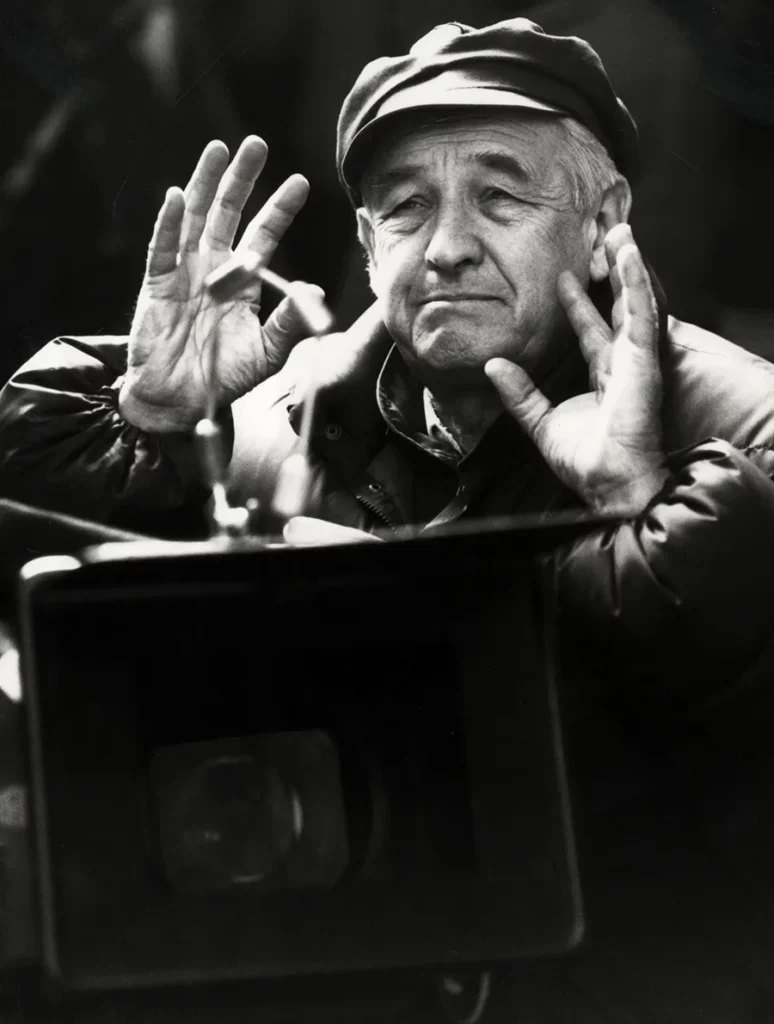

Let us get things straight first. Perhaps the world-acclaimed director Martin Scorsese is not really skilled in pronouncing Łódź (Wootch is the closest, but not perfect) – but that doesn’t diminish his admiration for the Polish city bearing that name. Or rather what it represents – as the city, sometimes nicknamed Hollywoodź, is the center of Polish cinema, and Scorsese is known as one of the most prominent advocates for the actual art of the movies, not only the entertainment business.

These are perhaps the two stances that have been in an ongoing debate for the last few decades. There are movie creators engaged in deep, intimate, and intricate stories, and there are businessmen carving ever more visually stunning blockbusters. Only the former sometimes succeeded among both groups – but it was not always that way. Because what Scorsese admires the most (and many others with him) is a glorious past known as the golden age of Polish cinema and its modern legacy.

Polish Film School

Take a deeper dive into our website, and you’ll clearly see that the socialist period timeline is divided into periods – the golden era and the iron era, the terrors and the thaws, the prosperity and the despair. This is to some part because the more authoritarian the rule, the more important who the authority is, as well as some economic background.

“I cannot explain how your cinema from Wajda, Polański, to Skolimowski, the whole lot – influenced my cinematic output. But it still does. At some point, I realized that when I wanted to make actors or cinematographers understand something. I show them Polish films from the 1950s,” said Scorsese in 2011, having received an honorary doctorate from the Łódź Film School. It was this period, the 1950s, that gave birth to the success of Polish movies.

The period is called the Polish Film School and, though unofficial, was quite formal and distinctive. Rising stars of Polish cinema debuted in the late 1950s. Among them was Wojciech Has, Andrzej Wajda, Kazimierz Kutz, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, and Krzysztof Zanussi. Influenced by Italian neorealists, they were a bit freer than the filmmakers of the previous eras to speak up through their movies since freedom of speech got partially allowed in Polish social life in 1956. And there was a space to use it. The war memories were still fresh, and the ethical questions raised in turbulent times demanded answers in the form of art.

Moving past the war

By the mid-sixties, the success of the Polish Film School made Poles a cinema-loving nation, but the war-related topics were already worn-out. The situation could go many ways, but luckily some important figures entered the stage. They were not artists, though – they were politicians, namely the Minister for Culture Józef Tejchma and his deputy in charge of cinema Mieczysław Wojtczak.

Especially the latter was, to cinema’s luck, far from the stereotype of a dull and stubborn bureaucrat. Thanks to the skillful patronage of the ministry over the film industry, the Polish experience in intimate and tasteful black-and-white narratives could meet a huge budget and support for large-scale productions.

“Faraon” (“Pharaoh”) and “Potop” (“The Deluge”) remain stunningly magnificent blockbusters of historic cinema, the former being a story from Ancient Egypt adopted to screen after Polish 19-century writer Bolesław Prus, the latter – by his peer Henryk Sienkiewicz, telling the story set in 17th-century Polish-Swedish war.

This was when state propaganda needed to allow another stunning giant production of “Krzyżacy” (“The Teutonic Knights”), again by Sienkiewicz (an anti-German narrative set in medieval Poland), while Wojciech Jerzy Has has taken a sophisticated and successful attempt at “The Saragossa Manuscript,” the puzzling story written in the late 18th century in French by a Polish-French aristocrat Jan Potocki.

Cinema of Moral Anxiety

These successes only made the appetites grow, and another “Polish School” appeared in cinema history, dubbed “the cinema of moral anxiety.” Agnieszka Holland and Krzysztof Zanussi, along with the world-famous Krzysztof Kieślowski, entered the scene. Andrzej Wajda was perhaps at his best with “Man of Marble,” and “moral anxiety” was under scrutiny by Feliks Falk or Filip Bajon.

The titular anxiety (or “moral unrest,” as it is also translated) is a new approach to the human condition in relation to their time and role in society. The Communist regime is portrayed in decay, and the focus is on an intimate moral struggle, especially against a backdrop of everyday life under communism.

When in 1981 the martial law was introduced in Poland to facilitate the communist fight against popular movement, this sequence of “schools” came to an end. The 1980s, and especially the newly introduced capitalism of the 1990s, was for Polish cinema a time to look for new ways of showing reality. “Ida,” the Academy Award winner of 2016, is labeled as an effort to recreate the vibe of the Polish Film School.

Your Watchlist

If there was one thing great Polish movies lacked, it was possibly the imaging quality, or sometimes even more mundane thing – the means to make them available. This is where Martin Scorsese enters the stage. While in Poland in 2011, Scorsese took an interest in the process of digital restoration of the pearls and facilitated contact with the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

In 2014, in the organization’s New York cinema, the festival presented over twenty titles from Polish cinematheque, from 1957 “Eroica” by Andrzej Munk to 1988 “A Short Film About Killing” by Krzysztof Kieślowski. The following year, the same festival was set in Great Britain.

If you want to get to know Polish cinema masterpieces, and you should, why don’t you try Scorsese’s advice? Here’s the list:

- Eroica (Eroica, Andrzej Munk, 1957)

- The Last Day of Summer (Ostatni dzień lata, Tadeusz Konwicki, 1958)

- Ashes and Diamonds (Popiół i diament, Andrzej Wajda, 1958)

- Pociąg (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1959)

- Knights of the Teutonic Order (Krzyżacy, Aleksander Ford, 1960)

- Innocent Sorcerers (Niewinni czarodzieje, Andrzej Wajda 1960)

- Mather Joan of the Angels (Matka Joanna od Aniołów, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1961)

- Knife in the Water (Nóż w wodzie, Roman Polański, 1962)

- The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie, Wojciech Jerzy Has, 1964)

- Salto (Tadeusz Konwicki, 1965)

- Walkover (Walkower, Jerzy Skolimowski, 1965)

- Pharaoh (Faraon, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966)

- Trzeba zabić tę miłość (Janusz Morgenstern, 1972)

- Wesele (Andrzej Wajda, 1973)

- The Illumination (Iluminacja, Krzysztof Zanussi, 1973)

- The Hourglass Sanatorium (Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą, Wojciech Jerzy Has, 1973)

- The Promised Land (Ziemia obiecana, Andrzej Wajda, 1974)

- Camouflage (Barwy ochronne, Krzysztof Zanussi, 1976)

- Provincial Actors (Aktorzy prowincjonalni, Agnieszka Holland, 1979)

- The Constant Factor (Constans, Krzysztof Zanussi, 1980)

- Man of Iron (Człowiek z żelaza, Andrzej Wajda, 1981)

- Austeria (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1982)

- Blind Chance (Przypadek, Krzysztof Kieślowski, 1987)

- A Short Film About Killing (Krótki film o zabijaniu, Krzysztof Kieślowski, 1988)