Years of increasing tensions on NATO’s eastern flank and months of military buildup leading to the Russian invasion of Ukraine have made the issue of borders in Central Europe one of the most important geopolitical factors in today’s world.

The rising “fog of war,” contradictory narratives, and propaganda gimmicks have led to misinformation regarding the complicated history of Central and Eastern European Countries. To untangle some of these narratives, it’s important to look at the eastern border of Poland, the longest single line of NATO’s eastern border.

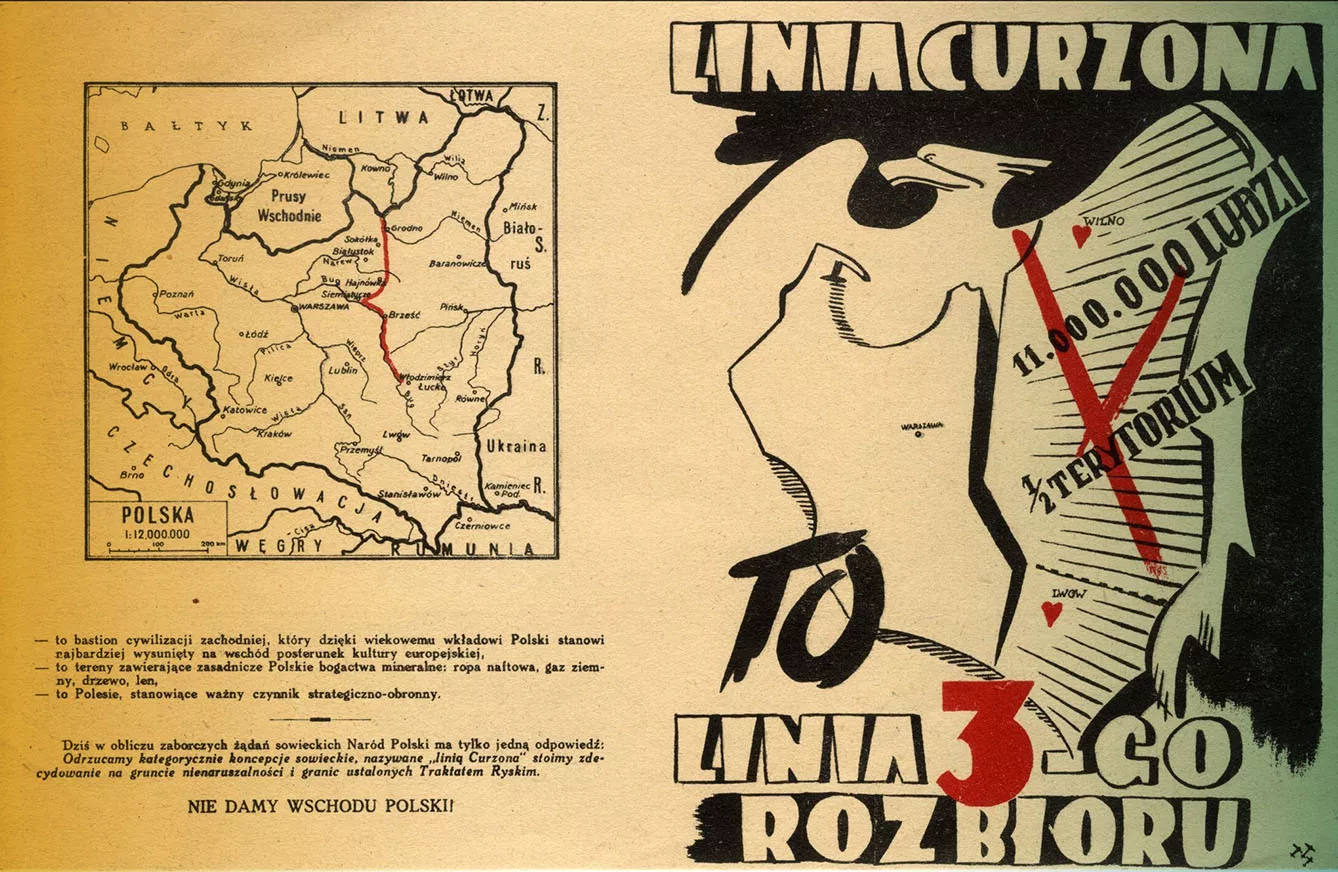

The confusing Curzon Line

Poland’s Eastern border meets three countries: Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine. But the line drawn there predates all of the current countries in the region. Now known as the Curzon Line (named after a British foreign minister a hundred years ago), it is rooted in the 18th-century history of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and, though unrecognized, also Ukraine.

The bonds between Poland and Lithuania that have existed since the 14th-century grew stronger over the centuries. In the late 14th century, Lithuania, the last pagan country in Europe, Christianized, and its High Prince Jogaila became Władysław Jagiełło – King of Poland.

The union of these two independent countries turned into one large empire in the late 16th century. Rooted in Western culture by Catholic Poland, it incorporated much of the Eastern culture, as well as territories of current Ukraine, which had been colonized by Vikings from the north centuries earlier.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was in decline in the late 18th century, and it was partitioned between the 1770s and 1890s. The first Constitution in Europe, passed on 3 May 1791, was a futile effort to undo the damage, and soon, during the third act of partition of Polish territory, three modern empires – Russian, Prussian, and Austrian, virtually annihilated Polish political entity for all of the 19th century.

Recycling borders

When it reemerged in modern times, in the aftermath of World War I, the demarcation line of this 1795 partitioning served for Western countries to establish a new Polish political entity. But it was no longer a time of empires; this was a time of nation-states. So, research was made, allowing a determination of people’s national identities on the frontier.

The next few years were unstable, and several political forces emerged in efforts to establish independent countries in the East. Based on that, a line was roughly drawn between the Polish and Ukrainian/Ruthenian majorities. Hoping to export the Communist Revolution to the Western European heartland, Vladimir Lenin, leading the Soviet country, invaded two-year-old Poland, but in August 1920 was pushed back from Warsaw, which assured Poland’s existence for years to come.

Then the demarcation line issue reappeared. As discussed at Paris Peace Conference, national research came in handy with the March 1921 Polish-Soviet Peace Treaty of Riga, and the resulting border was far more generous to Poland in the east. But the line as an idea was already there.

The Curzon Line, reborn

And mostly, it came to life three decades later. Under negotiations between Western allies and Stalin in Tehran and Yalta, a new Polish border was proposed. One exception from its original design is L’viv, excluded by secret adjustment by Curzon’s advisor. The city itself had a Polish majority and was considered vital to Polish culture.

The resulting, only slightly adjusted border was set in 1947 and has remained Poland’s eastern border ever since. Centuries of circulating the idea are proof of how complicated the issue of eastern borders is. And confirms that, unfortunately, there’s a lot to play on for spin doctors.