When we think about revolution, we imagine pictures of violent outbursts and angry people. But perhaps the most important revolution ever, the Industrial Revolution, was just the opposite – progress and process instead of outbursts. It was a peaceful movement, with just the occasional violence from workers destroying machines out of fear of unemployment.

Sawing machine: driver of the revolution

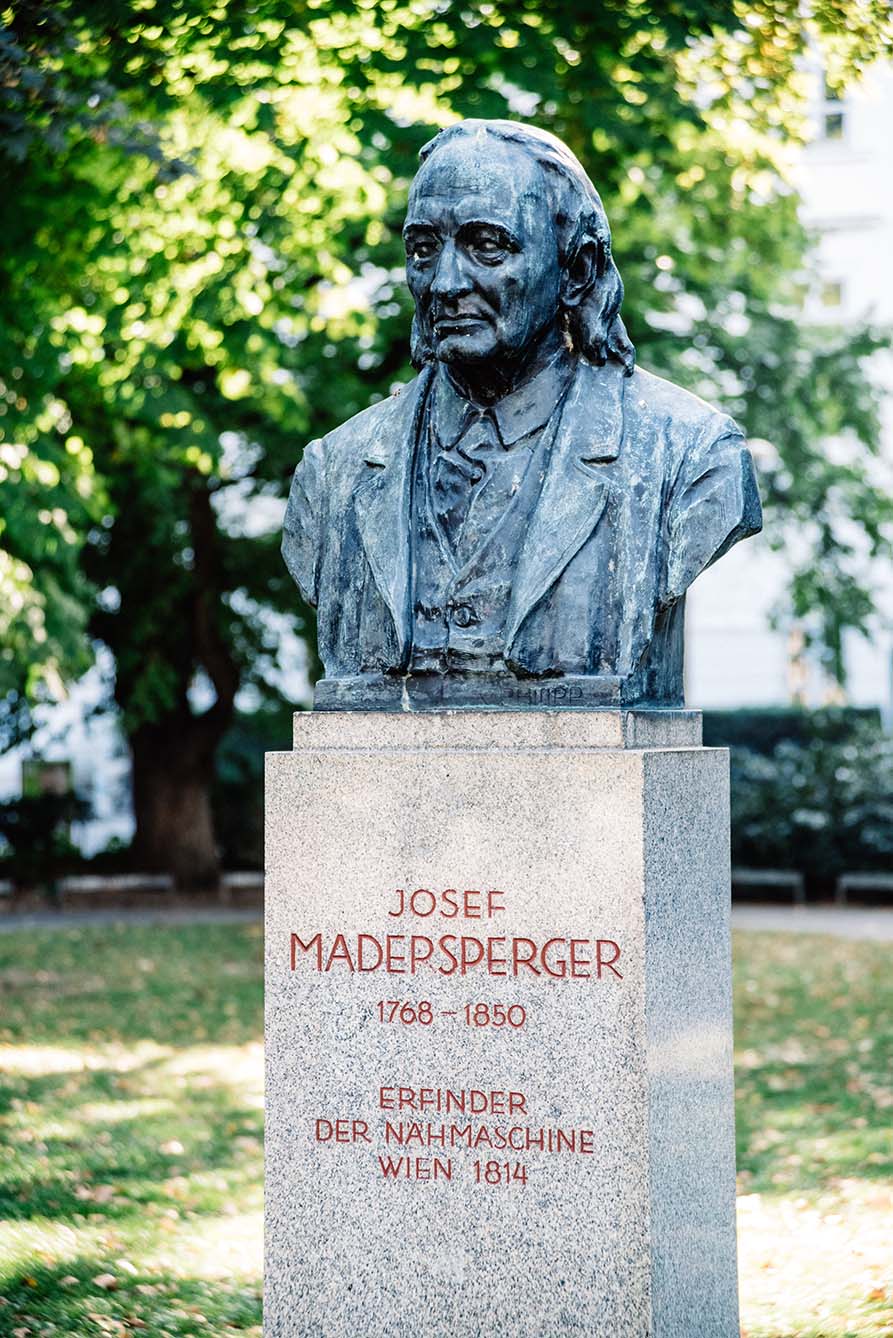

The Industrial Revolution had its machines, though not machines of war. Rather, it was a time when machines for production were created at a breathtaking pace. Among the most important was the sewing machine, as noted by today’s historians and Karl Marx alike. Like many inventions, it has multiple points of origin. One of them was in Vienna, where tailor Josef Madersperger invented a sewing hand.

It’s hard to describe the change in the clothing industry that happened in the 19th century. Before, aristocrats would pay gold’s weight for silk to make their suits and dresses, and poorer class members wore cheap woolen clothes until they turned to rags. But the famous introduction of cotton and even more famous weaving machines, like the Flying Shuttle and Spinning Jenny, led to the supply of cheap fabric. Even so, turning the fabric into clothing required such an immense amount of work and money, people would still mend existing clothes whenever possible.

Sawing hand of Josef Madersperger

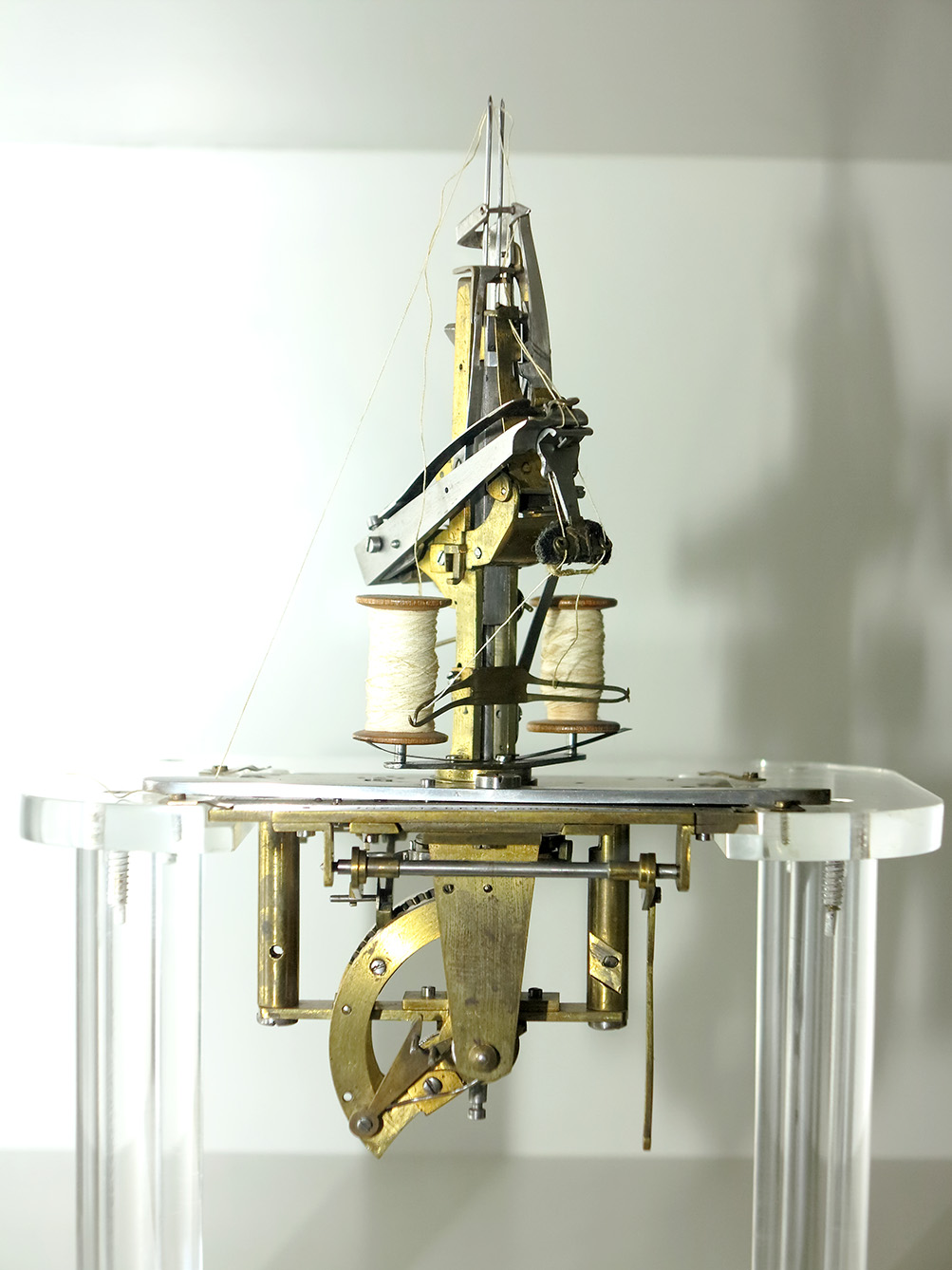

Among those who took to repair this equilibrium was Austrian Josef Madersperger. After their house in Tirol burned down, he and his father relocated to Vienna, where, a tailor by day, he spent his money and free time developing a machine to simplify sewing. After toiling away on his invention for seven years, by 1814, he was ready to present the Sewing Hand, an ingenious design unlike any other. But there is a reason that his machine looks today rather unfamiliar.

He was granted a patent from the Austrian government though he didn’t commercialize it. So by the 1820s, his patent had expired, and he was broke. Yet he built one more sewing machine in the year of inventions, 1839 (*also the year of the first successful attempt at photography). The machine imitated the chain stitching technique.

However, Madersperger was still broke and had no money to set up a factory, so he donated the prototype to Vienna’s Technical University. He was recognized for his work and awarded a medal from the Lower Austrian Craft Society. After his death in the 1850s, he was buried in a common grave, not being able to afford one for himself. However, the tailor’s guild marked his grave with a cast-iron crucifix and continues to maintain it even today. Further recognition came later when streets were named after him in the cities of Vienna, Linz, and Innsbruck.

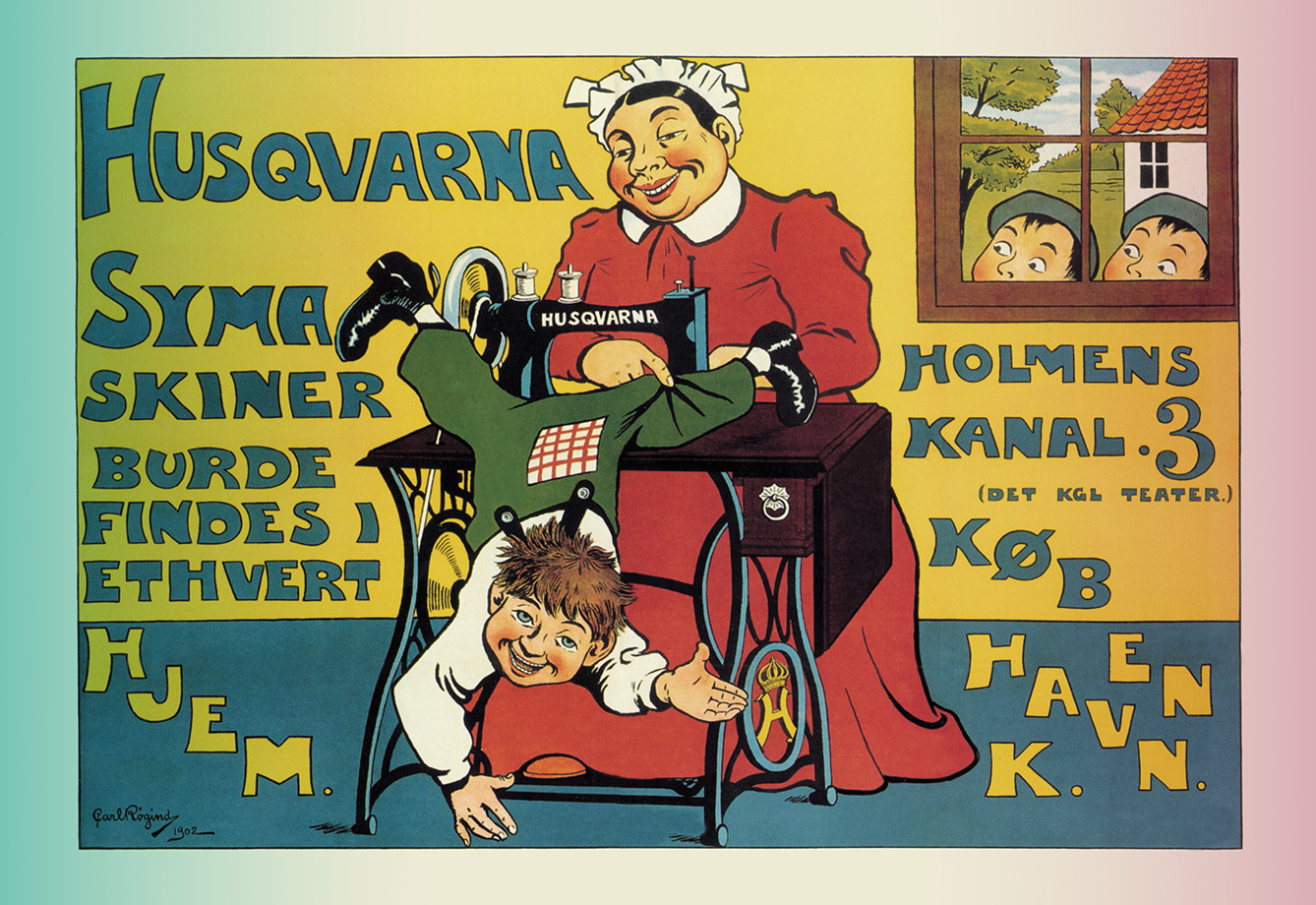

But the true legacy of his invention was evident by the late 19th century when virtually every household had some form of the sewing machine, and sewing patterns allowed home sewists to dress their families without piles of gold.