Austria undoubtedly possesses a showcase of amazing classical composers who were anything but boring. Some of the first that come to mind are probably Mozart and Strauss. But it’s high time that we look at a figure less known nowadays but one that deserves unfading recognition – a Hungarian addition to the iconic and expressive composers.

From genius child to young virtuoso

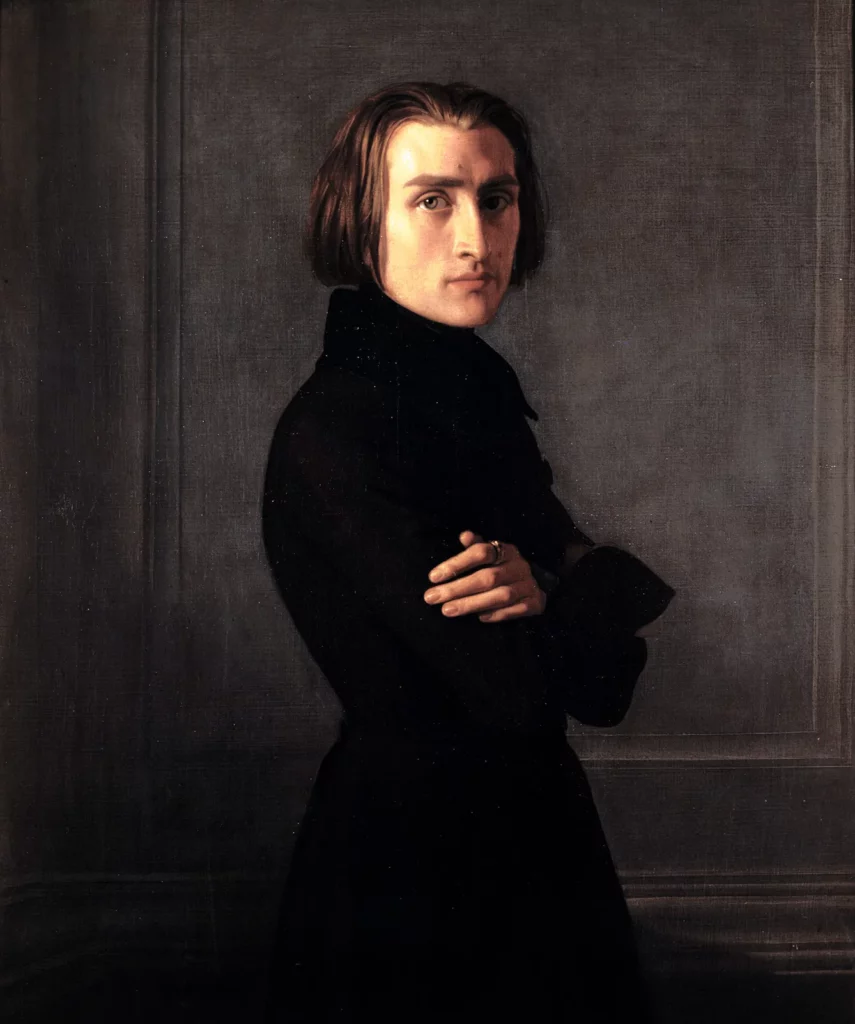

Franz Liszt was born in the Austro-Hungarian city of Raiding in 1811 (today’s Austria). Despite some sources claiming Liszt did not speak Hungarian, he was a Hungarian citizen. Not to mention that his later compositions reflect Hungarian folk music, with the cultural heritage of his father’s homeland ever-present in his works.

Like many awe-inspiring pianists, Liszt showed talent from an early age, reportedly able to read and write notes at seven. There are many accounts of the successful performance Liszt gave at the age of nine at the court of Nicholas II, the Hungarian Prince Esterházy. Although the Prince’s name did not go down very well in history, fortunately for Liszt, his performance was noticed by the critics, which set him on the path to a great career. A career he had to work for very hard.

When rejected at the Paris Conservatory (due to his nationality), his father doubled down on his efforts to train his prodigy son. Interestingly, Liszt’s later skills, which he eagerly showed off, such as his ability to perfectly keep tempo, might not have been, were it not for this private tuition as opposed to traditional schooling methods.

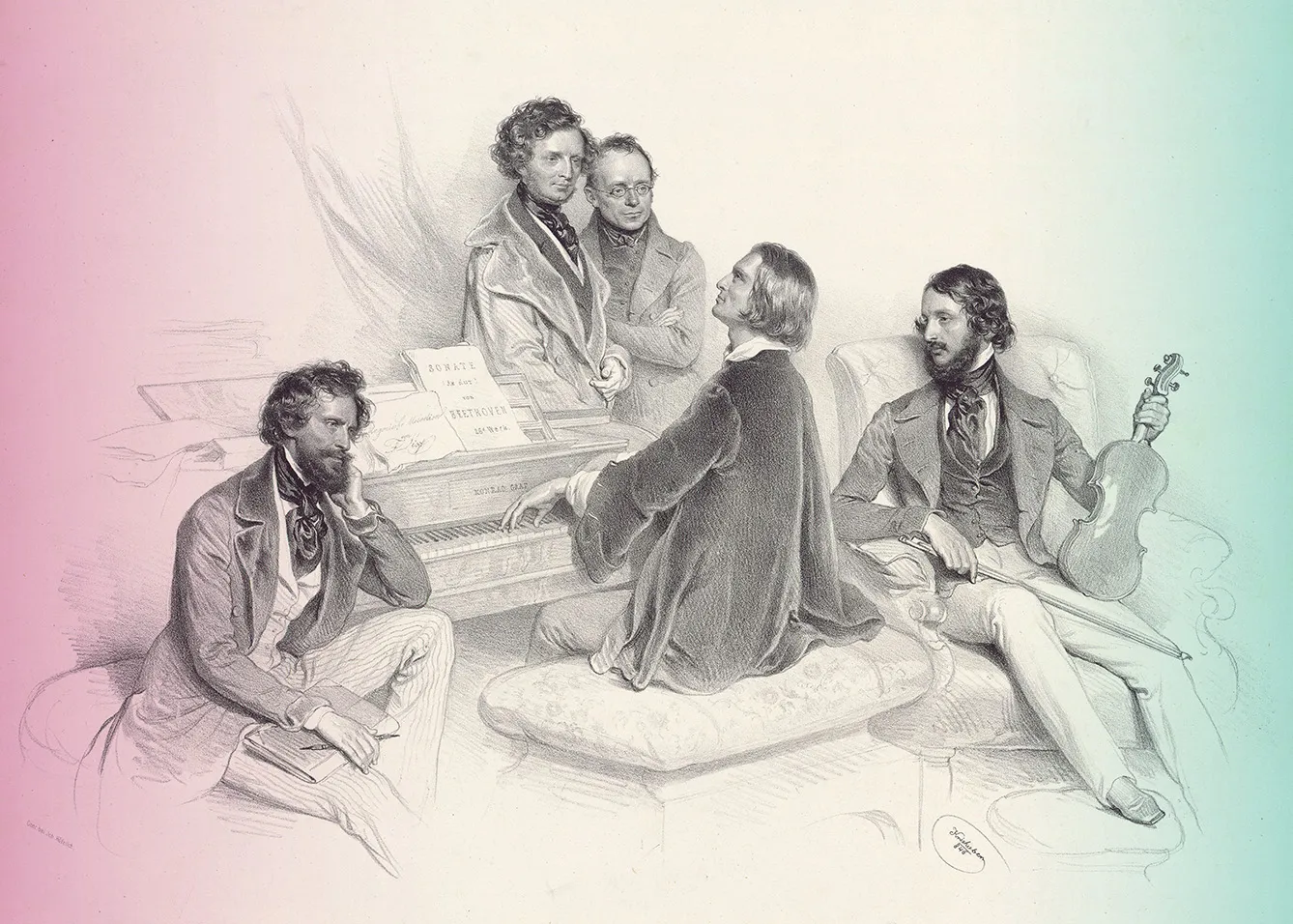

Regardless, Liszt learned from the best (Carl Czerny, Antonio Salieri) and made friends with the best (Beethoven, Schubert, Debussy, Feliks Mendelssohn, Fryderyk Chopin). Whenever proven his genius had boundaries, he worked twice as hard to overcome them.

In a letter written in May of 1832 to his friend, he said: “For the past fortnight, my mind and fingers have been working away like two lost spirits. Homer, the Bible, Plato, Locke, Byron, Hugo, Lamartine, Chateaubriand, Beethoven, Bach, Hummel, Mozart, and Weber are all around me. I study them, meditate on them, devour them with fury.” – Franz Liszt to Pierre Wolff, May 2, 1832, Paris, in Franz Liszt: Selected Letters, translated and edited by Adrian Williams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 7.

In a later part of the letter, he remarked he practiced four to five hours a day and expressed his hope that should he not go mad, he would return to his friend a true artist. His efforts did pay off, and it was eventually difficult to find a match for his skills among the greatest of his contemporaries.

Lisztomania

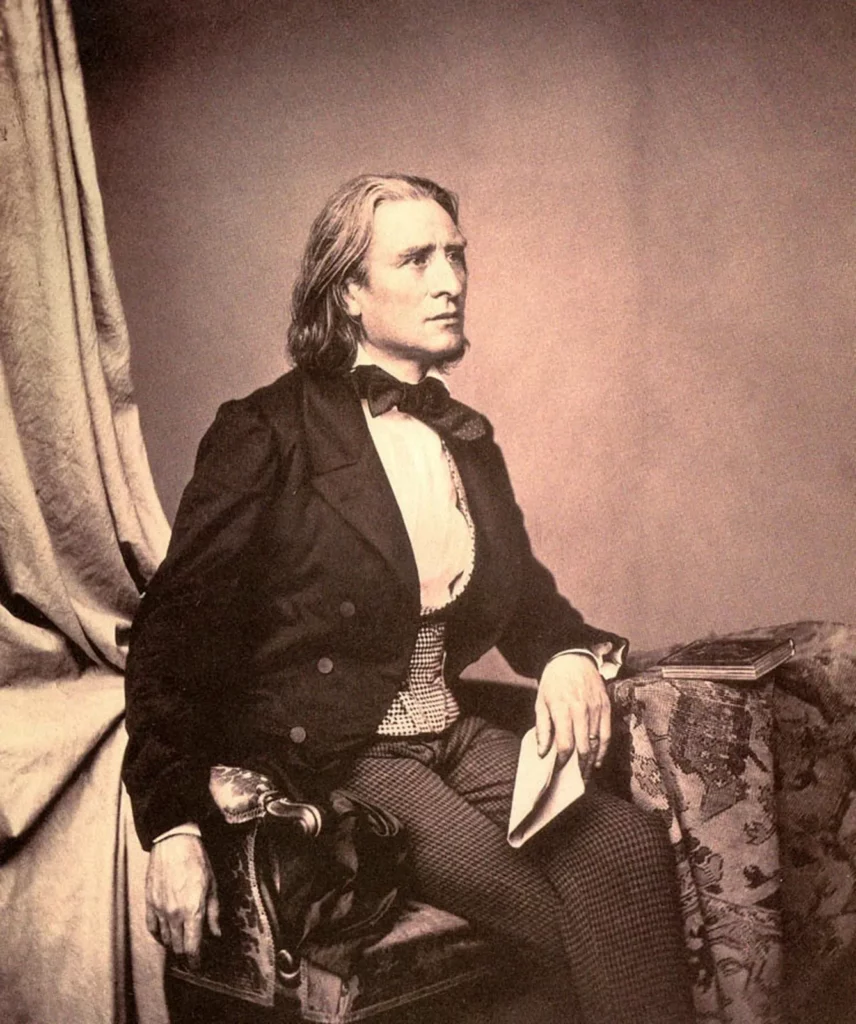

Nature provided Liszt with much more than a brilliant mind and extraordinarily slim fingers, capable of striking notes ten tones apart without much effort. Liszt was also an extremely handsome man, popular with the ladies (*he was particularly fond of [unhappily] married women, who, oh irony, were only the women he formed long-standing relationships with).

If looks and talent weren’t enough, Liszt was one of the first to “break free.” Conscious of his superior skills, he prepared his concerts to show them off most spectacularly. He even forged a new term for the need of his shows – are you familiar with the word ‘recital’ as a music performance as well as its structure? Thank Liszt!

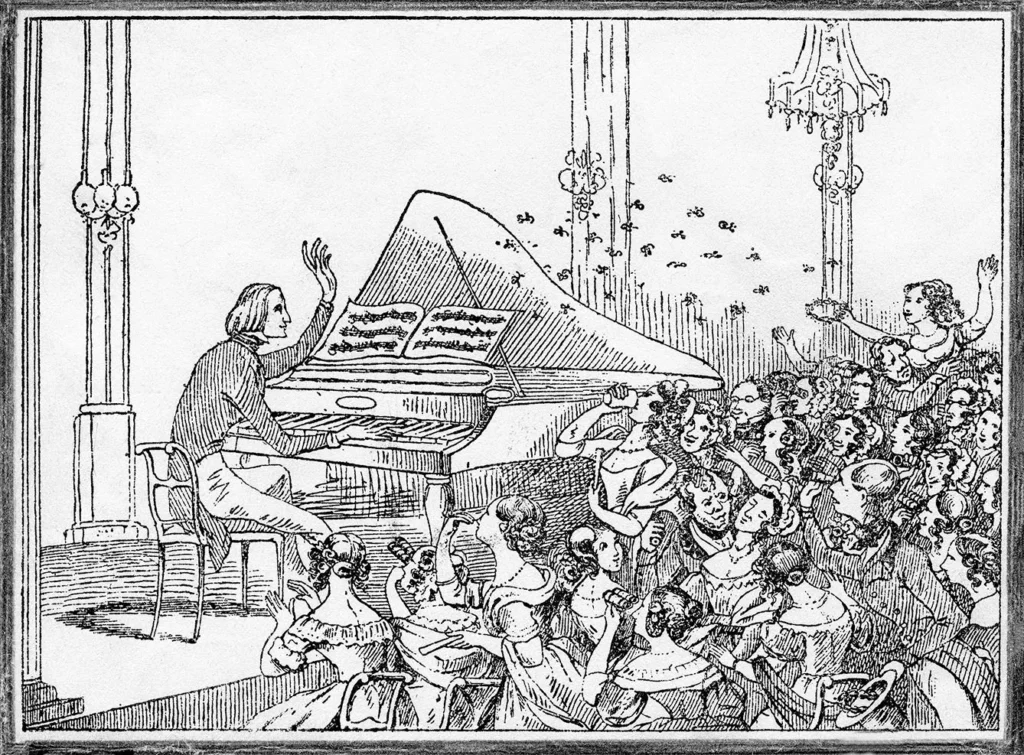

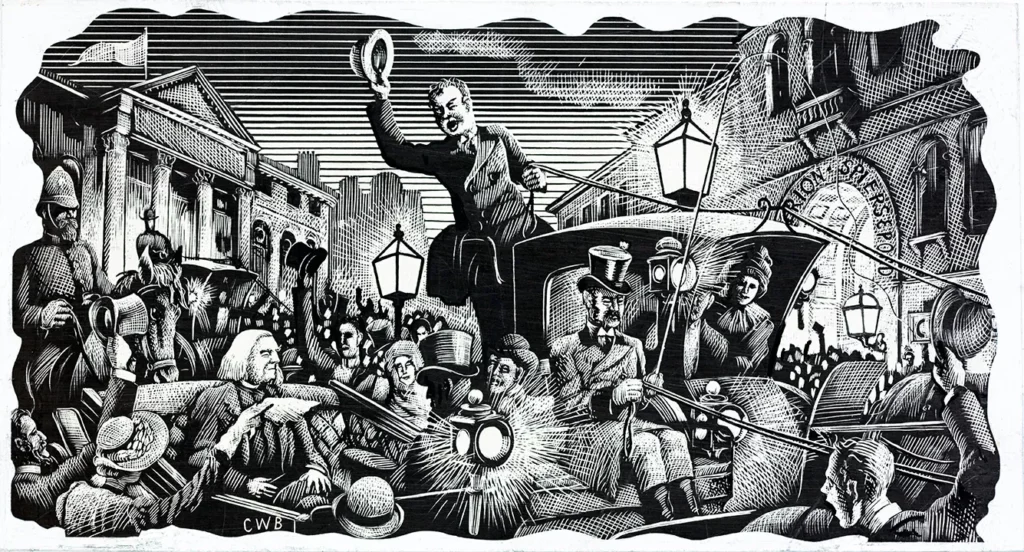

Needless to say, other generations of pianists and snooty members of the audience found it “distasteful” and tried to take away from Liszt’s genius. It seems to have been mostly a case of jealousy, as the public went crazy for the young and extremely talented musician. Liszt was basically the equivalent of an 1800s-style pop icon, and he toured the world more than any other pianist before him. Critics wrote in papers about how they broke into tears after returning from his concerts. Women would faint and gasp at his performances and would not stop at just that.

They would go further, like hunting for pieces of his garment (we will never know if Liszt was fond of handkerchiefs and gloves purely for the dramatic effect dropping them caused among the ladies). Liszt was also most likely the first iconic artist who sparkled full-bodied merchandise – women would wear brooches with his likeness and make bracelets out of broken piano strings (Liszt’s energetic style of performing pushed the strings to their limits and won him the title of ‘string breaker’).

Do you think that is crazy? Ladies would go as far as collect his used coffee grounds and cigarette butts! The above events inspired a German Romantic poet, Heinrich Heine, to come up with the term Lisztomania.

Unlikely inspiration and… plagiarism?

It is actually rather surprising that the inspiration to become as good at the piano as Liszt became resulted from his acquaintance and inspiration found in… a virtuoso violin player, Paganini. When Liszt saw him on stage, he decided: “That’s it! I am going to compose pieces that can help me prove what I am capable of!” And prove it he did.

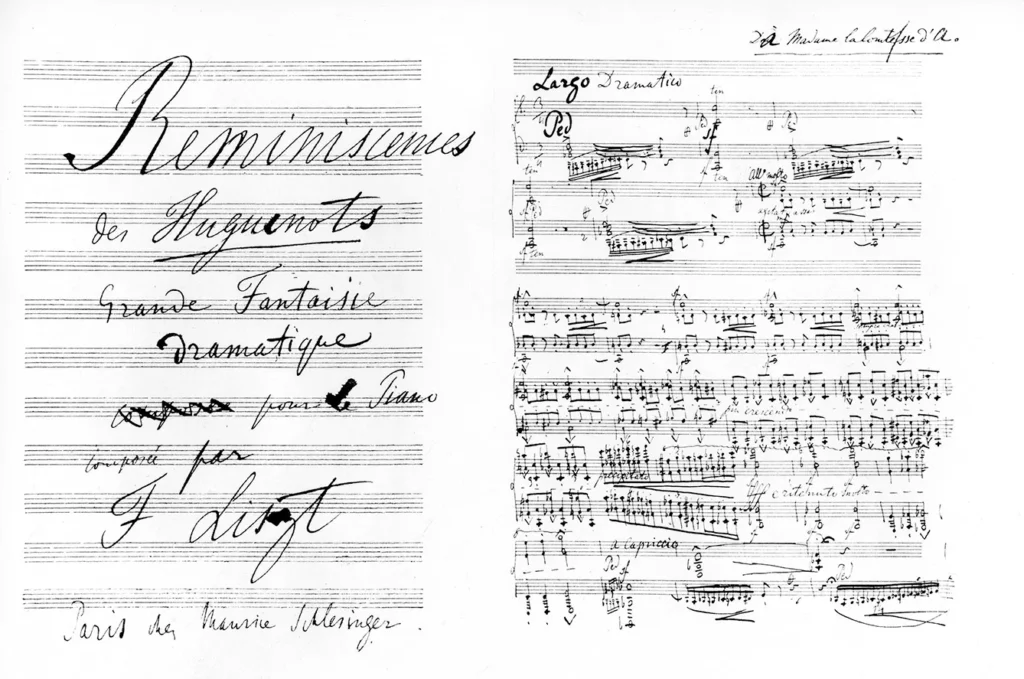

Another great musician and a contemporary of Liszt, Schumann, once remarked that it would be possible to find perhaps ten, maybe twelve piano players capable of performing Liszt’s 12 Grandes Études. But where did he draw inspiration from? Of course, Liszt wrote many completely original pieces, but during his concerts and as part of his music-writing, he would often draw from other great composers, rearrange their music, put different pieces together, draw a theme and… arrive at a masterpiece. Such is the case with one of the hardest pieces for piano ever written – List’s La Campanella, built around a theme drawn from Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in B Minor.

Plagiarism or remixes?

The truth is, composing savoir vivre was different in those days, and some composers were simply allowed a little more, especially when arriving at such brilliant pieces as Liszt did. Besides, Liszt wrote a plentitude of entirely original pieces. He even fathered a whole new genre altogether.

Liszt, fascinated with the works of Romantic writers, and in general, with literature and art, arrived at a genre that came to be known as Symphonic Poems. In his life, he wrote 13 of them and shook the foundations of the conservative musical world. How? Well, purists, such as Johaness Brahms (who famously criticized Liszt’s Dante Symphony, labeling it as ‘not music,’ and that was one of the nicest things he had to say about it) wanted to keep the world of music separate from the other arts. In contrast, the sole idea behind the Symphonic Poem was to translate another piece of art (literature, picture) into music. This marrying of the arts was unthinkable back in the day, but Liszt’s relentlessness in developing this genre inspired followers, such as the famous Antonín Dvořák.

A philanthropist with a broken heart

Despite his flamboyant stage persona, worthy of Mozart’s optimism and carefree attitude, Liszt believed that artists were called to do more and gave much of what he earned to charity. He famously conducted concerts in support of the victims of the Danube flood in 1839, thus bringing charity events to a form we are familiar with even today. Labeled a ladies man, he actually did fall in love and had deep, meaningful relationships, which both ended prematurely and broke his heart. He was also a patron of talented musicians in need and a pro-bono teacher who tutored many great pianists.

Liszt was not interested in creating copies of his style – instead, he believed in preserving his pupils’ artistic expression and intact talents – an attitude that showed generosity and empathy. Tired of his earlier popularity, Liszt sought consolation in his Christian religion in later life. He died in 1886, at 74, of pneumonia. His music, however, lives on, as does his fame as one of the greatest pianists (if not the greatest pianist) of all time.

And if you are not sure whether you have heard any of his pieces, then we want to assure you you must have, at least as a child. Which is one of the most famous performances of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2? The one by Tom and Jerry, of course. With a bit of a Tom and Jerry twist.