In the recent AppleTV+ production “Tetris,” which was disappointingly not a videogame screen adaptation but a backstory of its development, we can see the colorful backdrop of socialist computing in the 1980s. Not necessarily accurate in presenting details, it shows one thing accurately: the technology was crude and rare to come upon – but not nonexistent.

It was one thing to use huge mainframe computers in industry or scientific endeavors – remember that the Soviet Union successfully competed against the US in the space race. But personal computers, used in education and, let’s face it, entertainment from the very beginning, were something entirely different. This was especially true at the dawn of the personal computing era in the 1980s in Central Europe, where the households were not wealthy after the crisis times of the late 1970s.

Finding work-life balance

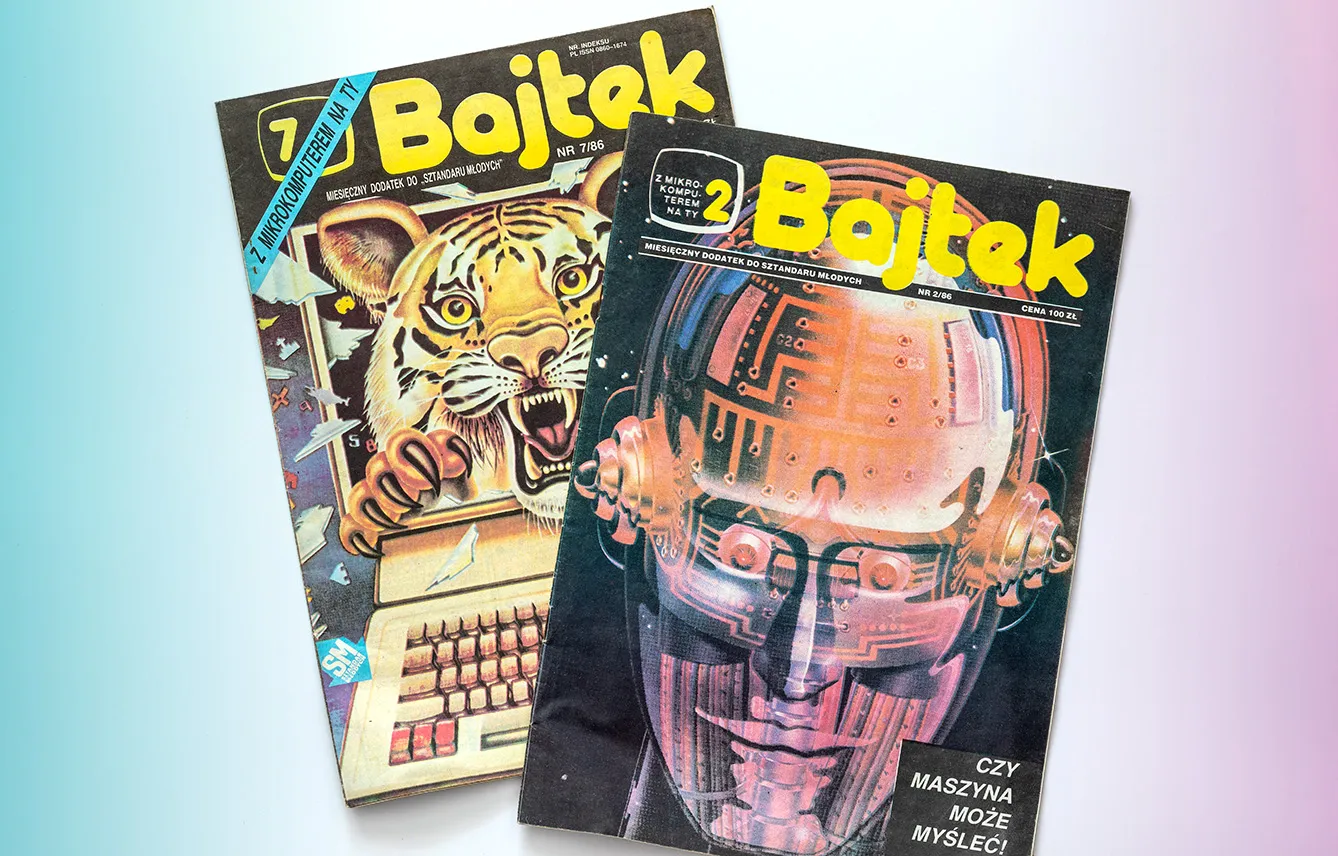

Still, there were attempts at leveling the educational chances between societies, and the state-controlled press was there to help. Polish magazine “Bajtek” was one of them, promoting electronic-life balance since 1985. “Bajtek” was fun in all aspects, and from the very beginning – as the title announced. “Bajt” is the Polish phonetic form of the word “byte” (as in “terabyte” – but decades earlier), but it also rhymes with a boy’s name Kajtek, a playful diminutive, sometimes used to refer to a funny young urchin. This was the first step to making the title approachable and defining the target audience: youngsters.

In September of that year, the very first issue of the magazine claimed that they were there to “fight computer illiteracy.” But was there any? I mean, for illiteracy to exist, there must be letters, and in this case – computers.

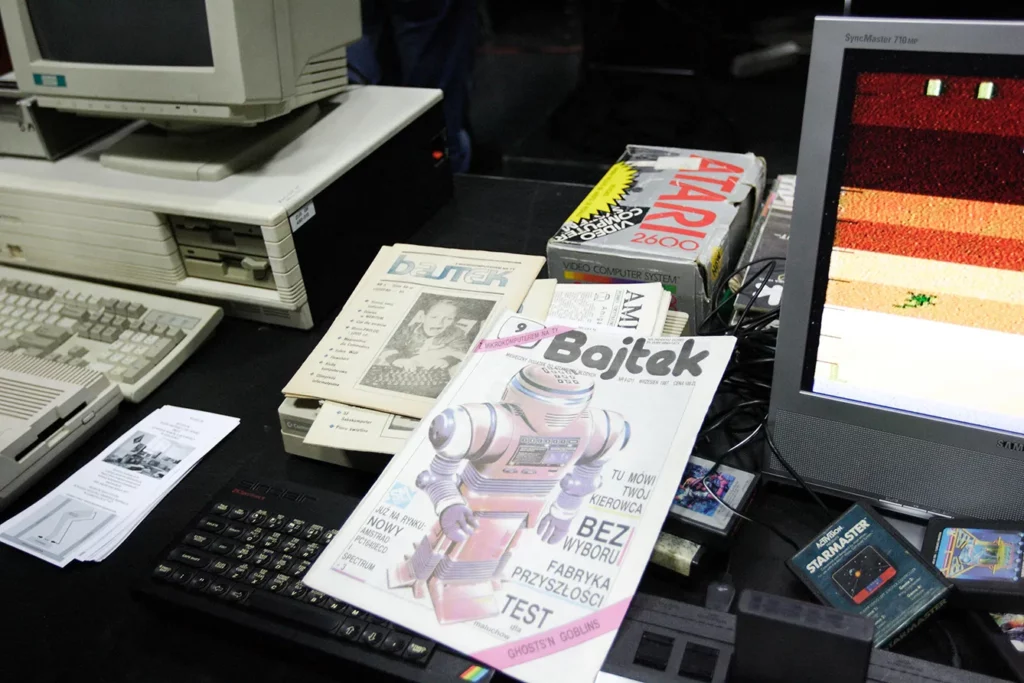

Though several attempts were made at introducing somewhat original Eastern computer designs, in the 1980s, the Western ones succeeded in entering the market. In late socialist and early capitalist Poland, in tiny niches of youngsters with privileged access to computers, there were already forming “electronic” subcultures: the ZX Spectrum guys, the Atari guys, the somewhat neglected Amstrad fans, and later Commodore and Amiga guys, and finally – the IBM.

Where print meets the screen

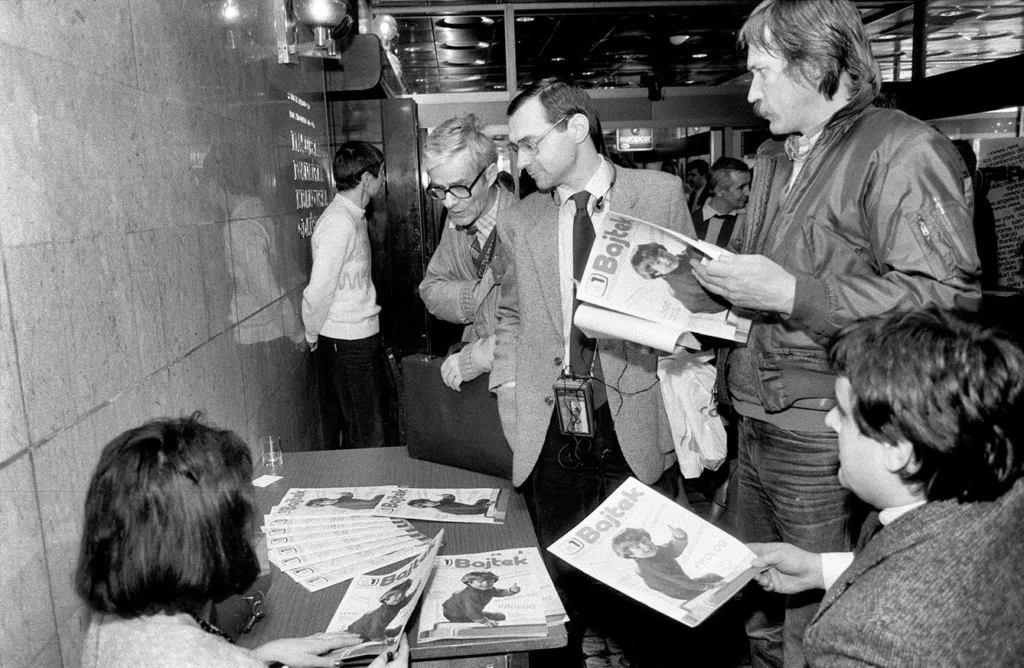

The origins of “Bajtek” is a labyrinth of paths in the centrally planned publishing industry. It was invented and led by Władysław Majewski, who was in charge of the computer column in the century-old “Technological Review,” and the youth communist newspaper “Sztandar Młodych” (“The Standard of Youth”) shared some paper, which was at the time rationed and politically controlled.

The role of editor-in-chief of “The Standard” back then fell to Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who soon became the minister of youth affairs (and you may know him as a two-term president of Poland in the 1990s). He quickly decided that “Bajtek” should be inserted in “The Standard,” and as such, it was published until the fall of communism. Later it became a monthly and then bi-monthly, both published by a newly-formed publishing house that introduced more titles.

The most striking feature of the 1980s “Bajtek” is how informative it was. It covered news from the (electronic) world, inventions, and interviews with engineers and educators. The videogame section presented new games, but was also a social media – with “King and Queen of Games” announced (on an unclear basis) from among submitted bios and photos of children. There was a section for letters and Q&A, as well as classified ads.

Encouraging the youth of tomorrow

Bajtek” encouraged youth to create computer clubs and even awarded “The Golden Disc” (imaged as a 5 1/4″ diskette) for the best of those presented to the editorial board. It compared prices of computers and parts, providing the hungry with the so-needed addresses to get their hardware and parts.

But then, the most valuable part of the magazine is what’s now the most dull-looking. In the time of Basic programming language, you could simply… print a program in a magazine. When someone asked for advice, the solution was not “find a patch on the web” but rather “type this and run.” And, not to hide my nostalgia, I remember spending two days manually typing a video game, only to learn that the enemy I was supposed to shoot was not trying to dodge – perhaps I misspelled one word or overlooked one comma.

In 1990, already under capitalist rules, “Bajtek” publishing house launched its first proper, pure-gaming youth magazine without the didactic narrative of “Bajtek.” The latter survived until 1995 when the market changed. The last issue was published on the wave of nostalgia in 2016 – again, for a niche audience, but this time fueled by memories of times long gone and not the curiosity for innovation. But the nostalgia is real – as “Bajtek” built the first generation of skilled PC users in Poland.