the canon are observed. Something of the genotype of the very nation to which the iconographer belongs inevitably comes through in the features of the faces. But the canon does not limit the iconographer. It gives him certain guidelines. The iconographer is bound to show creativity,” comments prof. Todorova-Encheva.

After completing their education, “Church Arts” graduates continue to work in the rare field, painting icons and murals, alone or as a part of a creative collective, with commissions coming both from churches and individuals. There are also those who go on to become gallery directors, museum curators, and art teachers. A few choose to become priests or work in the structures of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, says Prof. Miglena Prashkova, “We also have graduates who made it abroad. Two girls live and work in Paris as artists. Our students also work in Austria and Spain. It takes time and dedication to become an icon painter. Icons are painted only with a pure heart and pure thoughts. For me, it is a choice you dedicate yourself to.”