The creativity of a good writer can prove challenging to translators. And not just in the sense of wordplay, puns, or double entendre. Take Tolkien’s Hobbiton, for one. It was supposed to resemble the English countryside while evoking a sense of comfort and familiarity. So translators have options. One is a direct, word-for-word translation to try to capture Tolkien’s story. Another is to opt for a more interpretive translation, focusing instead on capturing and evoking the same (assumed) sentiment and feeling for foreign language readers.

Sometimes translators can do both at once. But which way should a translator go if those two paths don’t align? This is why many of the classics have multiple translations by several authors who made different choices.

But Polish linguist Robert Stiller was not confused but instead challenged when he came upon Anthony Burgess’ “A Clockwork Orange,” a book turned into one of the most influential movies in history by British director Stanley Kubrick. Having to choose among a few translation options, he went two ways, one after the other, and announced a third, which, unfortunately, he never completed.

Robert Stiller, From Odin to Jabberwocky

Born in 1928 to a Polish-Catholic-Jewish family, Stiller was one of the most notable linguists in Polish. Having graduated in Polish, Slavic studies, Indology, and even Nordic studies from Reykjavik University in Iceland, he traveled across the world, including Southeast Asia, and was interested in esoteric philosophy while immersing in world languages’ richness and learning over thirty of them.

A poet, progressive anticommunist, social publicist, and even, at some point, politician, he is perhaps most famous as a translator from English – the first to introduce the James Bond series, the perfect choice as a translator of sophisticated and melodic Nabokov prose, experimental Lewis Carroll’s Alice books and nonsense-fueled Jabberwocky, a heroic epic from ancient India as well as Nordic cultures, some Malayan literature 101 – you get the point, or rather the scope. And then, there was “A Clockwork Orange.”

Was “A Clockwork Orange” dystopian?

Written in 1962 by English author Anthony Burgess, the book concerns moral panic over the rise of subcultures and the violence embedded in the social politics of the modern world. But being dystopian…

A side note here: in the introduction to his translation of another of Burgess’ books, “1985,” Robert Stiller digs deeper into the word “dystopia.” As he points out, the word “utopia,” contrary to popular belief, doesn’t mean “a good place,” as the Latin prefix U– is not the same as EU-. EU– means good – as in euphoria, which means a feeling of intense happiness or excitement. U– is just “the opposite”; (u)topia is a place that doesn’t exist.

Anyway, if you consider utopia as eutopia, still the opposite word – as Stiller says – is created wrong. It should be cacotopia, not dystopia, in the same way that cacophony is the opposite of euphony. This is to show you the depth of the intervention in texts and the reflection on it by Robert Stiller’s translational oeuvre.

So, “A Clockwork Orange” would be an “ecotopian” novel; in the world that it creates, the language is different, representing English under heavy influence by Russian, perhaps as a suggestion of their cultural dominance. Alex’s saying “horror show” was both an accurate description of his taste, but also an allusion to khorosho, “good” or “well” in Russian. Alex’s gang refers to themselves as Maliki, Russian for boys, etc.

The English, the Russian, the German

So, where should a Polish translator go from here? Yes, in the 1960s, the Russian influence over the Polish language was a threat, with some remnants of it to this day. In modern Polish, bumaga, Russian for paper, is still a derogative term for overzealous paperwork, and the Russian alphabet is referred to as bulk, the Russian for the letter.

But what about English, coming in waves, especially after the fall of communism? And German? The language of both Austria and Germany, two of the 19th-century countries ruling the Polish territory, and later, of the German Nazi empire forcing out Polish culture in occupied Poland?

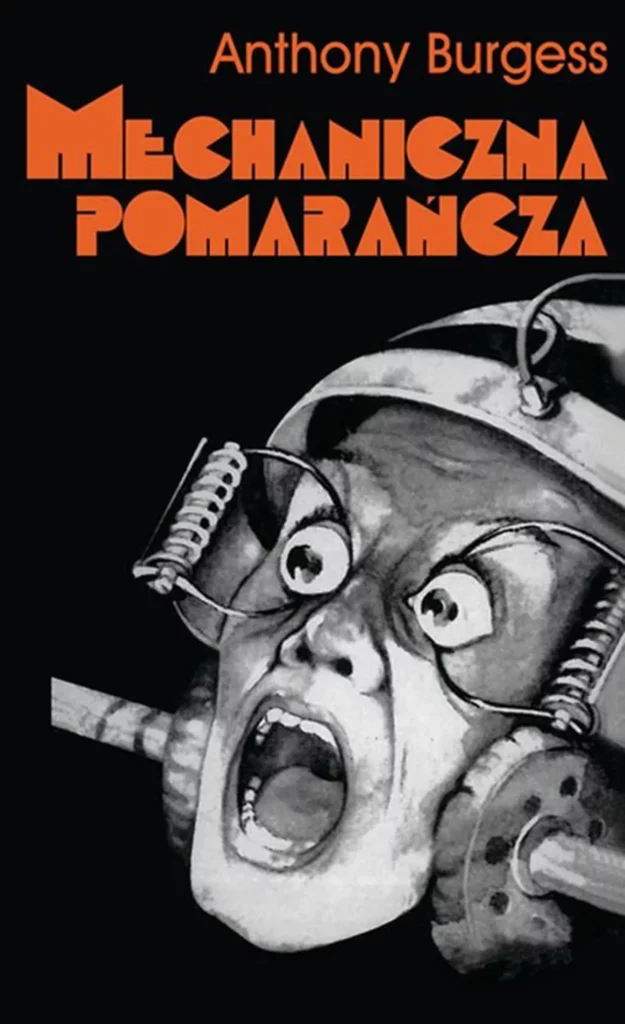

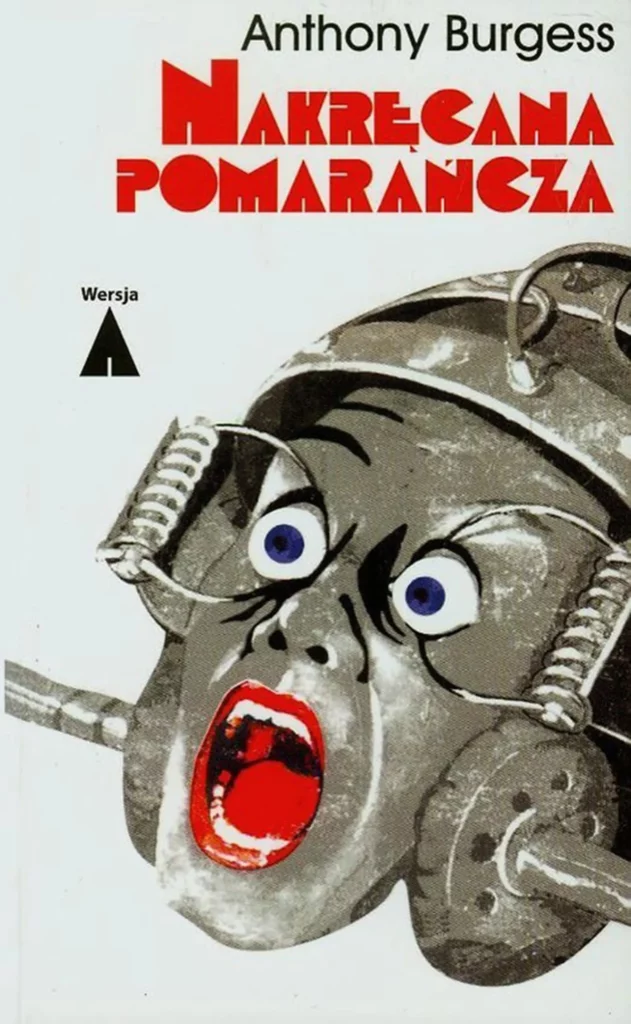

In the early 1990s, the two translations of “A Clockwork Orange” hit the market from the same publishing house. They have almost the same cover – Alex DeLarge, his eyes forced open under the Ludovico Treatment, screaming in his own horror show. But the cover of one book is black; the other one is white. The white one is marked “Version A,” A being Angielski – English, as opposed to the R version of Russian-influenced Polish. Also, the titles were different – the R version being “Mechaniczna pomarańcza,” and the white – “Nakręcana pomarańcza,” both rightful equivalents of the word “clockwork” (Mechanic vs. Wind-Up).

As the publication was possible only in the 1990s, the simultaneous publication of both editions results from years of previous works and the inability to publish them. But a third work was still under construction – the N version, N for “Niemiecki,” the Polish word for “German.” Robert Stiller repeatedly underlined that the version was underway, but when he died in 2016, it was neither completed nor revealed. Stiller even dubbed “Sprężynowa pomarańcza” (“A Spring-Assisted Orange”) as “The Annoying Orange,” indicating his constant trouble finishing the trilogy.

But was it really a trilogy? Hard to find another word for the intended completed work, as there is little to compare the project to. Robert Stiller was always ready to take up the challenge whenever the challenge was language. The sound, the riddles, and the difficulties are what drove him in his work. But when he did what he did best, it was always a horror show.