The pine marten, or in Latin, Martes Martes, is a small mammal that kind of looks like a weasel or a ferret and can grow up to half a meter long and weigh up to two kilograms. They can be found in almost all of Europe but are especially prevalent in the Southeast. Martens, known for their fur thick fur and long tails, are endangered and strictly protected these days.

However, this was not the case in the Middle Ages. During the time of Croatian kings in the 10th and 11th centuries, several present-day Croatian islands were owned by Venice and paid taxes to the Venetian administration in marten skin or marten fur. Marten skins were highly prized for their durability, and the luxurious fur was considered first-class, with numerous kings and rulers seeking to wrap themselves in it for warmth and prestige.

Worth their weight in gold

Over the centuries, marten fur and skins spread and became a precious form of payment for things besides taxes in other parts of modern-day Croatia, all the way to the Slavonia region in the Pannonian Plain. This was true in the Slavonian city of Pakrac, located near the forest-covered Psunj Mountain, which is the habitat of the golden pine marten. This animal was a bit of a pest to the locals, thanks to its predatory nature and penchant for hunting smaller domestic animals. Thus, it was especially appreciated in the city when someone caught a marten.

As it so happens, Pakrac was also the site of one of the first mints in Croatia, where “banovac” coins were minted in the 13th century. On the front, the coins featured the image of the Croatian-Hungarian king. On the back – you guessed it. A marten. Banovac coins quickly spread throughout the region, and the marten became a recognizable symbol.

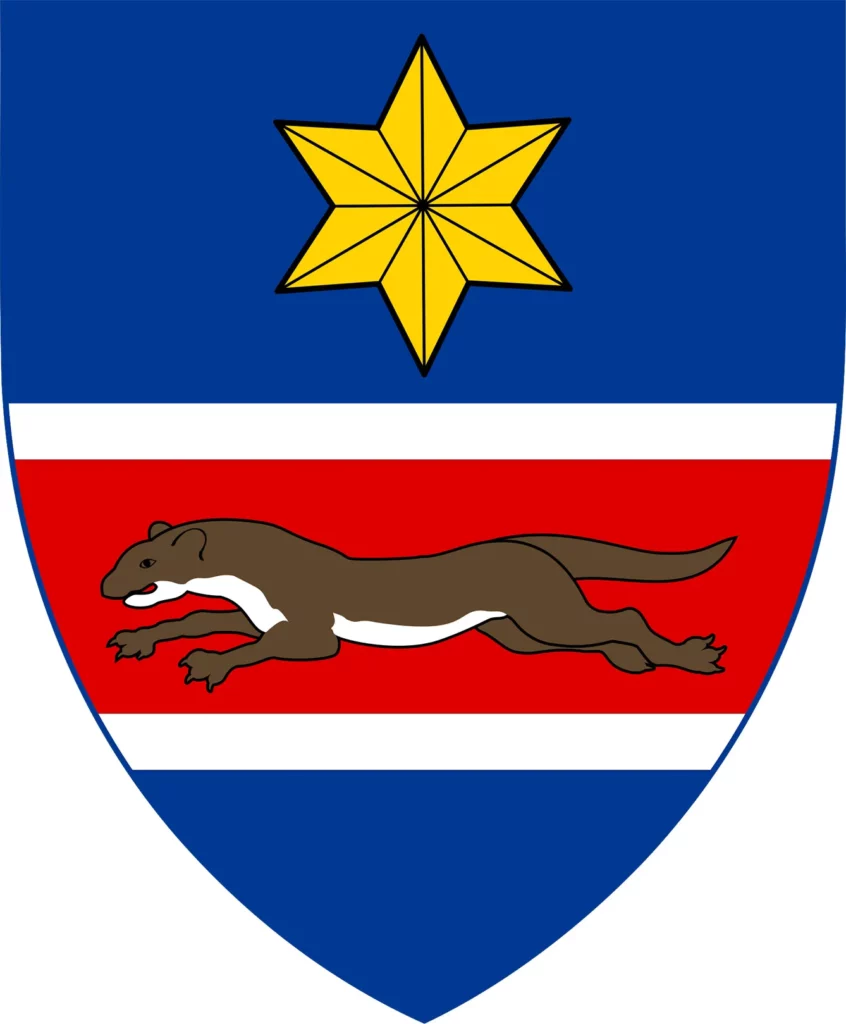

In addition to coins, in the 15th century, the pine marten also appeared on the Slavonian coat of arms. Perhaps by accident or perhaps on purpose. There is a story that the king at the time wanted a lion on the coat of arms as a symbol of the previous royal rulers over Slavonia. However, the designer of the coat of arms did not know how to draw a lion because he had never seen one, so he drew a marten instead.

The national animal – or is it?

As different parts of Croatia developed under different governments, they had different symbolic animals; for example, the Istrian coat of arms features a goat, the symbol of Lika is a bear, and central Croatia favored the stork, turkey, and goose. In order to respect the uniqueness of each region, no one pushed the idea of declaring one until the 20th century.

During the Nazi Independent State of Croatia, a currency called marten (kuna in Croatian) was first introduced, harkening back to the old banovac coins. After the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, independent Croatia reintroduced the marten (kuna) currency but firmly distanced itself from the Nazi past. Thus, until the last day of 2022, when Croatia switched to the euro, the marten (kuna) was the Croatian currency and, basically, the not-totally-official national animal.

Nonetheless, the switch to the euro did not end Croatia’s monetary relationship with the pine marten. It can now be found on Croatian one-euro coins.