Danuta Nierada: Could you tell me your first memories of Tamara?

Marisa de Lempicka: I met her when I was a little girl. I was lucky enough to spend summers with her in her house in Cuernavaca, Mexico. I grew up in Argentina. It was a very, very long trip to visit her there. [The first time], I was about four years old. We traveled with my mother and sister all the way from Buenos Aires to Cuernavaca, Mexico. It took about twenty-six hours by plane and car, and we finally got to Tamara’s home – the house called “Tres Bambus”.

To get to the villa, we had to walk through small cobblestone streets, and we saw a big wall with a small red door, and Isidoro, the chauffeur, who was also in charge of the house, came and opened the door. Then we walked all the way through the most beautiful garden I had ever seen. We were housed at a small casita behind the pool. So, we changed. We put on our nicest dresses and finally got to meet the great Tamara.

I knew her already. I grew up looking at books; I remember the colors of her paintings, and I’ve heard the story of her style, her fashion. I knew I was going to meet someone great. I first saw her walking down the stairs. She loved to wear long tunics that she designed for herself. She had tunics in every color, with all kinds of patterns, and, of course, a big matching hat. She would smoke cigarettes from a long cigarette holder, always a cigarette in her hand. She had the most amazing jewelry, the biggest gold and diamond jewelry I had ever seen. I had never seen anyone dressed like that.

Red lips, smoky eyes – the most beautiful, big, blue-turquoise eyes, and she had a very hoarse voice from smoking all her life. She says, “Hello, Marisa, you can call me Cherie.” No grandmama or granny – she didn’t want people to know how old she was. She was always Cherie to us, and we were always introduced as “the girls.” She hugged me the tightest, and I remember the smell of her French perfume, and it was just like that. I [had] never met anyone like her.

Tamara de Lempicka: the epitome of style

She was a grand dame until the day she died. You would never see Tamara without her hair and makeup done or in a bathrobe or pajamas. She wouldn’t leave her room without eye makeup, lipstick, perfume, and her hair done. I think it was very important for Tamara how she presented herself to the world. Even when she was in her seventies, her appearance was very important to her. She didn’t want to limit anything.

Tamara was one of the best painters of her time. But there were thousands of hungry artists in Paris at the time, and every one of them wanted to succeed and become famous. How did she manage to climb to the top?

She was one of the greatest painters of her time. Even now, she is considered one of the best painters of the century. We can name so many male painters, but we can name very few female painters. Tamara is the third most expensive female painter in history. A few years ago, a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe sold for USD 44 million USD. The second most expensive female painter is Frida Kahlo, whose painting sold last year for 30 million USD. Tamara is in third place. She broke her own record with “Portrait of Marjorie Ferry”, 1932, which sold for almost USD 22 million in 2019.

So, it still surprises me when people don’t know who Tamara is. Today you may not know her by name, but you may recognize her paintings. She created an iconic style, something that had never been done before. And she was able to combine very different styles and techniques.

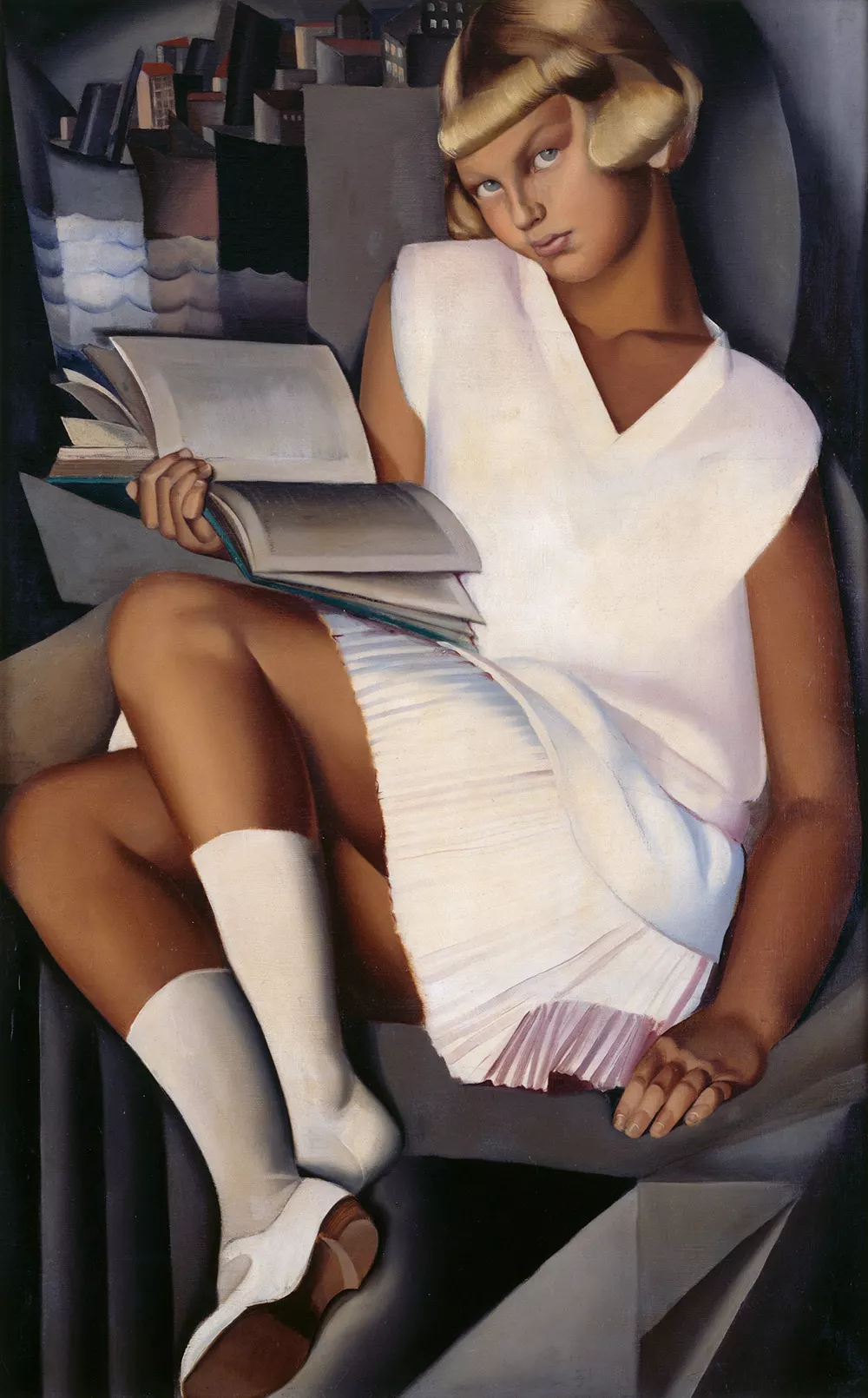

She fell in love with Renaissance art on her first trip to Italy with her grandmother Clementina. They traveled from Warsaw to Florence, Rome, and Venice, where they visited the Uffizi Gallery, the Accademia, and the Sistine Chapel. She was amazed by the way the human body was portrayed in these paintings, with all their perfection and beauty.

The Tamara Blue

Then, in Paris in the 1920s, where Cubism was the king of style, she mixed soft Cubism with Renaissance techniques and point of view using the most beautiful colors. She called her blue the “Tamara blue,” which she made from lapis lazuli. Her greens were made from malachite and her vermillion reds from cinnabar, creating unique bright colors. By mixing these styles and putting her own soul into her paintings, she created something special.

Nowadays, the prices of her paintings are very high at auction. But how was it when she was a young artist in Paris?

Tamara had to flee the Bolshevik Revolution from Saint Petersburg, where she lived with her new husband: Tadeusz Łempicki, who was a Polish aristocrat and lawyer for the courts. Her family had an estate with many servants. They had a fabulous life there – they went to all the parties, the theatre, had designer clothes and jewelry, vacationed in the top destinations in Poland and in Europe. Then, overnight, they lost everything.

Tamara would tell the story about how they were [newlyweds] making love in the middle of the night when the Cheka police burst into the room and took Tadeusz away to prison. Thanks to her connections and determination, she was able to save him from a Bolshevik jail.

She fled to Paris, and a few months later, Tadeusz was able to join her. He returned a [broken] man. How could he not? His soul was destroyed. God knows what happened in that Russian prison. We can only imagine.

They ended up in Paris with nothing. They had already had my grandmother, Kizette, who was just a small child. They had to survive. After selling [her] last bracelet, Tamara had to do something.

She had a talent for painting. So, her sister Adrianna Górska, who was one of the first women in Europe to earn an architecture degree, suggested she become a painter. “Why don’t you paint?” she said. “Why not? You have always been such a good artist.”

Tamara thought it was a great idea. She already had contacts in [Paris society] – a lot of Polish aristocrats and immigrants from the upper classes lived in Paris. So, she decided to paint portraits. But she also decided to succeed. She promised herself that [she would become] the most sought-after portrait painter of her time and would demand the highest prices for her paintings. She was not going to be a starving artist.

She told me a story when [I was a little girl]. She promised herself that she would buy one diamond bracelet for every painting she sold and that she would not stop until she had bracelets from her wrist to elbow.

Diamond bracelets have several uses and messages. The first is to show success. Second, of course, they are beautiful. But also, understanding the history of refugees, they gave her security. She always carried this fear with her. She knew that if she ever had to flee again, she could take those diamond bracelets with her and start again somewhere else.

Tamara was great at doing her own publicity. She produced several stories about herself that changed over time. She claimed that she learned to paint as an adult in Paris, to support her family. Do you think it is true?

Tamara de Lempicka was very secretive. {Having been] a refugee, she was extremely afraid of the Bolsheviks, then the Communists, and then eventually the Nazis. And then, we found out about her Jewish background. There were many secrets in her life. We don’t know the exact date of her birth. We don’t know exactly where she was born, though, of course, she always claimed that she was Polish. But all those documents were lost, so she kept an aura of mystery about her past.

She was a woman who wanted to portray herself as a self-made woman. A woman for whom everything she did and everything she accomplished came from within… [from] her own strength. But … we suspect she probably studied art in Saint Petersburg, and then, of course, she continued her studies in Paris. But this is our suspicion just because the perfection of her art is amazing. To get to this level of mastery, you need to study, study, study, and then work hard and practice.

She enjoyed life and attended eccentric parties and the nightlife of Parisian bohemians. But she also painted a lot. How did she manage to combine hard work with being a high-life society woman?

She was probably bipolar. We say this because she had her highest highs when she would work all day go to parties at night, paint until dawn, sleep a few hours and then go to more parties. It lasted for several years, and then she would go into a deep depression or just [exhaustion]. She would sleep for days. I think it’s similar to a lot of artists. That’s how they get this extreme passion.

Tamara was a great artist, but she also knew how to sell her art.

She promised herself she was not going to be a starving artist. She understood self-promotion very well, and I think this is one of the reasons why her art is well known. Because she was a commercial artist. Later in life, she didn’t need to sell her paintings, but she continued painting until the day she died. She explored many different subjects and styles, but in the 1920s and 30s, she had to sell her paintings to survive and to get back what she lost: the jewels, the property. And she did.

She had the most fabulous apartment in Paris. She painted there because it had floor-to-ceiling windows, and she loved to use natural light. But she also used this place as her own gallery. It was the perfect backdrop for her paintings, with sleek art deco furniture and pearl grey walls. She was her own agent and negotiated the highest prices for herself. You can imagine creating this amazing art but also being a smart businesswoman, with quite unique skills to combine, using both sides of the brain.

And then, she used the media. She invited top art and society journalists to come to her openings because, you know, the media helped her. She threw the most amazing cocktail parties and receptions; some could be scandalous. She was totally like an Instagram star in her days. She would have the top designers give her dresses to wear on those occasions.

She would wear these amazing clothes while presenting these beautiful paintings. And then she would have some of the best photographers of the time taking her portraits. When people from the newspaper would come to her parties or ask her for an interview, she would give them these wonderful pictures of her – not just any pictures.

She realized that this gave her star power. People wanted to be close to her and know more about her, which helped her sell more paintings, which was her goal. She was incredibly innovative in thinking this way because no one was doing that in those days.

Tamara de Lempicka and Art Deco

At that time, the Art Deco style came into fashion, and everyone was decorating, furnishing, and redecorating their homes. The only thing missing were paintings in this style on the wall. And this is where Tamara comes into the spotlight.

She is “the” art deco painter. There really is no one else. She took the spirit of the day. She understood fashions but was able to create her unique style of painting based on different styles. Paintings that matched these modern times. Everyone wanted to have a Tamara de Łempicka painting on their wall.

We see a lot of women in her portraits. How did she understand the role of women in society?

We see a lot of modern, fabulous women in her paintings. You can see their attitudes. They are responsible for their lives. They are defiant. They are confident. No demure muses – just strong, demanding women in charge of their lives and their futures.

Women started doing the same thing as men. This was the generation after the 1920s when women could have their own bank accounts. They could have their own real estate. They could cut their hair. They could breathe because they didn’t have to wear those stupid corsets. Everything changed for women in the 1920’s

After World War I, many men were wounded in the war, so women fixed buses and lights on the streets. This gave them new power that they never had before. When the men returned, the women wouldn’t give back this newfound freedom. So yes, they were partying. They explored. They were a bit scandalous. They tried new things.

Tamara lived in several different countries – from Poland, Russia, and France to the United States and Mexico. But she always claimed that she was Polish. How did it show?

She claimed that she was a citizen of the world because she lived in so many places and really adapted to each place she lived in, but she always said that she was born in Poland. She came from a Polish family.

Her grandmother Clementina, who is [buried] here in Warsaw at the Jewish cemetery, was instrumental in Tamara’s upbringing. She was the one who took her to Chopin concerts and the most amazing museums in Europe. She also gave her the confidence that she could do and be whatever she wanted. She spoiled her a bit. But she was strong and powerful. In those days, she was the head of her household with twenty servants, several houses, etc.…

In my time, we had Polish food at Christmas. She would serve bigos, pierogi, borscht, and mizeria (fresh cucumbers with sour cream). Tamara and her daughter, Kizette, my grandmother, spoke Polish, especially when they didn’t want us to understand what they were saying. Tamara decorated her homes in the States and Mexico with this kind of grand old Polish decor.

She stopped painting or exhibiting for years, and then after two decades, she returned to the world. How did that happen?

Tamara never stopped painting. She painted until the day she died. She was an artist by nature, and she had to create for the rest of her life. Some things were better, some not so much, but she was always creating. When she moved to the United States, she didn’t have to sell her paintings.

Her second husband, the Baron Raoul Kuffner, owned a huge fortune in the meat and brewing industries in the Austro-Hungarian empire. At the time of the rise of Nazi Germany, she convinced him to sell all his possessions in Europe and go to the United States. He had one of the largest art collections in all of Europe, and unfortunately, they had to sell it quickly, so they got less money than it was worth.

She knew the terror that was coming because she had gone through the Bolshevik Revolution. She traveled to Berlin because she was doing the covers of German “Die Dame” magazine, and she saw young people with this extreme hatred and almost too much passion, like passion for the extreme. Almost no one could have thought that Germans would come to invade Paris. She saw it before anyone else… And because her father was Jewish, and her mother as well [but had] converted to Calvinism, and her husband, Kuffner, came from a Jewish family, she knew they had to flee. She saved his life and money.

In the 50s and 60s, art deco and portrait painting went out of fashion. It was Abstract Expressionism time. She couldn’t identify with it. [She believed that art] had to be beautiful. It had to show the beauty of the human soul, the beauty of the human body. It had to be of excellent technique. None of that was trendy anymore. But then, in the late 70s, Art Deco became fashionable again.

There was a gentleman from Paris [named] Alain Blondel. He was an art student. He discovered Tamara’s work through the archives in the library. He was writing about art and [found] these newspaper articles from exhibitions in the 1920s. He came across an article about Tamara’s first opening in Milan, organized by Prince Emmanuel Castelbarco in 1925, with some photos from that exhibition. He had never heard of her.

In those days, there was no internet. He had just newspaper articles. He went through the phone book and looked for her. Tamara kept her apartment in Paris until the mid-’70s. He called her, and she answered the phone. He said: “I’m interested in your art.”

He went to visit her, and she thought he would be interested in the palette knife [paintings] she was making in those days, but he said, “No, I’m interested in [your] paintings from the twenties and thirties.”

She said, “These are old things. No one wants to look at them anymore. They’re here in the attic”. She had them all gathered in the attic, those fabulous artworks worth millions of dollars today. She gave him the key to the attic, and he went there.

He says it was like finding a treasure. He persuaded her to allow him to launch his newly founded Galerie du Luxembourg with her retrospective exhibition. And it was a huge success.

She was very smart, she sold a lot of her paintings, but she kept many of her expensive paintings and then donated them to French museums. That’s what we see in today’s exhibitions. She wanted to leave a legacy, and she knew that if [her paintings] were in museums, [they] would probably never be forgotten.

How many paintings did Tamara create?

There is a Catalog Raisonee done recently by Alain Blondel where you can find five hundred and twenty oil paintings and drawings, but we know there’s more because some in our family archives are not in the catalog. So, I would say about five hundred and sixty paintings that we know of.

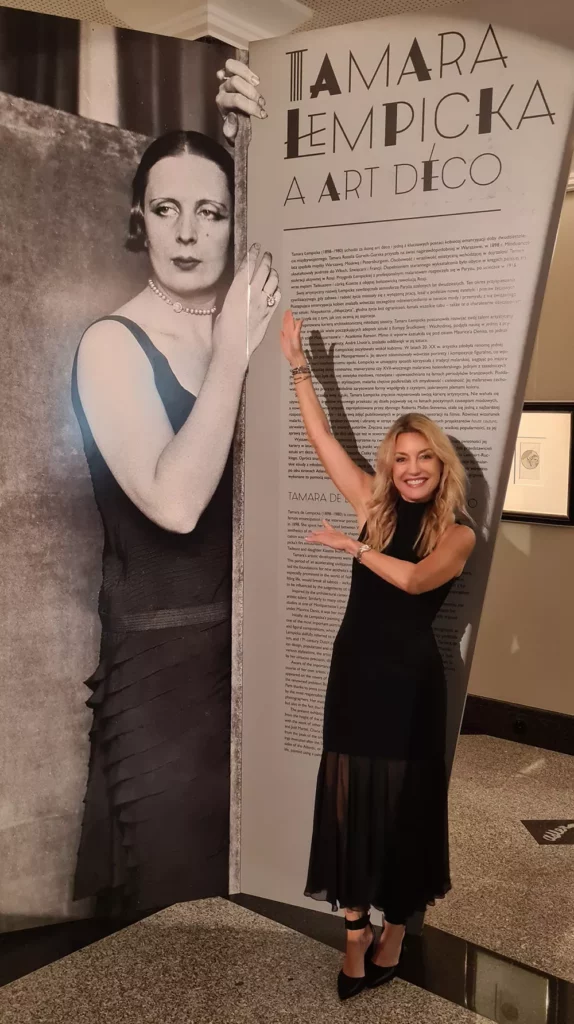

A Tamara de Łempicka exhibition in Krakow just opened last week. What’s your impression?

It is an amazing success. There was a two-hour waiting line on the day of the opening to see the exhibition and at least a one-hour line every day after that. They had almost four thousand visitors in four days, so they have never seen anything like this! They have about thirty works presented in an excellent, very modern, and unique way, as well as many of Tamara’s portraits taken by famous photographers of the day and 3 mini films featuring Tamara at different points in her life.

It is also important to mention that another exhibition just opened at Villa la Fleur, in Konstancin, outside of Warsaw. This is a very different exhibition, but truly worth visiting. Villa la Fleur is the perfect setting for Tamara’s paintings. This exhibition features several of her famous works but also many early and later works that have never been exhibited. It might give the visitor a whole new perspective on Tamara’s work.

Thank you, Marisa. That was a pleasure.

Thank you.

*The Tamara de Łempicka Exhibition is currently featured at the National Museum in Krakow

From September 9, 2022 – March 12, 2023