The opposition of strength and agility is one of the most common factors in every warfare, from David vs. Goliath to current military efforts. Medieval Europe, famous for heavy knights in plate armors, seemed to be on the heavy side. Among them were Teutonic Knights – a Christian order of German origin that established its own state in what is currently Northern Poland and the Baltic Countries.

Teutonic knights: Tartars to the rescue

The constant tensions on the border grew as the ever-expanding Teutonic state renewed hostilities against still-pagan Lithuania and its forming alliance with Christian Poland. While Poland itself had problems with Islamic Tartar intrusions in the south, back in their own country, the same military formations proved effective in fighting heavy cavalry.

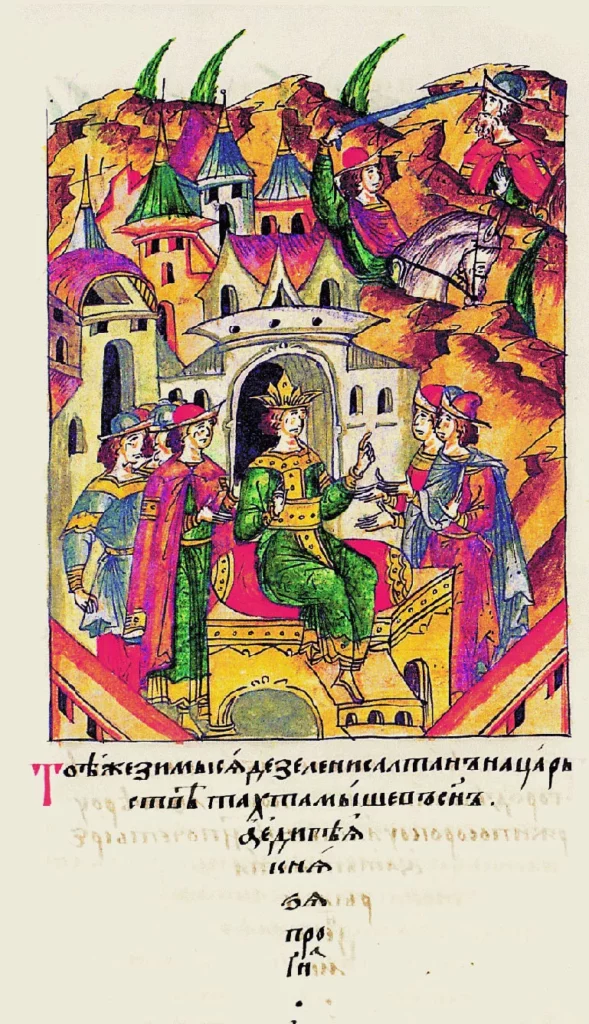

Mongolian tribes, highly skilled in horseback riding, archery, and a lasso-style weapon called arkans, had proved to be effective against knights as early as 1320. In the late 14th century, Tartars were no longer only allies of Lithuania but had also become settlers in the area. Welcoming different religions, Poland and Lithuania, whose partnership and later union formed in the period, granted them good living conditions.

Islamic soldiers in Kruszyniany

In Tartare’s own Golden Horde, a vast central Asian empire, political turmoil led to the constant influx of dissidents interested in finding a new space to live. Once settled in Lithuania, there were expected to serve as soldiers. They were also granted freedom of religion, some extent of autocracy, and recognition of their noble status.

The peak of the Polish-Lithuanian alliance with the Tartar was their part in one of the most significant medieval battles – Grunwald in 1410. The expelled Khan Cäläletdin (usually referred to in English as Jalal al-Din Khan ibn Tokhtamysh) of the Golden Horde fought against the Teutonic Knights, praying, “Allāhu Akbar!”. Legend has it that Teutonic Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen, who died in the battle, was killed by a Tartar soldier named Bahadura ad-Din.

The Tartar settlement in the northern part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth lasted until the 18th century. Some later moved back to the south, and some still lost part of their identity to assimilate with the neighbors. But in the recent census in Poland, some 2,000 people still declare Tartar nationality.

To get familiar with their unique culture, one only has to visit the villages of Lipniki and Kruszyniany in Poland. Known as the region of three feasts, you can witness Islamic prayers on Friday, Jewish prayers on Saturday, and Christian ones on Sundays. You can also still hear Muezzin proclaiming the daily devotion in Kruszyniany and visiting Tartare yurt.