Roman von Ungern-Sternberg’s life is complicated and full of adventures in such a way that he almost seems unreal. Maybe except that it would be hard to invent a guy who started as a Central European aristocrat and ended as a self-appointed army leader in Mongolia, all that not in some medieval times, but in the twentieth century when global geopolitical order was already in full swing.

The Crazy Baron von Ungern-Sternberg

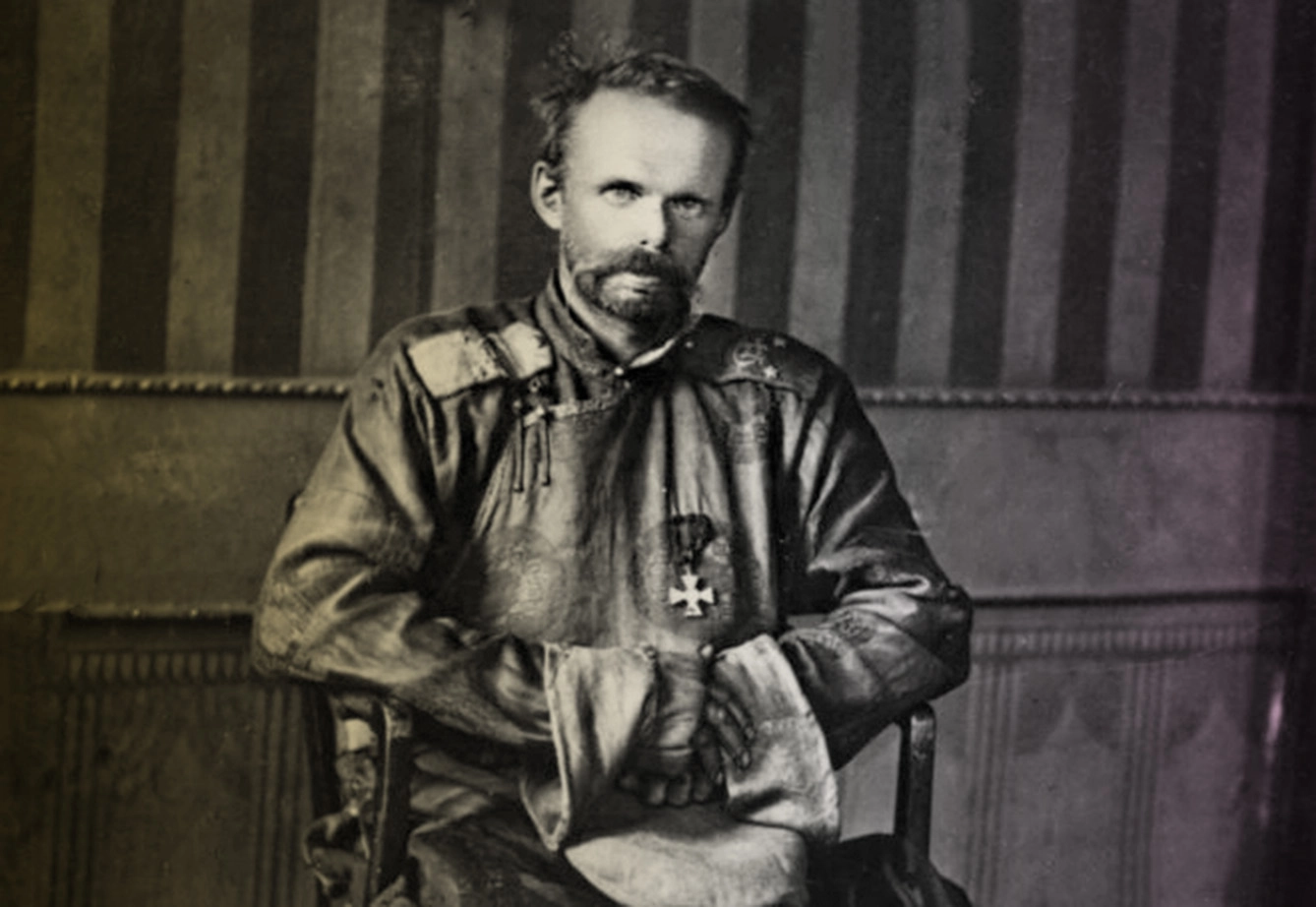

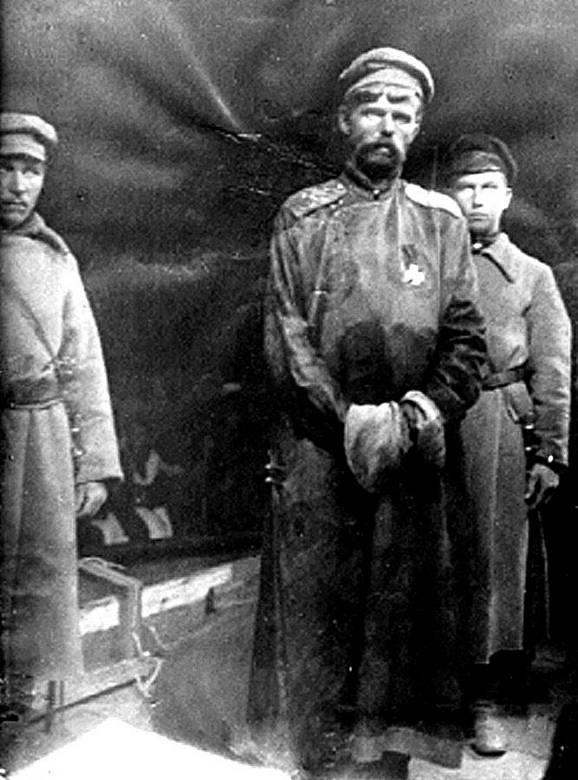

By the time “The Crazy Baron,” as he was called, was captured by the Soviets in August 1921, he made it to the self-appointed commander of the Asian Cavalry Division and a Buddhist. Two weeks later, he was tried for just six hours and executed on the same day in Novonikolayevsk, a city now known as Novosibirsk, by the red communists rising to power in former czarist Russia.

But to fully understand the list of charges that made a man with a German name persecuted by Russians in Mongolia, we have to go back in time. Perhaps it is best to start in Graz, where Roman von Ungern-Sternberg was born only 35 years prior, in 1886.

Although born in what is now a southeast Austrian city, Sternberg’s parents were Estonian Germans, as the Baltic countries were back then still under a strong influence of German culture introduced centuries earlier by German knightly orders. When he was six, his parents divorced, perhaps with his father’s mental illness in the background.

Roman’s mother took him back to Revel, now Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, and soon moved again to nearby Järvakandi, having remarried. Her eight-year-old didn’t accept his stepfather and was also a troubled student. He was still a misfit and conflicted with everyone in the Naval Academy in St. Petersburg, where he studied hard.

Mongolia, Buddhism, and beyond

Perhaps the Russia-Japanese war of 1905, where he fought on Russia’s side, introduced Buddhism to him – he was later known as a follower of the religion, which was unusual at the time and contributed to his reception as a misfit, though officially he remained a Christian Orthodox. After a few more personal conflicts, he got transferred to the czarist regiment stationed near the Chinese border in Russia’s far east.

A spy, a nomad, wandering soldier, after one of his duels marked with a distinctive and famous scar on his forehead, he traveled to and fro, sometimes in Estonia, but also learning yet another language, adding Mongolian to German, English, French, and Russian got in his multi-national upbringing. After another adventure – fight or duel with Chernivtsi, head of the city, he was imprisoned in this Ukrainian town.

We know a little about the whereabouts of Ungern-Sternberg between February and October 1917, when two subsequent revolutions in Russia – white and red – happened. But later, Ungern found himself again in Siberia and in contact with an important figure in the White Army, Grigory Semyonov, who commanded him to form an anti-Soviet military.

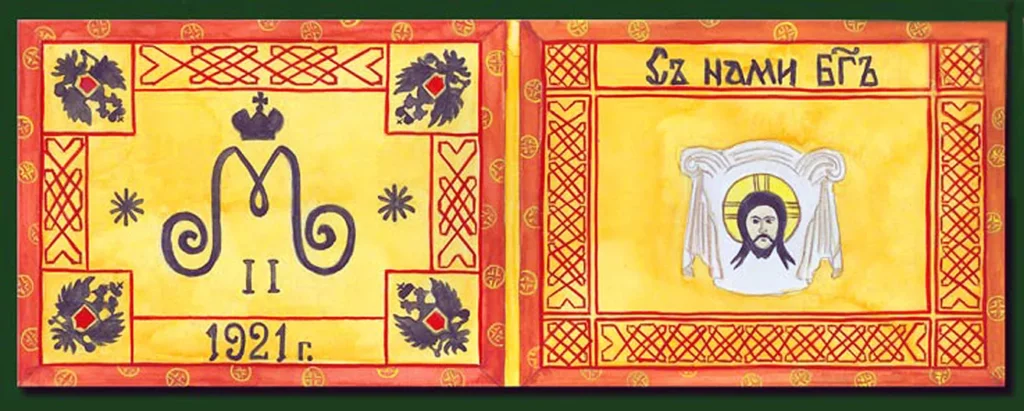

With support from the Chinese and Japanese, Roman von Ungern-Sternberg and his troops – varying in number from hundreds to thousands – succeeded in their subsequent battles against the Red Army. As an ally to the White, Sternberg was also supported by the European military. When his and Syemyonov’s power in Siberia became firm, Ungern made himself a kind of General Kurz from “Apocalypse Now,” relentlessly ruling his troops and exterminating the Red. He was part of a political project forming a nationalist-imperial country called Great Mongolia under the Japanese umbrella, but the project failed.

The spiritual leader

When Sternberg’s and Syemyonov’s ways parted after the failure of the White Army, Sternberg made another one of his own in Mongolia with former Semyonov’s cavalry. Perhaps growing mad or just illusioned by early 20th-century health ideas, he decided on eugenic ways of strengthening his army by eliminating weaker soldiers. He also based his military plans on fortune-telling.

Still, he was successful, and in early 1921 he conquered the city of Urga, which remained under his control for some time. He made some sensible reforms there but remained a warlord by nature. He also made it to quite a title – he became the Khan of independent and theocratic Mongolia and was considered to be the supposed incarnation of Bogd Gegeena, the top-ranked lama in Mongolia.

Half a year later, still leading wars in Mongolia and Siberia, he met the resistance of the nationalist movement, which made him fight on two fronts – with the other from the army of the Red Russian revolutionists. His last act before being captured was to try to retreat to Tibet, facing resistance, mutiny, and desertions of many of his soldiers who didn’t support this way of escape. Perhaps, if the Russians didn’t execute him, he’d have been a victim of one of the attempts on his life at that time.

Ungern’s fame remains his heritage – one large account written by Polish adventurer and writer Ferdynand Ossendowski and published as “Beasts, Men and Gods” as early as 1922. Some claim that von Ungern-Sternberg had a treasure and Ossendowski was instrumental in hiding it. Is that true? Reading about Sternberg’s and Ossendowski’s accounts, the only correct answer is: what is?