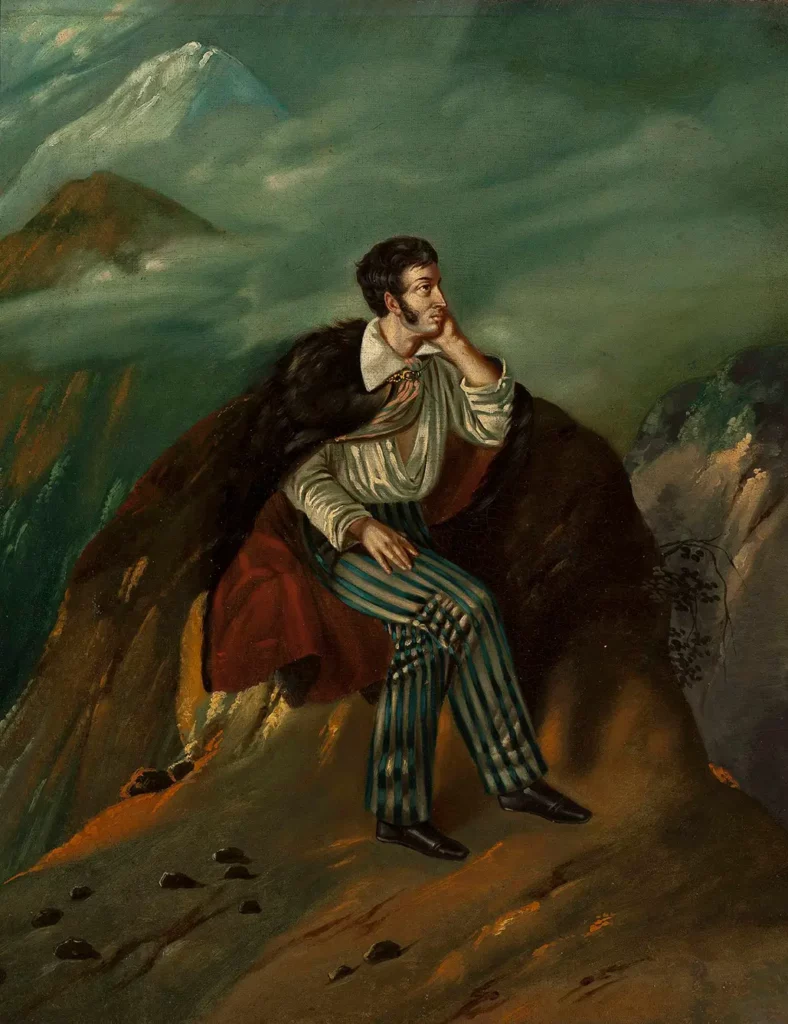

The usually overlooked fact about Romanticism is that it was not only a period in art but also a national project: poets and painters collected folk traditions and language to compile them into treasuries. Take the German Brothers Grimm and Slovak L’udovit Štúr as a reference. In the case of Poland, Adam Mickiewicz was perhaps THE most notable Polish artist of the period.

And his major work – the epic novel Pan Tadeusz (Sir Tadeusz) – is mostly a nostalgic account of life in the Polish countryside before it took a sharp turn after Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth fell to neighboring empires at the end of the 18th century.

Written in 1839 in Paris by a then-political emigré, the epic tells the story of the 1812 Napoleonic invasion of Russia, during which Poles were allied with the French against their oppressor (aka Russia). Set in a Lithuanian noble manor (Polish and Lithuanian nobility shared the same culture for centuries, with Polish as the lingua franca), the Polish support to the French war, which was technically an uprising, was a (failed) attempt at regaining independence and restoring the old world.

Ghosts of the food past

As the hopes were dashed, Mickiewicz decided to describe the passing world he experienced as a teenager. Along with romantic and political plots, the 9714 lines of poetry divide a few-days-long storyline into twelve parts and are filled with nostalgic descriptions of nature and lifestyle in the Polish and Lithuanian Commonwealth. It turns out that food constituted a vital part of this poetic description.

So, is Polish culture all about food? This ain’t right, but this ain’t wrong. Food is not only an everyday staple and a basis for festivities. The Polish economy was focused on food exports, and farming was a way of life. It merged with the dominating Christianity into an easily digestible symbolic order where the fruit of the land became a sign of God’s grace.

Food was also, sometimes literally, a way of communication, as in the case of czernina or czarna polewka, which literally translates as black soup. Made from duck blood, when served to a young man asking to marry a girl, it was a sign of rejection by her parents. Spoiler alert: this soup is also served in Pan Tadeusz.

The Pan Tadeusz menu

Among these twelve Episodes, we find descriptions of:

- Mushroom foraging. A Polish custom even today (most forests are public and free to forage), it used to be a social occasion;

- Hunting scene. As for manor inhabitants, hunting was both a social occasion and a food source. The party would go to a forest with bigos (cabbage stew), ready to be consumed during the sport;

- The coffee serving scene, with dedicated servants creating artwork using foamy milk, cream, and black brew;

- Breakfast, with beer and curd soup (yup!);

- Game grilled over a live fire;

- One of the protagonists steals good groats to feed them to the geese. The groats were reserved for rosół (meat bouillon);

- Actual bouillon, cooked with a coin and a few pearls – to improve health benefits;

- The saddening modern habit of switching Hungarian wine to Champagne and other inferior varieties;

- No less than two actual feasts: a “regular” feast and a wedding reception;

- Dining with the dead during Dziady (Forefathers’ Night), the Slavic Halloween ceremony;

- Ceremonial lunch with vodka and chłodnik, a chilled Lithuanian beetroot soup;

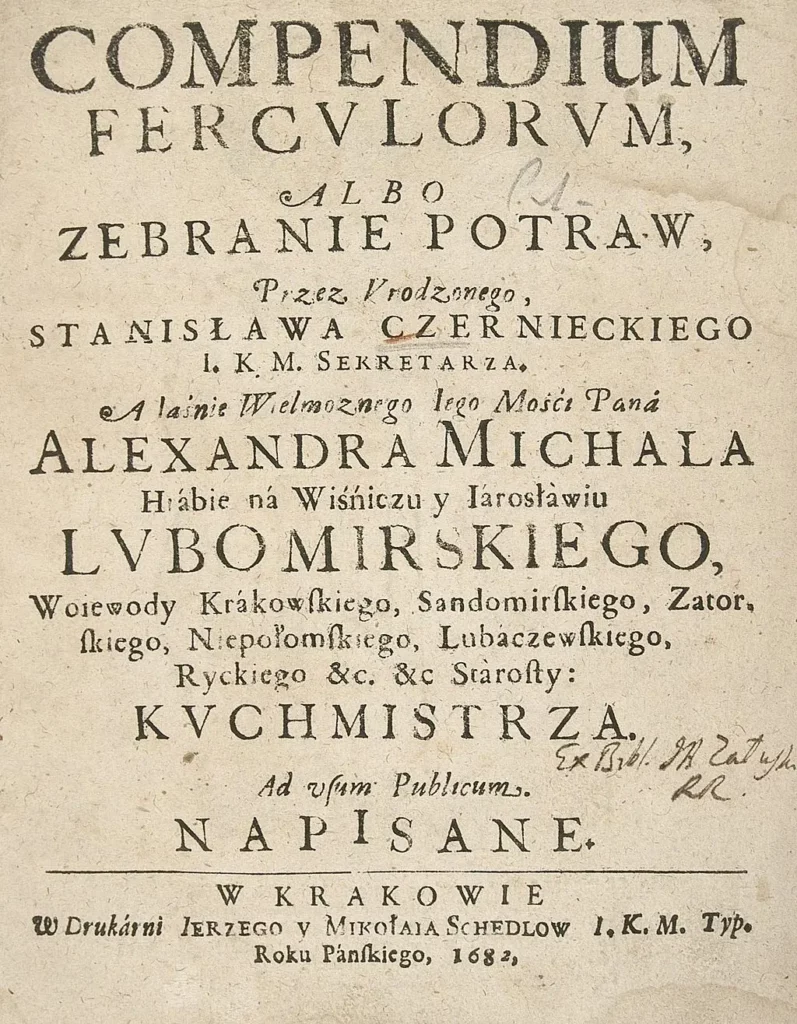

- Famous cookbook including recipes by prominent historical figures (historic in terms of the early 19th century – kings, princes, and popes);

- And, last but not least, one specific “foodstuff.” It’s a cheese mixed with… human brains. As Mickiewicz describes it, cheese was matured in elevated boxes in the garden that were accessed by a ladder. At one point, there’s a battle with Russian soldiers, and the Polish uprisers develop a clever tactic. You probably get the idea by now.

Those thirteen are not even close to exhausting the list of descriptions of dining, snacking, or other occasions mentioning a particular food or drink. Basically, Polish-Lithuanian nobility used food and acts of communal eating to wage wars, make peace, argue, come to terms, express joy, express sadness, celebrate both sad and joyful occasions, and communicate their decisions. And also for no particular reason.

It’s safe to say that each of the twelve parts of Pan Tadeusz contains at least one extensive description of the act of gathering foodstuff and eating. It’s clear that – except for warcraft and actual fighting scenes, varying from duels to regular military fighting – the epic poem is all about food.

Not to jump to hasty conclusions, but just take note: two centuries later, Mickiewicz’s narrative is still considered the most important account of early modern Polish-Lithuanian noble culture…