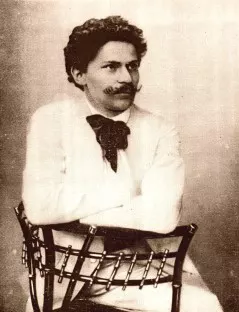

As with every good invention, the story of its creation is not free from controversy or legal disputes (times really don’t change much!). But before we get to that, let us reveal the name of the man behind the life-saving garment. Jan Szczepanik, born in 1872 in Rudniki, in south-central Poland, was a teacher and inventor, nicknamed the “Galician genius.” Many of his inventions were so ahead of their time that they never made it to mass production as the technology to produce them was lacking, and costs would exceed the potential profit.

He wanted to color the world

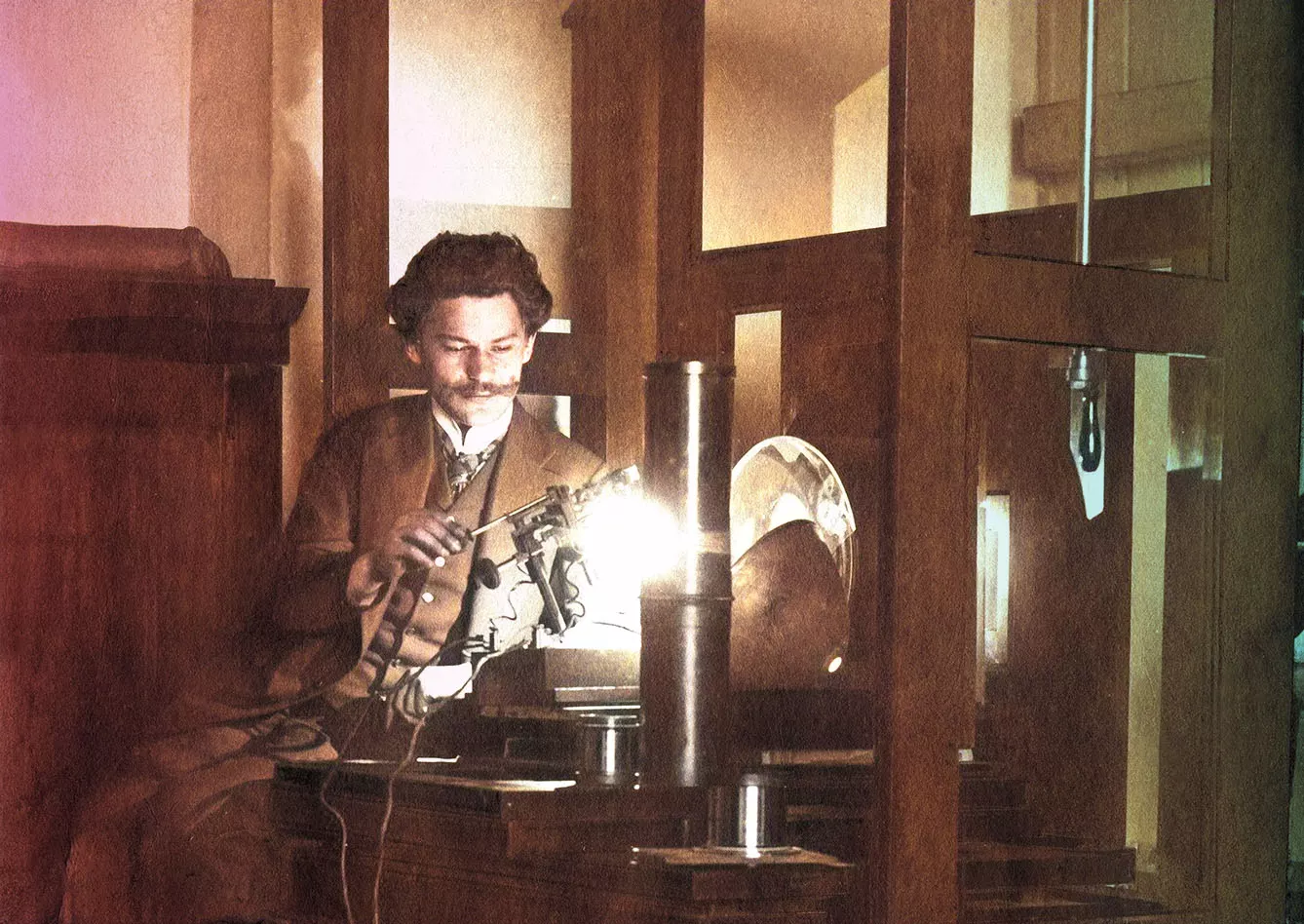

Just to illustrate how much of a visionary Szczepanik was, we need to travel back in time, back to when photography was merely a novelty. The first photographic picture was taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. However, modern photography is said to have evolved thanks to the works of William Fox Talbot, who in 1839 presented his idea of light-sensitive paper. Then in 1899, only 60 years later, Szczepanik, who was 27 years old at the time, presented his invention of a small-framed colorful film.

But that was not his only input in trying to brighten up the grey reality. His invention of the color weaving machine was so groundbreaking that even Mark Twain wanted to purchase the rights to the device. Even though he was unsuccessful, what remains of his interest in the device is a tapestry with Twain’s likeness, designed by Szczepanik and produced using his weaving machine.

His work in the field of photo-textile manufacturing was astonishing to his contemporaries, who suddenly were able to easily recognize whom the textile images were depicting (Piłsudski looked like Piłsudski, Mościski like Mościski, etc.) Let me leave you with one last genius idea of Szczepanik – the telectroscope. The device was meant to send motion pictures and sound and earned Szczepanik recognition as one of the most significant precursors of modern television.

Bulletproof vest: a practical invention for troubled times

Keeping in mind just how prolific the Galician Genius was, let’s learn about the story of his most famous invention, namely the bullet-proof vest. Its development quite literally changed the course of history and is still these days the basic equipment used by law enforcement units.

To be fair, Szczepanik was initially invited to cooperate on the bullet-proof project by a monk, Kazimierz Żegleń. They agreed that Szczepanik would continue working on his idea and pay him a monthly salary. Should the invention be successful, they agreed to split the profits evenly.

However, Szczepanik’s input in the design was so fundamental that, in the end, he arrived at a completely different construction, which caused a later discord between the gentlemen. Because he felt like he had conceived an independent idea, Szczepanik claimed full rights to the vest.

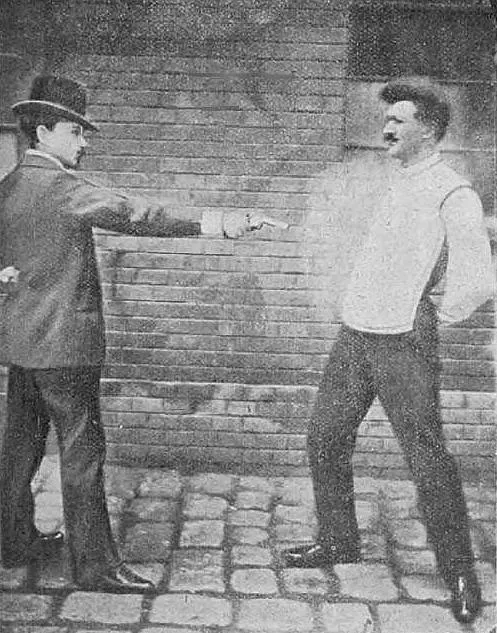

Its construction was simple yet brilliant. A unique weaving technique Szczepanik invented weaved threads of silk reinforced with metal plates that would slow down and entrap a bullet, causing it to lose momentum. And it worked. Word of the new invention spread fast, and customers soon flocked to the Polish mastermind, including royalty – the Spanish crown was among them.

The walls of the royal carriage were covered with the material, saving the life of the 16-year-old King Alfons XIII. The ruler was so grateful that he decorated Szczepanik with the order of Isabela the Catholic – the highest order in Spain. Nicholas II of Russia also wanted to show his appreciation. However, Szczepanik refused the honor of being awarded the Order of Saint Anna for patriotic reasons. Instead, the emperor presented him with a golden watch and a brooch for his wife.

The green-eyed monster strikes again

The overwhelming success of the vest had one (jealous) adversary – Kazimierz Żegleń. He must have felt hard done by his former friend enjoying all the recognition for the life-saving material while he had nothing to show for his input and the original idea. In the end, instead of lengthy disputes in the court of justice, Żegleń sold his patent for 30 thousand rubles. And although he would not partake in the glory surrounding the bullet-proof vest during his lifetime, he certainly achieved one aim – his name is still mentioned as one of the precursors of the invention.

Although widely respected by his contemporaries, Szczepanik was seen in his hometown of Tarnów as a bit of a misfit, with his head constantly away with the science fairies. His daughter Maria remembered him as a loving father who, when not at work in one of his factories in Berlin or Vienna, would completely dedicate his time to his kids. He would take his family to Krościenko nad Dunajcem for luxury holidays (one could wonder how many times he took them for rafting). She said he owned a dozen suits but would always wear the same one.

Szczepanik died of liver cancer at only 54. Nevertheless, his legacy lives on, and Tarnów proudly keeps the memory of one of the greatest Polish inventors alive.