In the 16th century, the Slovenian Lands went through a major crisis with the Reformation. The spread of the new creed began weakening the Catholic Church and causing many upheavals, both socially and politically. As Slovenia was then part of the Holy Roman Empire, Martin Luther’s ideas quickly gained momentum, with sympathizers cropping up in Slovenian lands.

The birth of written Slovenian

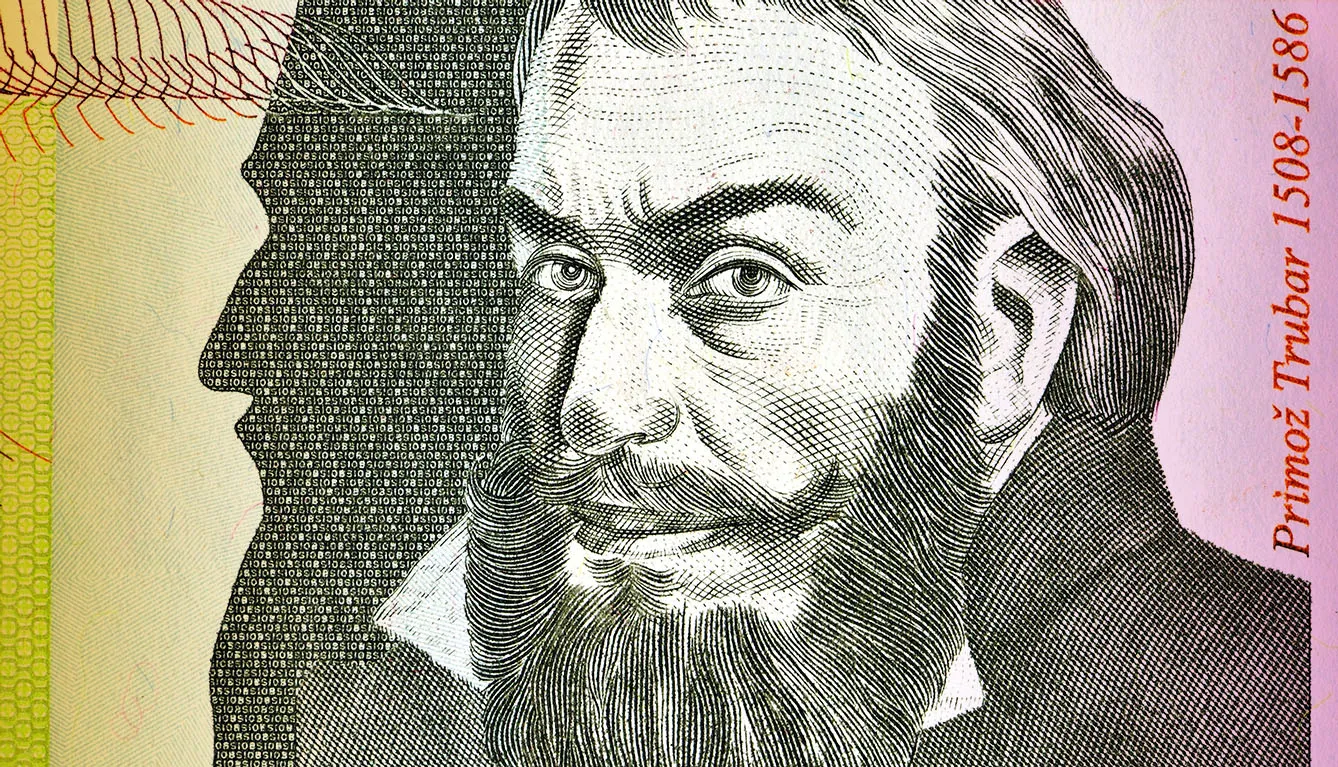

It all started with Primož Trubar. He was a gifted priest who was able to study thanks to the patronage he received due to his obvious intellect. He came in touch with Protestant ideas and was sympathetic to them. He eventually fully embraced the new faith and started fervently spreading it. But for that, he needed to bring the Bible and Protestant literature closer to the commoners.

Unlike other languages, Slovenian, at the time, was strictly a spoken language, prevalent among the peasant population across certain duchies and counties. In order to convert his people, he started a process of creating a written language for them. After facing many grammatical challenges, in 1550, he published the very first Slovenian language book, “Catechismus,” a collection of Protestant teachings, followed by “Abecedarium,” a booklet for helping people learn the alphabet.

In the former, he was the first to call Slovenians by the name they have today. With his followers, he went on to produce dozens of works, which was unusual for a small, peripheral linguistic community. Slovenians got their first printed book before many much bigger nations.

One of the first vernacular Bible translations

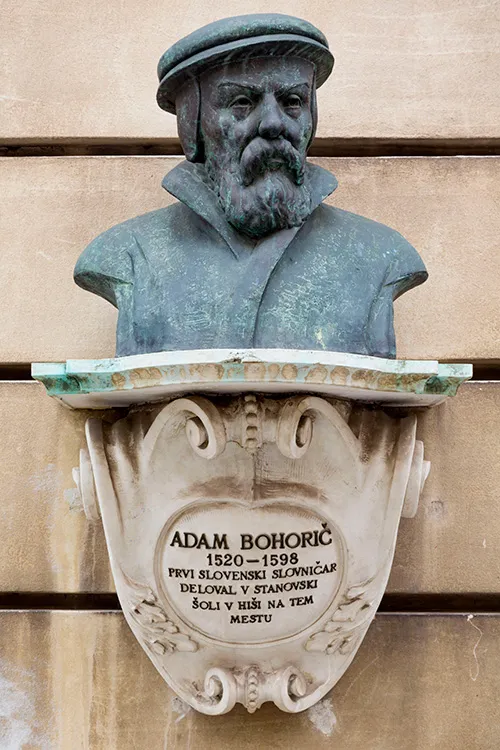

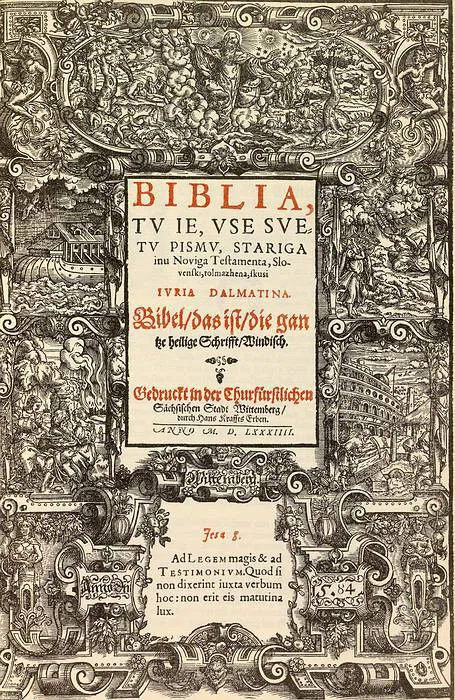

Jurij Dalmatian, who came a generation after Trubar, translated the entire Bible into Slovenian, published in 1584, making Slovenian the 12th language out of the current 3,589 into which it was translated. Other Protestants were also responsible for this cultural revolution, including Adam Bohorič, who wrote the first book on stylistic Slovenian grammar.

Eventually, the Slovenian lands were retaken by Catholicism, and Protestants had to convert back or leave by the 17th century. Trubar eventually died in exile, as did Bohorič. But they forever left a mark. Slovenians, although small in number, from that point on, continued to develop into a modern nation, basing the core of its identity on the language.

Most of the books they wrote were burned during the counter-Reformation, but the Catholic Church conserved Dalmatin’s Bible and permitted its usage. Eventually, the Church played its own role in nation-building, ironically utilizing the works of the Reformers in this pursuit.

They are well remembered today with many monuments, not to mention the fact that Trubar is currently depicted on the euro coin – and before that, on a Slovenian tolar banknote. Protestants represent less than 1% of the Slovene population today, but the Day of the Reformation is celebrated as a national holiday, celebrating the language that gave identity to the nation. No other Catholic nation owes so much to Protestants.