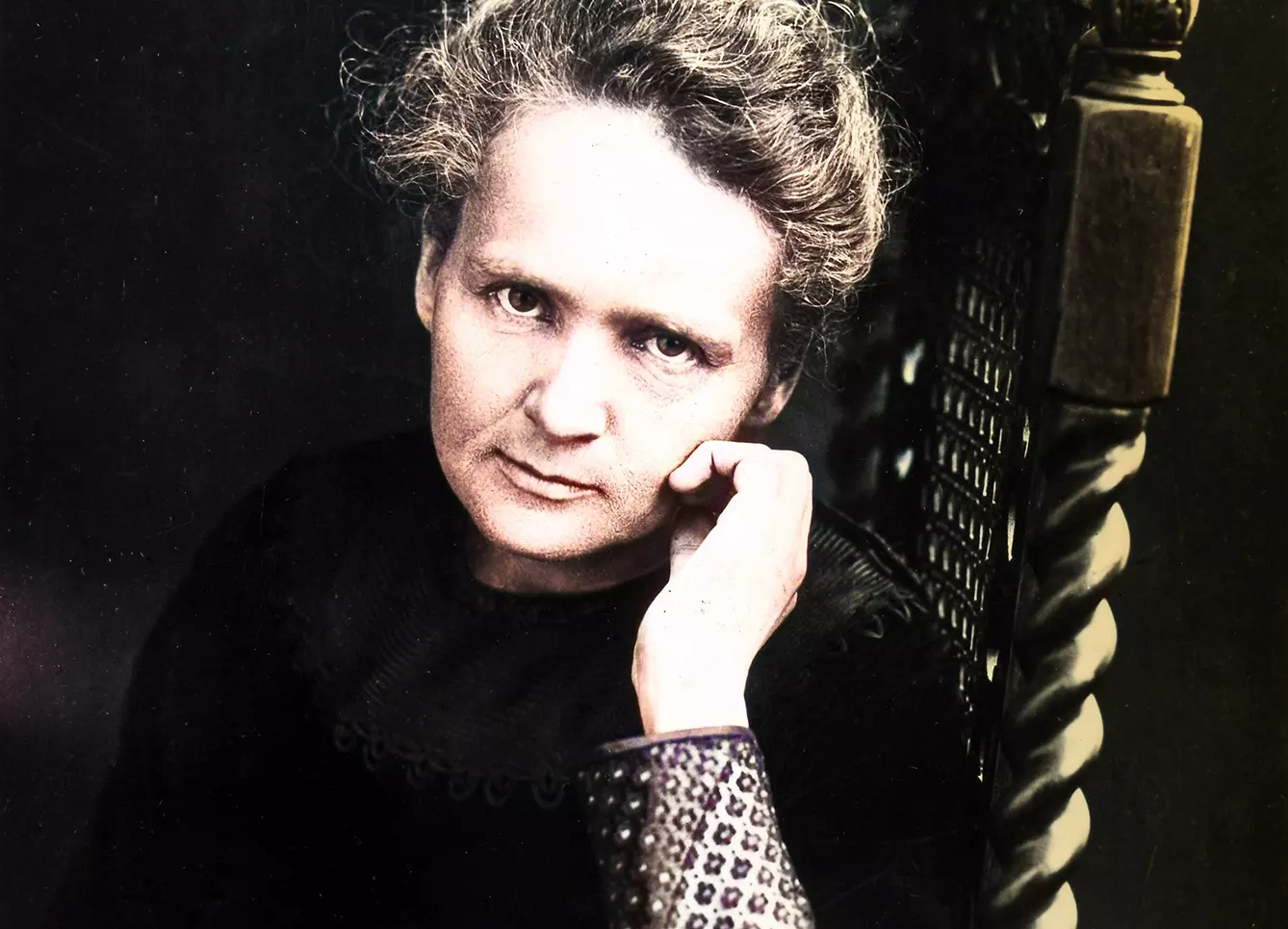

A female scientist who thrived in the uber-masculine 19th-century world of science, one of only a handful of people to be awarded the Nobel Prize twice, and a symbol of success, scientific genius, and the emancipation of women. This description is enough to ensure her position as an icon for generations of women (and men!) to come, but Marie Skłodowska-Curie was, unbelievably, so much more than this.

Marie Curie: two Nobel prizes for woman

Marie (pol. Maria) Curie, whose maiden surname – Skłodowska – is too often skipped over, left for Paris when she was 24 to take up studies at La Sorbonne. This is where most biographies of her begin, culminating with her later discovery of radium and polonium and her two Nobel Prizes – one in physics in 1903, the other in chemistry in 1911. But she didn’t become a genius phenomenon overnight, so her early years must have been equally interesting, right?

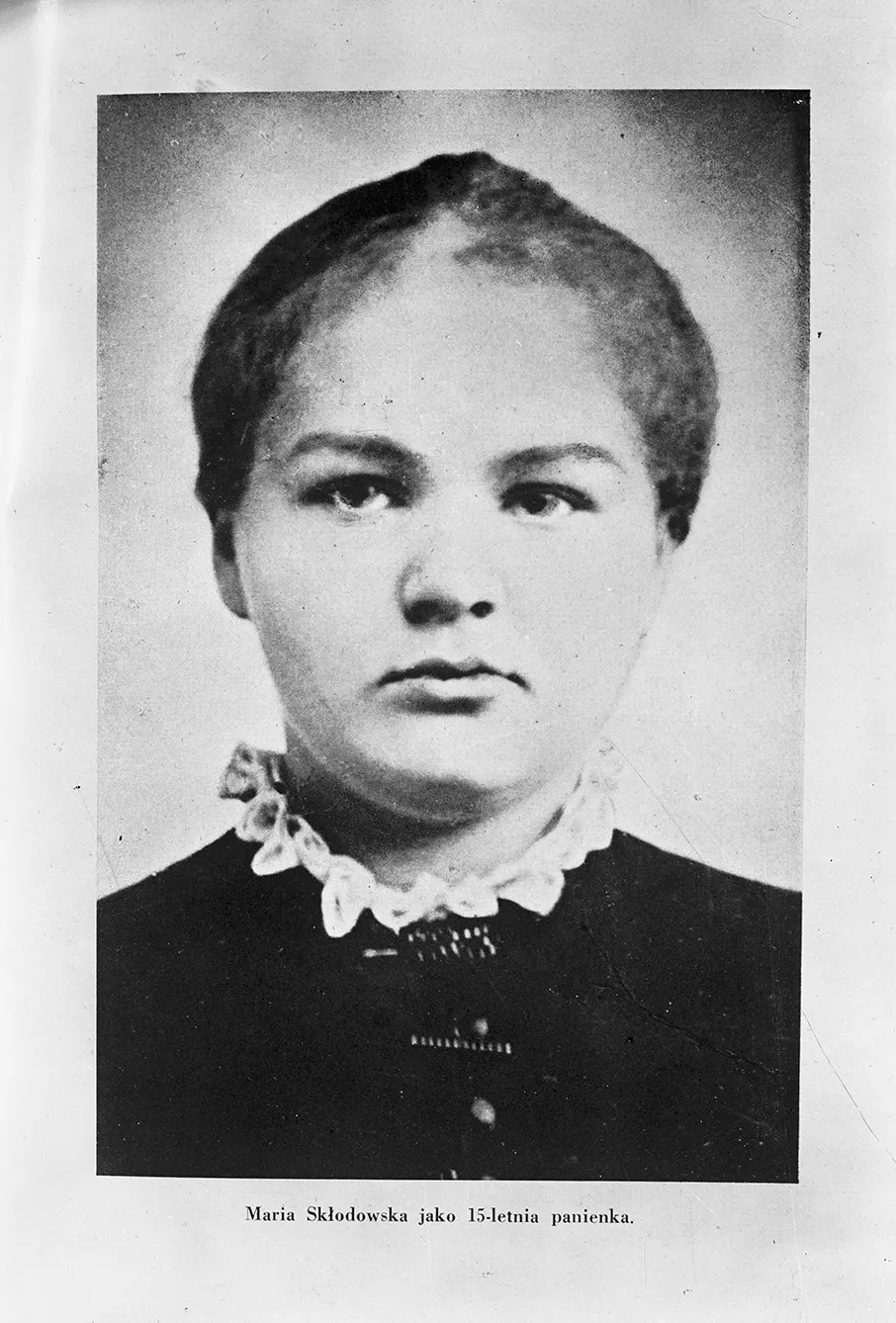

As a matter of fact, they were. Skłodowska was born in somewhat politically complicated times in Warsaw in 1867. Throughout the 19th century, almost all of the territory of modern-day Poland was controlled by an array of political entities – with the exception of some tiny enclaves small enough to be safely granted independence. Warsaw was the capital of what was called the Kingdom of Poland, but which was, in fact, part of the Russian Empire province. The entire history of 19th-century Poland is told through Russian and German efforts to integrate parts of Poland into their countries, combined with acts of Polish resistance.

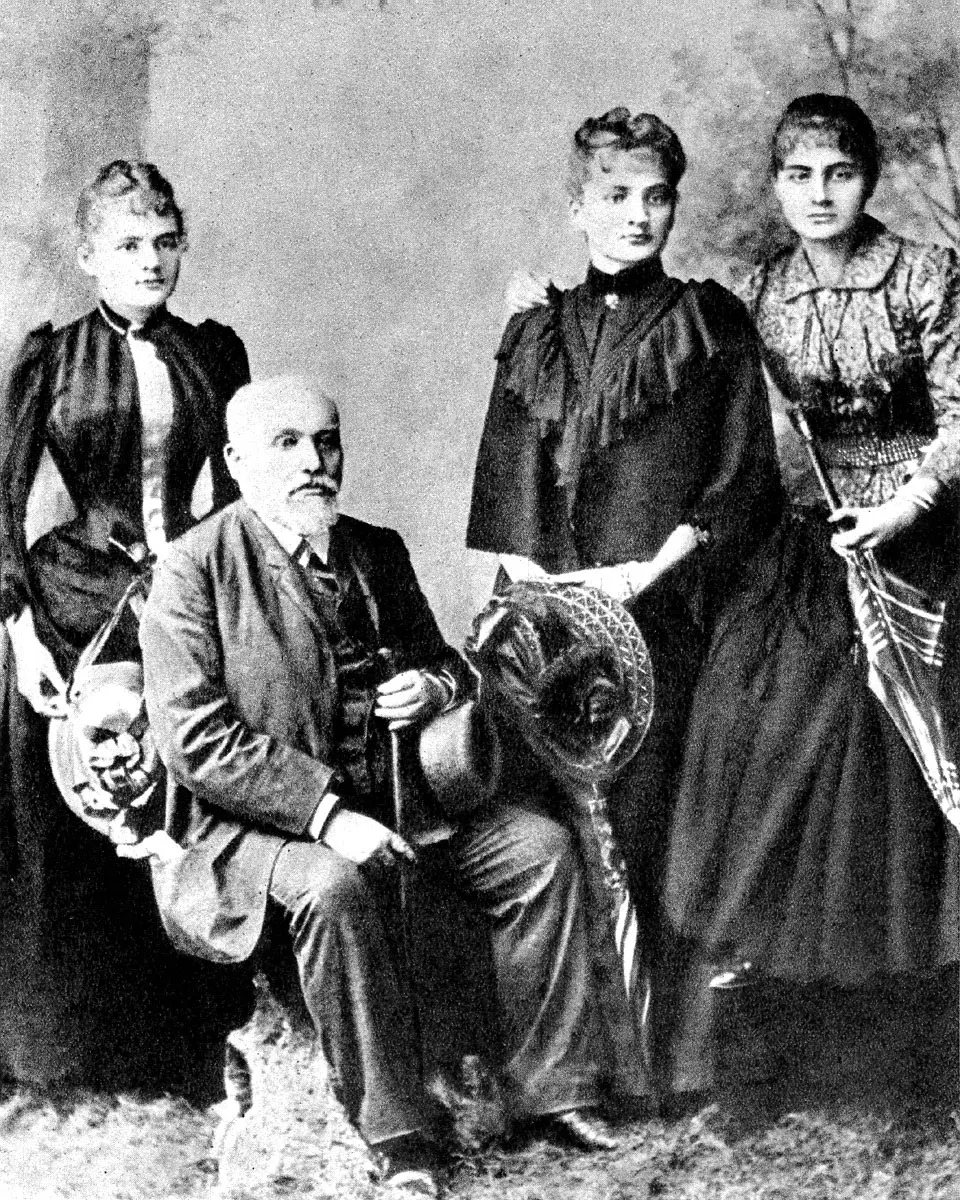

The youngest child of a Polish family in the lower aristocracy, she was raised atheist, contrary to contemporary religious customs. Both she and her sister, Bronisława, developed interests in science; however, this was a difficult path in those days due to tsarist rules against educating Polish women. Since they could not study in Poland, it was, therefore, necessary that they go elsewhere, which created financial challenges.

Scientific pact

So Maria and Bronisława made a pact. Under the terms of their agreement, Bronisława would leave for Paris to take up studies – and the younger Maria would work in Poland to support her sister and pay for her education. Then, once Bronisława had finished her studies and could afford to support Maria’s studies in Paris, the younger sister would have her turn to further her education.

The first years of Skłodowska-Curie’s career were spent as a private teacher working for aristocratic families and sending money to Paris. But she did more than that – in her spare time, she also taught Polish to children in villages, an act that was forbidden and prosecuted by the Russian administration.

Polish intelligentsia encouraged these acts of rebellion, as teaching peasant children in Poland was not only meant to level the educational gap in societal classes but was also a necessary step in raising national awareness to ensure a thriving nation. Called “work at the foundations,” it was the primary form of political activism in the Kingdom of Poland.

After almost getting married in Poland, she returned to her secret education, and this is how she came to know the foundations of chemistry. Then finally, in 1890, Bronisława announced that she was now ready to provide hospitality for Maria in Paris. And now, we have arrived at the point where the story of Maria Skłodowska-Curie usually begins.