3Seas Europe sits down with Ivaylo Ditchev, Professor of Cultural Anthropology at the Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski,” to discuss what is in store for a country that has some hard choices to make.

3Seas Europe’s Galina Ganeva (GG): In 1989, Bulgaria began its transformation from a communist state in Eastern Europe to something else. Now, in 2022, where are we? Can we call ourselves, even conditionally, a Western country?

Professor Ivaylo Ditchev (ID): The transition process is complete, but the result is not a Western state but something closer to the developing world, where there is also capitalism. Business is no longer run by the ideological state but by informal circles of influence that control the judiciary, the media, and even the absorption of EU funds. The 2020 protests were an attempt to change this, but the political forces of reform have split; perhaps one of them was a Trojan horse prepared in advance. Or maybe we just don’t yet have a coalition culture with clear principles. In any case, there is a distrust of everything, and the informal circles mentioned above are continuously fomenting it. The widespread distrust breeds alienation of citizens from the political process, and in fact, this is precisely the aim of those who govern behind the scenes.

GG: What distinguishes Bulgaria from the leaders of the transition, for example, Poland?

ID: There was practically no dissident movement in Bulgaria before 1989. Only a few were opposed to the regime, and the regime easily marginalized them. In Poland and also in the Czech Republic and Hungary, the building of democracy was undertaken by powerful, organized groups of people who had established trust among themselves during the period of underground struggle.

Bulgaria is not a Western state but something closer to the developing world, where there is also capitalism. Business is no longer run by the ideological state but by informal circles

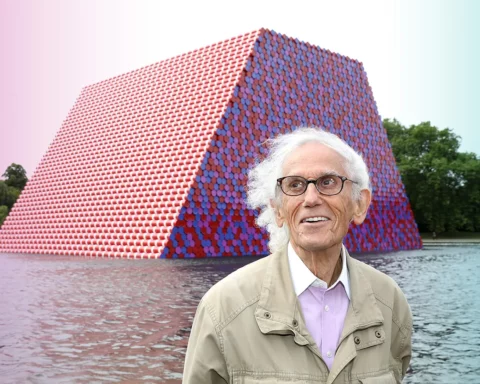

Ivaylo Ditchev, Professor of Cultural Anthropology at the Sofia University

In countries like Bulgaria and Romania, the transition was carried out by Communist Party activists, and the agents of change were the former secret services. Even the intellectuals who actively participated in the first stage were largely linked to the previous ideology and did not sound very convincing. Hence – divisions, betrayals, and scandals.

The main reason was that communism here had raised the level of the common man – unlike in industrial countries like the Czech Republic or East Germany, for which it was a serious step backward. An additional point in our country is gratitude to Russia, the founder of the new Bulgarian state – they instill it in the heads of schoolchildren, hiding other historical episodes. The difference – not only with Poland but with the whole democratic world – we see to this day, in sympathy for the Russian Nazis: up to a third of Bulgarian citizens tend to justify Putin’s aggression.

GG: To that point, why do Bulgarians idealize the past? Could this also explain the strong positions of “patriotic” formations?

ID: The main sadness for the past is related to the defects of democracy – it is very difficult to take decisions, everything is discussed, there are quarrels in parliament, and court decisions are challenged. Totalitarianism appeals because there the political will saves all that – someone says it, and it happens. This is the reason for the ill-concealed admiration for Putin amid the constant dissension in our democratic camp.

Of course, the problem is the distorted view we have of the past – no one cares what collusion there was inside the Politburo, just as we don’t learn today what forces are fighting around Putin.

The past is a weapon of certain political entrepreneurs, but also normal Facebook users who don’t stop posting about how much bread or cheese cost “back then.” Without mentioning what the wages were and how many of the obvious modern consumer goods were simply not on the stands. One such nostalgic person said that in communist times he could easily pay his mobile phone bill (not only were there no mobile phones then, but not everyone had access to even the ordinary fixed network).

Nationalism is a different phenomenon; it concerns the deep complexes of the Bulgarian who goes out on the global stage and feels completely unfamiliar, if not suspicious, with his communist and Balkan past. And bidding in pride begins. Last I heard, they were raising money to build somewhere in the mountains, the world’s tallest flagpole. There you have it.

GG: How would you define the younger generations of Bulgarians who were born already in the EU? Is there anything that distinguishes these young Bulgarians from their peers in the Netherlands, for example?

ID: Well, they feel provincial. From the countryside, one naturally wants to escape and go to the big city. That is, to the west. There is a patriarchy in the countryside, for example, many of these young people are forced to live with their parents until their 30th year because the salary they can get here is usually not enough for rent. In order to leave your parents and become an independent adult you sometimes have to go all the way to Canada.

GG: Moving forward, what path do you see for Bulgarian society, given the war in Ukraine, the misinformation about the EU and NATO, and the looming economic crisis?

ID: The battle is for Bulgaria to find its place in the global world, to de-provincialize. The main striking force of the aforementioned 2020 protests was the Bulgarian youth. Parties like We Continue the Change have emerged, holding a clear pro-Western course and giving hope that it is possible to finally overcome our political autism. Generations in politics are changing; let’s hope we don’t have to wait for the old ones to go naturally (the average age of pro-Russian socialist party members is over 65!).

As for the war, it certainly plays a positive role in this process. Bulgaria needs to fix itself. We have already broken the gas dependence on Russia; the EU is setting the conditions for the reform of the judiciary, and the European Public Prosecutor’s Office is starting to operate. The trouble is that everything is happening very slowly, and social networks are amplifying our impatience.