If you happen to visit a Viennese museum called Upper Belvedere, you may wonder if it’s an ancient gallery or a very modern one. The Upper Belvedere, one of two palace buildings facing each other in Vienna’s third district, is home to the largest collection of busts by Baroque artist Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. And we can assure you that these unusual sculptures are examples of early modern art, not contemporary art.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt enters the stage

Still, it may be a bit hard to believe. While the commonsensical understanding of Renaissance and Baroque art is that it’s white, classicist, serious, and generally orderly, the large part of Messerschmidt’s oeuvre is anything but. This is probably due to his mental illness: in a very modern way, the sculptor used his altered states of mind as a source of inspiration and a medium of relief. Wait, what year was it again? 1955?

No, it wasn’t. Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, born in Germany in 1736, set out for Austria to study arts and found work at the imperial arms collection designing busts. Talented as he was, he soon moved over to actual artistic sculpture, getting commissions from nobles of the empire and taking study tours to Italy.

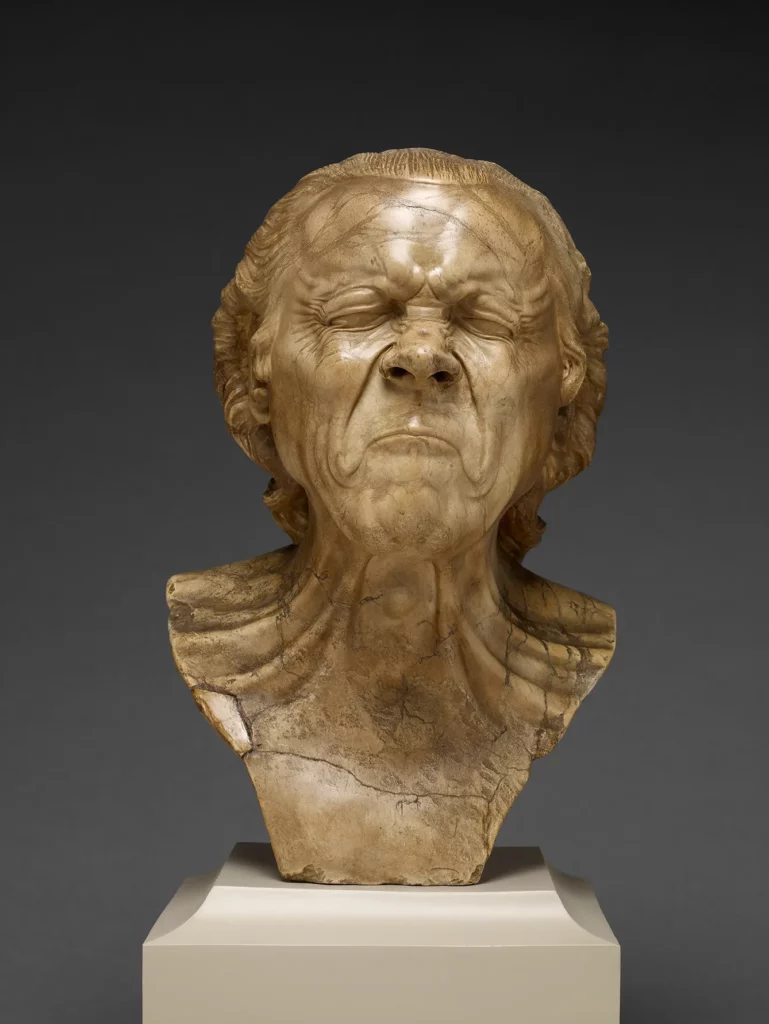

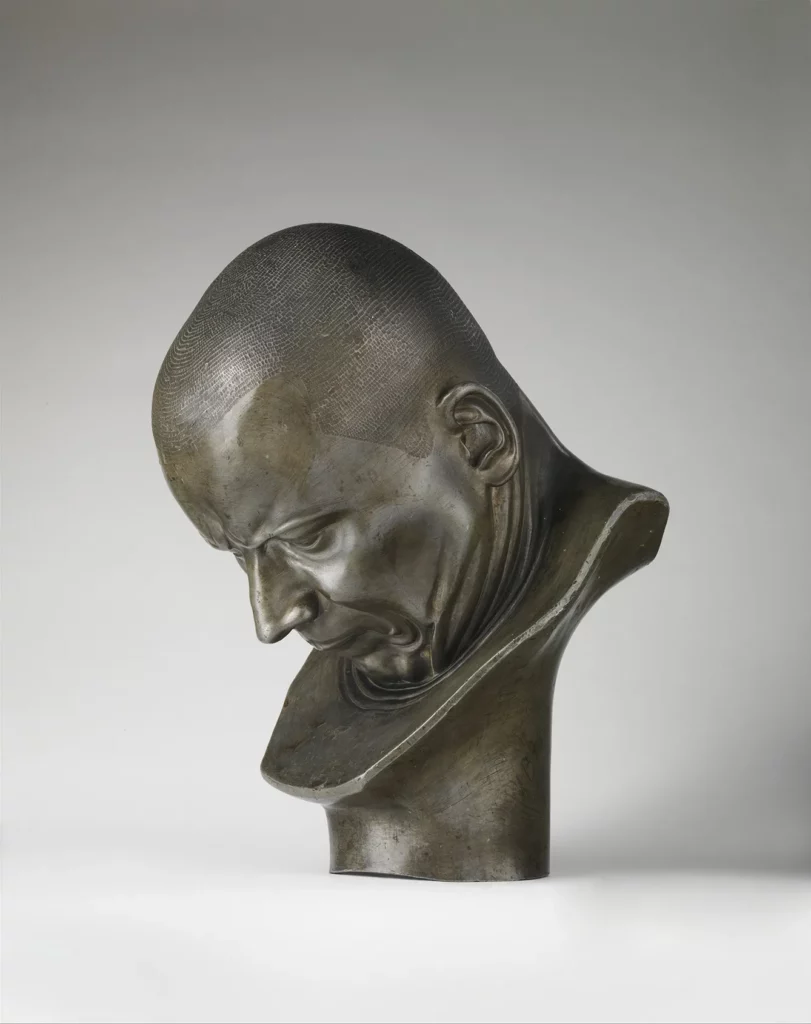

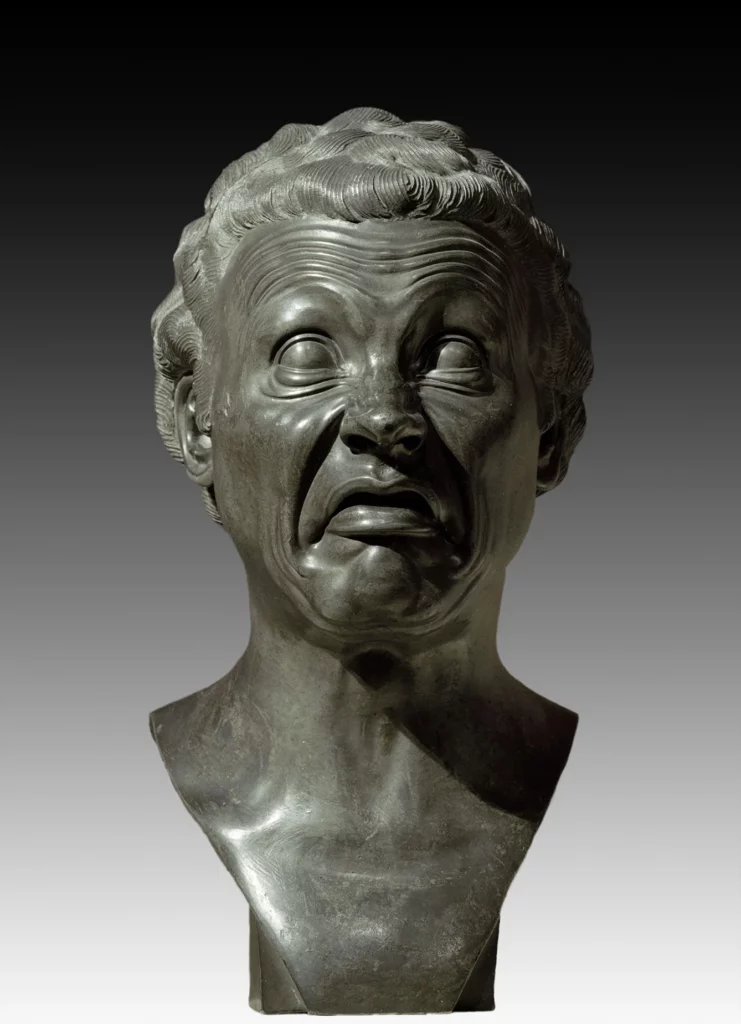

In the 1770s, when Messerschmidt was in his mid-30s, he took up his unusual and most distinctive project – Kopfstücke (Eng. head pieces, known as Character Heads) – distinctive faces showing distorted expressions that, at the time, were not commonplace in art. As his life is well documented, we know that he planned for the series to be of hundred pieces, but over the next decade – until he died in 1783, he managed to create two-thirds of this number. (*Some researchers suggest that the collection may be as well complete, as 66 was a target number of actual Character Heads, and the sculptor made some spin-offs.)

Character Heads: the many faces of a sculptor

Pain, laughter, sadness, resignation, scream, disgust – even constipation. While today exploring different states of mind is not unusual in art (think Francis Bacon, or Bill Viola’s slow-motion video clips), in Messerschmidt’s times, it was only occasionally an art theme. The closest kinship to this 18th-century Austrian might be the 17th-century Italian Caravaggio with his “Boy Bitten by a Lizard.” Alas, in this case, another similarity would be the image of a troubled artist behind such work.

To this day, hypotheses regarding what troubled the sculptor are unsolved. Perhaps these were depressive or psychotic episodes, or perhaps schizophrenia. One more idea points to a friend, or at least an acquaintance, Franz Anton Mesmer. This German physician focused on the research of “animal magnetism,” an effort to explore an interconnection of medicine and development in physics and astronomy of the time. His treatment procedure was based on finger pressure on the patient’s body, which resulted in their reactions – which Messerschmidt possibly studied as a witness.

Bratislava, the asylum

Paranoid, schizophrenic, or simply eccentric, Franz Xaver was definitely not sane. In the year 1777, he was forced to move to Bratislava, back then known as Pressburg. Now the capital of Slovakia, the city is just over 50 kilometers away. There, he stayed with his brother – being unable, for psychiatric reasons, to continue his successful career in Vienna.

His work back then was obsessive – in 1780, the artist bought his own house, where he stayed lonely, still shrouded by the myth of the brilliant sculptor. A few years later, in 1783, he died – probably of pneumonia. In the late 19th century, his oeuvre – including 49 of the Character Heads – was cataloged, and the work is on display in Vienna, as well as Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava, and in the Louvre.

He’s not in the premier league in the Artists’ Hall of Fame, though. It is a pity, as, for all the wrong reasons of insanity, his work remains proof positive that not all early modern art is just boring guys with serious faces.