All four corners of Warsaw’s busiest road junction each reflect slightly different epochs of the city’s life. On one corner sits the Palace of Culture and Science – a socialist-realist skyscraper “offered as a sign of goodwill” by the Soviet Union in the 1950s, soon after Poland had been recaptured from Nazi occupation.

In another corner, you can find a 1970s elegant, modernist urban space with prominent department stores – Domy Towarowe Centrum, the staple destination for shopping for goods under socialism.

The third corner is occupied by yet another prominent building – a Hotel, traditionally known as the Forum (now operating under the Novotel brand). The building is a symbol of allowing the Western culture, tourism, and money in the People’s Republic of Poland. Only one of the four corners – although still dressed in modernist clothes – remembers Interwar Warsaw with its quarter of 19th-century houses, unique for this city.

Warsaw war destruction

The obvious reason behind the modern appearance of Warsaw’s central hotspot is the Second World War. The German invasion of September 1939 damaged the city, but it was the subsequent liquidation of the Jewish Ghetto (and the Ghetto Uprising) in 1943 that contributed to the methodical wipe-out of the major part of the city. That was followed by the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, which provoked a planned demolition of what was left of the city.

Anything that remained took heavy shelling during the Soviet siege of 1945. According to some estimations, approximately 95% of Poland’s capital was destroyed, with many districts turned completely into a pile of rubble. What remained of this once beautiful city was so useless that the act of rebuilding Warsaw was considered to be ideologically motivated, as there was no logic to support such a desperate decision. Therefore, areas such as the Old Town are not just a monument to history, but a testimony to the rebuilding effort (and as such included on the UNESCO Heritage List).

Hotel Polonia: the fourth corner

As unreasonable as it may sound, life started to return to the nearly-annihilated city, and business as usual eventually followed. After all, reconstructed or not, in early 1945 liberated Warsaw was still the rightful capital of Poland and the destination for politics and diplomats. Though, when you think about diplomacy, the last picture that comes to mind are ambassadors nesting among grey ruins of roofless buildings.

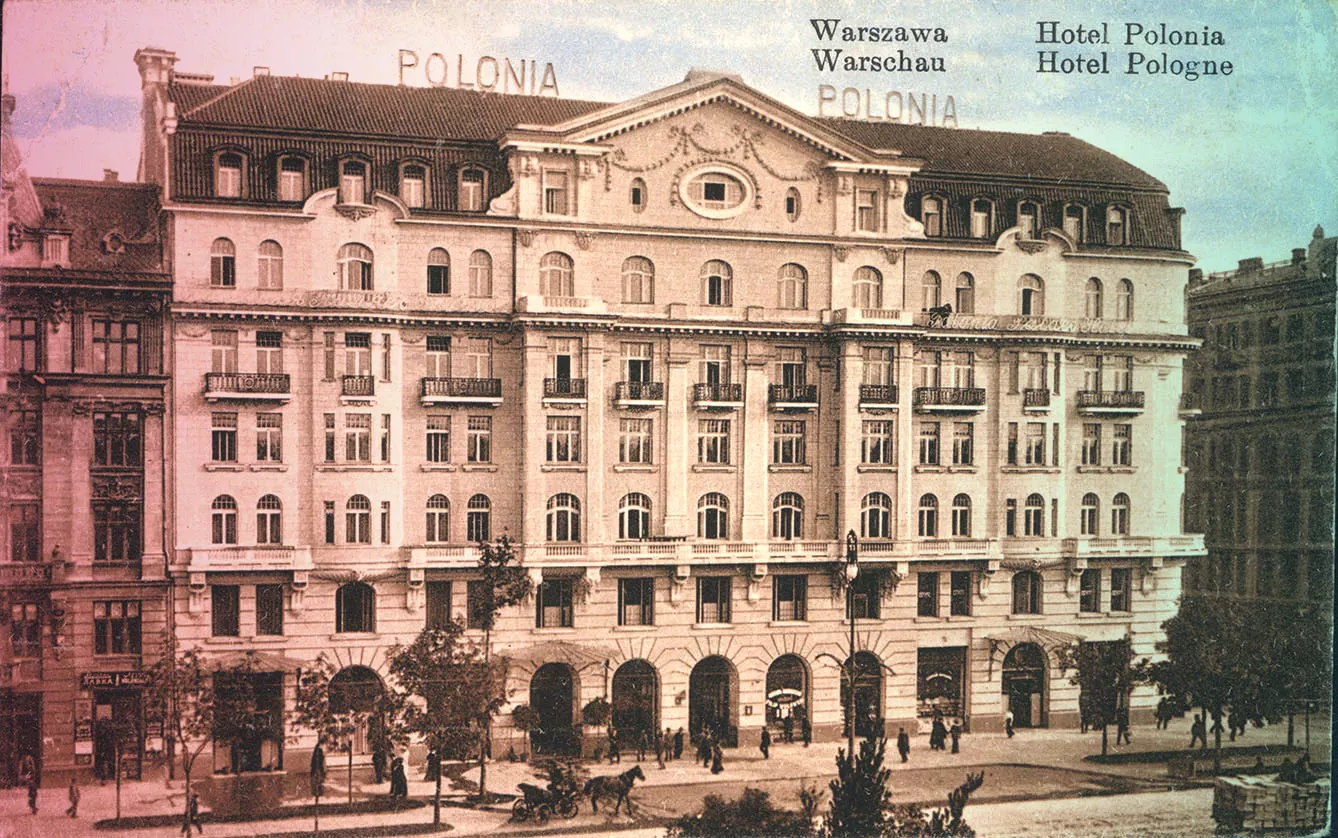

So where could Poland house all the allies’ emissaries, who were desperately needed to coordinate the rebuilding effort? As it turned out, there was only one location that offered appropriate conditions. On the corners of Marszałkowska and Aleje Jerozolimskie Streets, there was a hotel that not only had a roof but also was connected to the power grid and water supply – a thing so scarce at the time that it could be considered a miracle. The building was – and still is – the Polonia Hotel.

The German engineers that were in charge of the city’s methodic demolition were stationed in this luxurious venue, so it was possibly the last one scheduled for demolition – just as in the well-known revolutionary French satiric picture where Robespierre puts the last French – the executioner – under the guillotine. Germans didn’t complete their plan, forced out of the city before destroying this last surviving structure.

Diplomatic Polonia Hotel – not all destroyed

Therefore, out of two hundred luxuriously designed rooms, nineteen became the makeshift embassies of different countries. They served that purpose for the time when the diplomats were overseeing the reconstruction of their designated embassies.

It’s easy to imagine the atmosphere of the “diplomatic hotel.” With the Western Allies and the Soviets growing apart, the planned regime change from Pro-Western to Soviet-subjected Poland, and Warsaw as one of the important capitals of Central Europe, the embassy hive was home to dozens of politicians and spies.

So how can you effectively spy on your hotel neighbor? How can you call the Foreign Affairs Ministry in your country if the operator connecting your call is the same one who works for the other eighteen countries? How can you respect the exterritoriality of your embassy, if it’s behind one of the dozens of same-looking doors located in one corridor, where, apart from the ambassadors, there are also “tourists” staying in the same venue?

Polonia, now independently operated under the name of Polonia Palace, is still an important hotel on Warsaw’s hospitality map. It does not house any embassies anymore (but, no doubt, a spy is staying there every once in a while). Nevertheless, the diplomatic episode in the venue’s history is commemorated by an inscription on a glass plate attached to the building’s wall. A diplomatic way in which to remind the troubled contemporary history of the country.