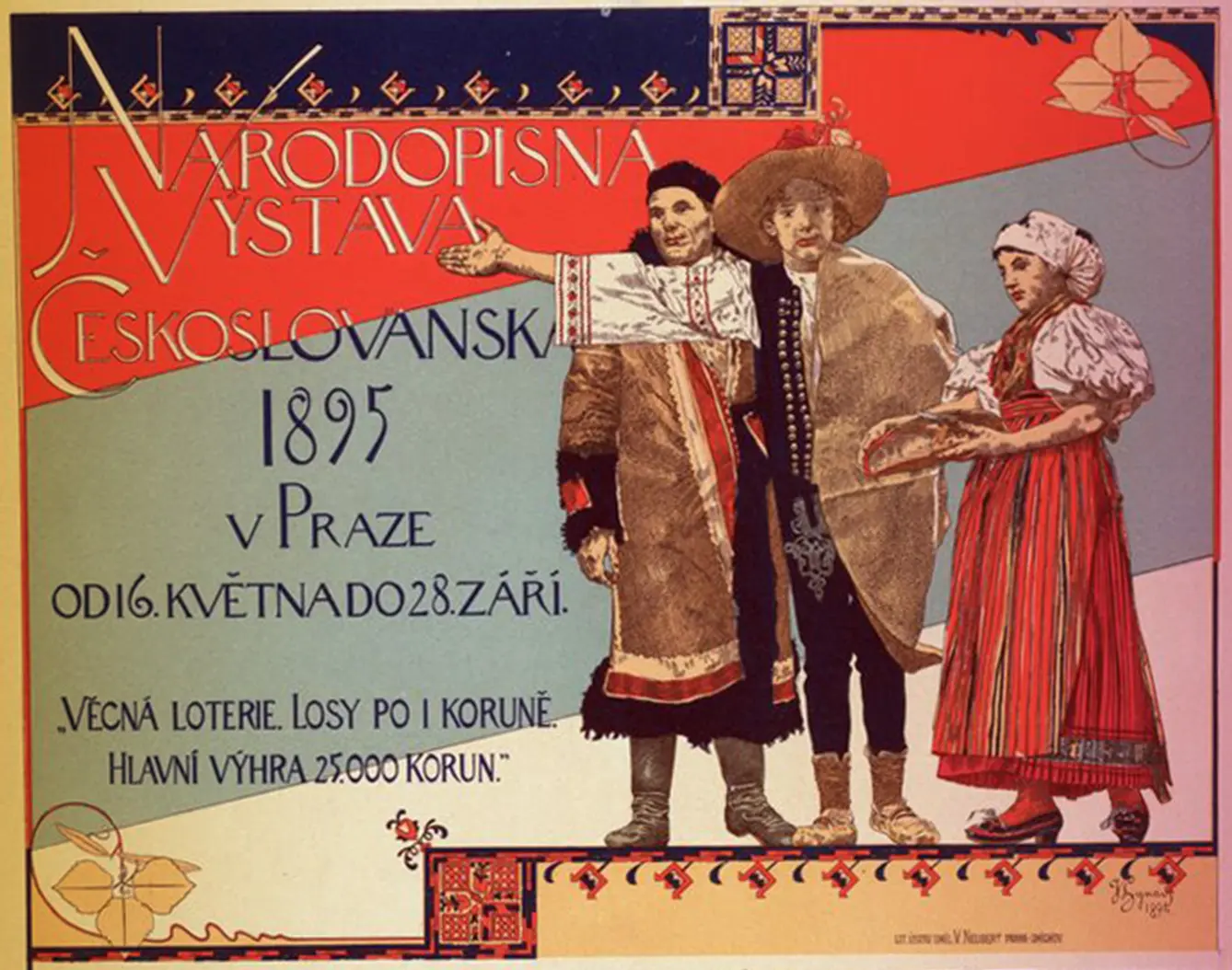

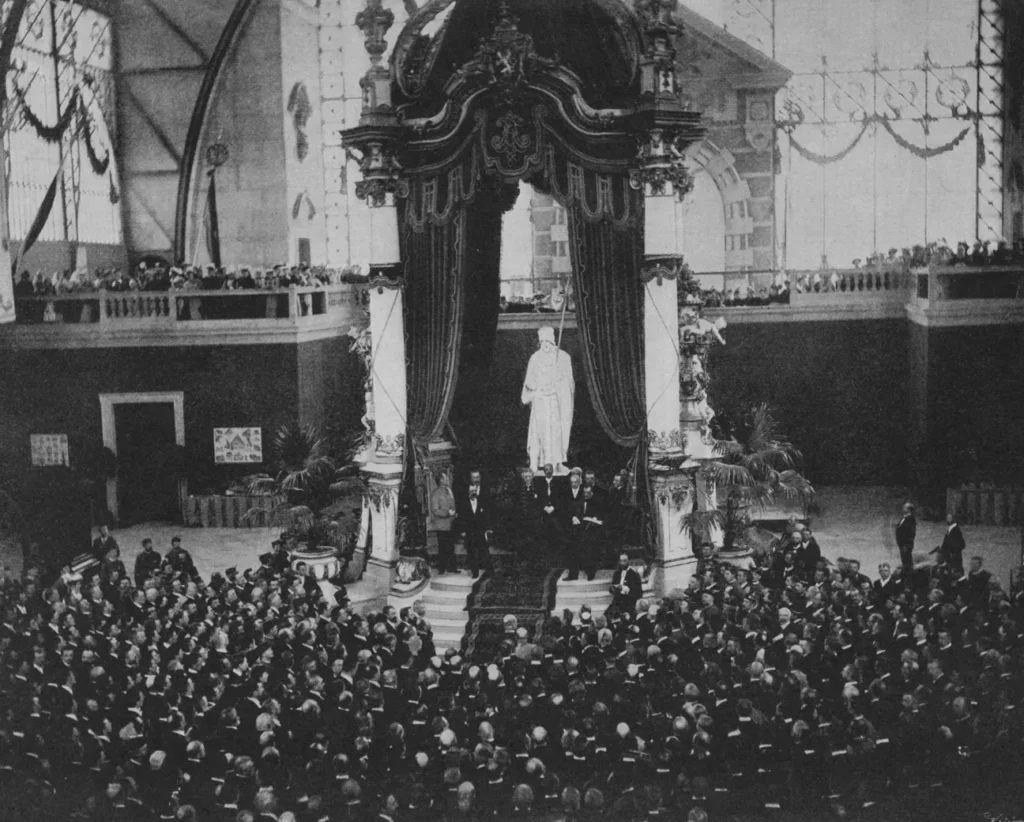

In 1895, a staggering number of over two million people came to see The Folk. Of course, it was not in just one day – the Czechoslavic Ethnographic Exhibition was open for visitors from May to October to spark interest in the rural traditions of the countries – and boy, did it live up to this purpose.

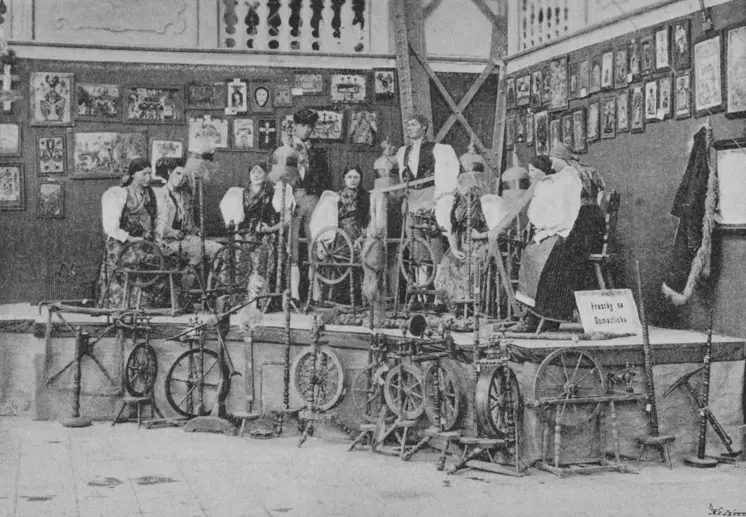

Authentic exhibits of peasant culture from Bohemia, Moravia, and Wallachia, Czech ethnicities, were displayed. There was art, products of everyday life, architecture, and artifacts. Traditional costumes were presented on life-scaled figures, and the village was formed. It contained houses of different building traditions and purposes (such as homes and taverns), filled with authentic people wearing traditional costumes and pretending to do their “traditional” stuff.

Folk exhibition. Literally

Wait, what? People as specimens in the exhibition? In a way, yes, and the setup of the Czechoslavic Ethnographic Exhibition was true to the Zeitgeist. To fully grasp what it was about, look at a broader perspective: what Czechia was back then.

And what it was is a part of a much larger political entity known as the s Austro-Hungarian Empire. Consisting of many territories, now separate nation-states, it was a dual monarchy: called Cisleithania and Transleithania. The former, the northwestern part of the empire, was a bit more “Austrian” than the latter, the more “Hungarian.”

Czechoslavic Ethnographic Exhibition: more Czech than Slavic?

The year was 1867 when Habsburg Empire ceased to be Austrian and became Austro-Hungarian instead, admitting that the Hungarian nation was large enough to be named as a part of the equation. So, why wasn’t Czechia? This was a question Czech intelligentsia set to answer, showcasing Czech folk and its traditions during the Czechoslavic Ethnographic Exhibition of 1895.

Slovaks were also invited to include “their” folk but were hesitant. The reason was mostly the division: Transleithanian country wasn’t at ease with the Cisleitanian organizer of the exhibition. Still, it was the Czechs’ party, and everyone was invited, and millions of people from around the Empire took the occasion.

And, upon their visit, they must have had a good sentiment, as soon all kinds of folk festivals became popular and were so throughout the 20th century. It’s also hard not to notice that Hungarians answered a year later with their Millenial Exhibition of 1986 in Budapest’s Varosliget commemorating the history, deeds, and present condition of the Hungarian nation. It took another few decades to straighten up national divisions and pretensions. Luckily, now, every nation can have its own folk craze.