“Light a candle to God but spare the stub for the Devil” is an old Polish proverb with roots in cultural politics. The devil here is not the Christian Antichrist but rather a handy description of the pagan gods of Lithuania, the last pagan country in Europe, which turned to Christianity in its western edition.

Princess married to the “Devil”

But, along with (as Christians claim) the opportunity to be salvaged, Lithuanian Prince Jogaila also gained a wife, who happened to be the heir to the Polish crown as a successor to the original Polish Piast Dynasty. This marriage in 1386 established more than just a personal union – it created an alliance between the two countries. And this was the first step toward their unification.

Or, more than two, mind you, as what was then-called Lithuania was far more extensive than today’s nation-state of this name. With Russia being only a stub, Poland oriented toward the west and south, and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had a lot of space to develop.

The countries shared a common enemy – the Teutonic Knights Order, which had its own state and capital in Malbork and Vilnius at different stages of its medieval history and controlled parts of – or in some cases the entirety of – what is now Latvia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: the Central European empire

It had access to the Black Sea and shared a border with the Crimean Khanate in the south. To the east, on a bright day, you could see Moscow from the Lithuanian frontier keeps. And Minsk and Kyiv, now capitals of Belarus and Ukraine, respectively, were deep inside the Lithuanian Territory.

On the other hand, Poland hardly reached the Baltic Sea, separated from it by the Teutonic Knights, and today Polish Silesia was a part of Czechia. But it stretched much further to the South, and through Moldovan seigniory, it also reached the Black Sea.

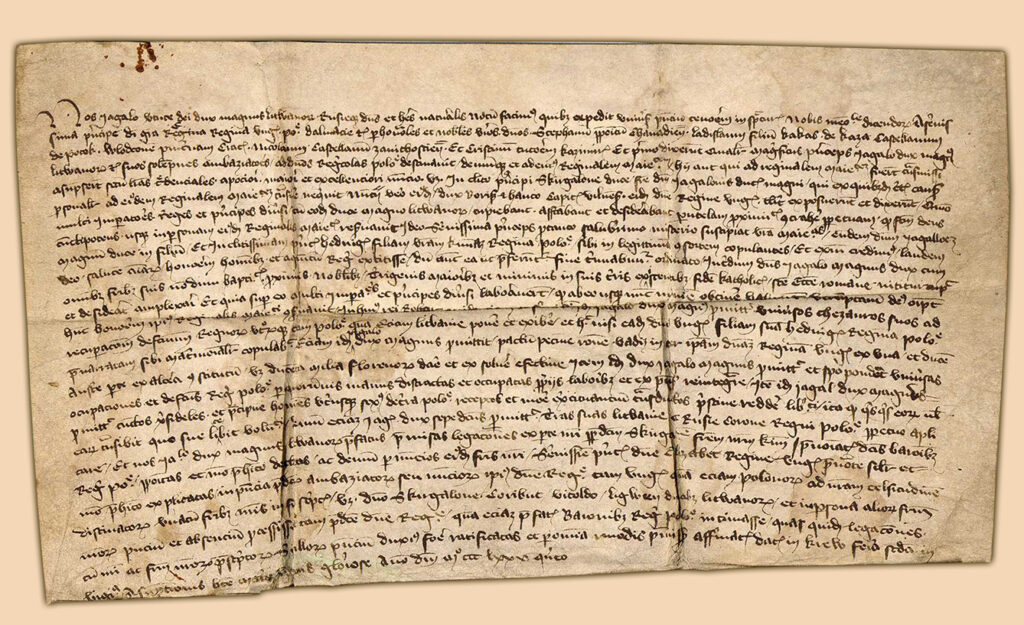

The act of the Union, signed in 1385 in Lithuanian Kreva, contained the clause that both countries were to be merged in perpetuity. Not yet a single political entity, from then on, both countries were on course to become Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

And it happened, but no earlier than two centuries later, upon the signing of the Union of Lublin in 1569. Needless to say, a lot happened during those two centuries. Both countries were stronger in their internal politics. Their stability improved after the defeat of the Teutonic Order State in a series of wars in the 15th century. To afford the war, the Polish king granted its nobility a vast register of privileges, subject of envy for their Lithuanian counterparts.

1569: The year the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was born

When another Polish dynasty, established by Jogaila and his Polish wife Jadwiga (Hedwig) and called the Jagiellonian, was set to expire, the last king of this name hastened the preparations.

The treaty effectively creating the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was voted in 1569, effective from July 1st. This is when two countries, still nominally separate, became one in practice. Both had a parliament in common, as well as a monetary system. Its unified foreign policy meant using both armies to benefit the partners, though the troops themselves remained separate.

And there remained no question of the head of the country, as the nobility of the whole new country voted for a king, effectively establishing “noble democracy” – with an equal vote for each person with nobility granted. It’s worth noting that “nobility” in Commonwealth could mean, on average, a whopping ten percent of the population, much more in the case of particular regions. Those varied widely regarding economic status but were equal in civil rights. Among them was a freedom of religion – quite unique in early modern Europe.

This created one of the biggest political entities of its time and region. The period from the Union of Lublin to mid-17 c. is described as the “Golden Age” of the country, with its largest territorial extent, famously a million km sq, in the first decades of the latter. Polish-Lithuanian soldiers are the only ones to ever occupy Muscovite Kremlin, as commemorated by the Russian official calendar to this day.

The Baltic domination

As both Christianity and perhaps more sophisticated law and administration came from Poland, its language became in practical use in the whole Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. (*Lithuanian, reborn in 19 century, is therefore based on very archaic remnants and, as such, closest than any to Sanskrit.)

The decline of the country came only later. In the late 17c., wars of domination in the Baltic region, Muscovite ambitions, and civil unrest in the southeastern Commonwealth, now Ukraine, known as Cossack uprisings, shook the foundations of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Later, when the age of empires truly came with the trend known as “enlighten absolutism,” the early modern empire failed to modernize and was gradually devoured by the Habsburg Empire and the newly created Prussia and Russian Empire. As commons interpretation has it, what didn’t help was the notion that remaining a weak country with soft power would prevent it from demise.

The effort to modernize in the form of the Constitution of May 3rd, 1792, was too little, too late. By 1795 the whole territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was partitioned between the three, and the Polish (or Polish-Lithuanian) culture took a sharp turn. Throughout the 19th century, it was shaped by the influence of three foreign cultures – and opposition to them led to clear contrasts between the regions.

When World War I sparked the recreation of nation-states in Central Europe, they came back in altogether different forms. The current countries of Poland, Baltic Countries, Belarus, and Ukraine, as well as Moldova and Slovakia, share culture, language remnants, and many parts of history, which have shaped the future. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth remains a geopolitical project that shaped the region.