Though the world would collectively agree that 2020 was not a great year, it did have one shining spot: the one-hundredth birthday of the word “robot.” “R.U.R,” or “Rossum’s Universal Robots” (Czech: Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti), was a 1921 play by famous Czech writer and journalist Karel Čapek, which catapulted its author to immediate fame. By 1923, it had already been translated into 30 languages.

Robot: the Czech paesant

The play, similar to another cult phenomenon, “Blade Runner,” which would debut 60 years later, depicts the world around the year 2000 when a wealthy industrialist begins to make human copies. These “robots” are physically identical to humans, with the strength and capabilities to work. However, they initially lack feelings and sentiments and thus do not need necessities like salaries as they lack the desire or need to spend money.

In fact, at one point in the play, a ‘robot’s rights’ advocate demands that the robots be paid for their work, an idea the factory owners find entirely preposterous. However, further advancements lead to the robots developing consciousness, ultimately leading them to rise against the humans and end humanity as we know it.

Luckily, it was just a play, and humanity was not destroyed (at least, we hope?). But here’s the real, lasting legacy of this drama: Čapek intentionally chose not to use the word “android” in the play, which was well-known at the time, and instead coined a new term: “robot.” It is a word with no common base in Germanic or Romance languages, but all too familiar for Slavic languages users. Josef Čapek, Karel’s big brother and a writer himself, proposed the word to his little brother.

The rise of the workers

The author’s first idea was to use the word “labori” based on the Latin word for ‘work’ however, Josef proposed “robot,” derived from “robota.” Even today, across the Slavic-speaking world, the word denotes something connected to work. In Czech, particularly, the word’s historical meaning is related to the feudal economy. “Robota” expressly referred to mandatory and unpaid labor the serfs were forced to perform for their masters.

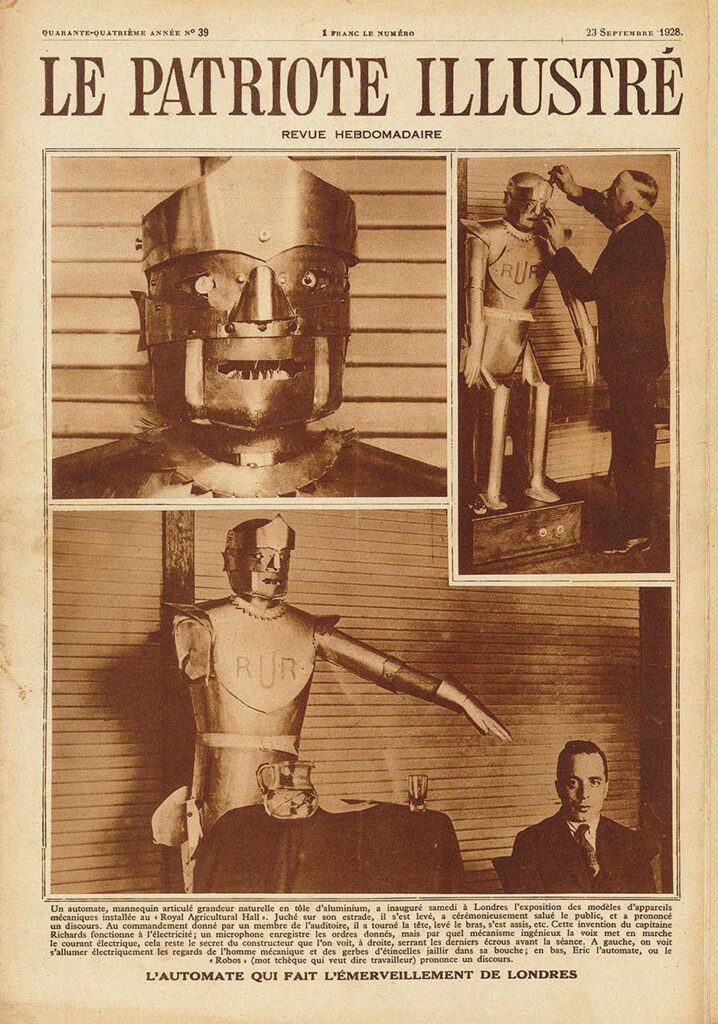

The word ‘robot’ soon took off. Although today, it is more associated with functional, task-performing machines with less-than expressive aesthetics. Why is that? Maybe because of “Eric,” a British tin man built in 1928. Eric greeted guests at the Exhibition of the Society of Model Engineers after the Duke of York, later George VI, canceled his appearance in this role. The chest of Eric the Tin Man, who was able to sit and bow, was fitted with a radio speaker and inscribed with the letters R.U.R.

In the following decade, Eric’s successor was George, an educated gentleman made of steel. And the idea of robot as a machine imitating man soon was widely popular.