It all starts with two brothers and a conspiracy. Their conspiracy was a socialist movement against Russia’s tzarist rule over Poland, which in the 1880s had lasted already for a century. The co-conspirators bear the family name Piłsudski. One of them, Józef, later became perhaps the most notable political figure of the century in Polish politics. And the other brother… well.

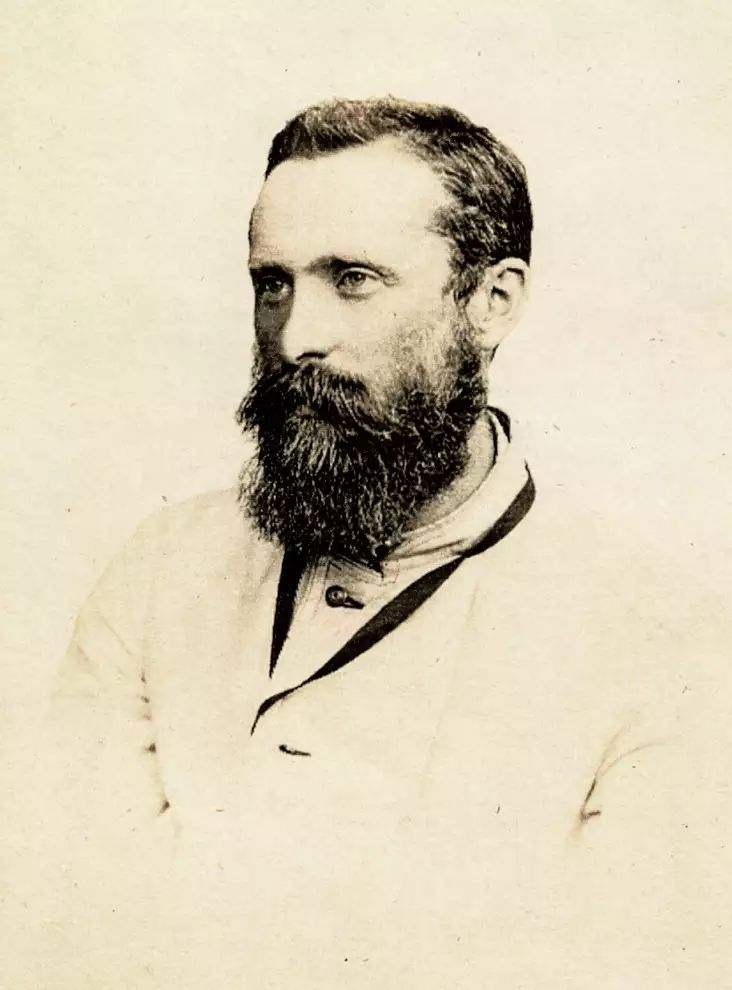

Bronisław Piłsudski: revolutionary etnographer

Bronisław Piłsudski’s career as a revolutionary didn’t go so well. In the late 1880s, he was incarcerated, Russian-style, and sentenced to hard labor and exile on the remote Siberian Sakhalin Island. That resulted in two important encounters and a major shift in Bronisław Piłsudski’s career.

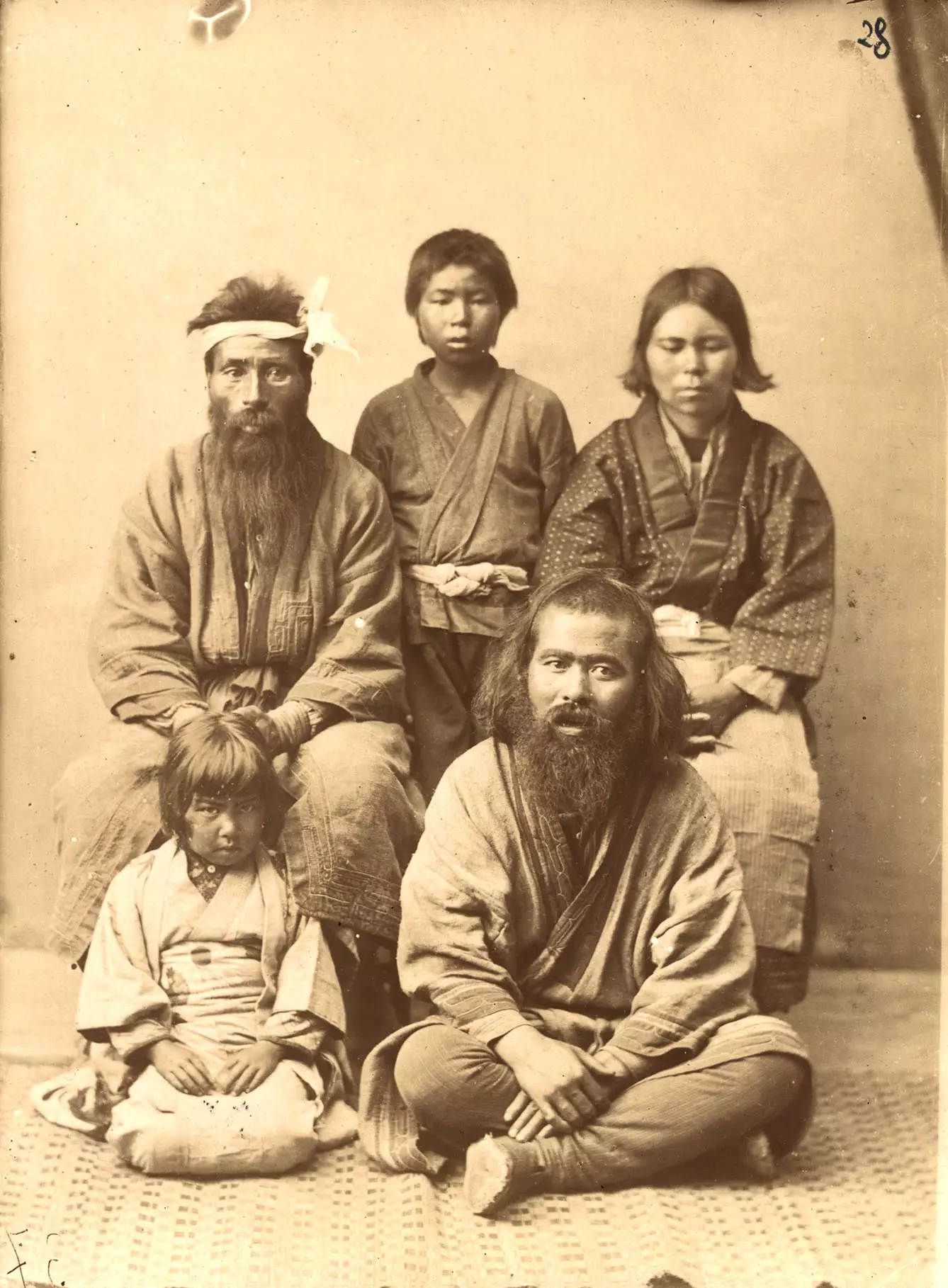

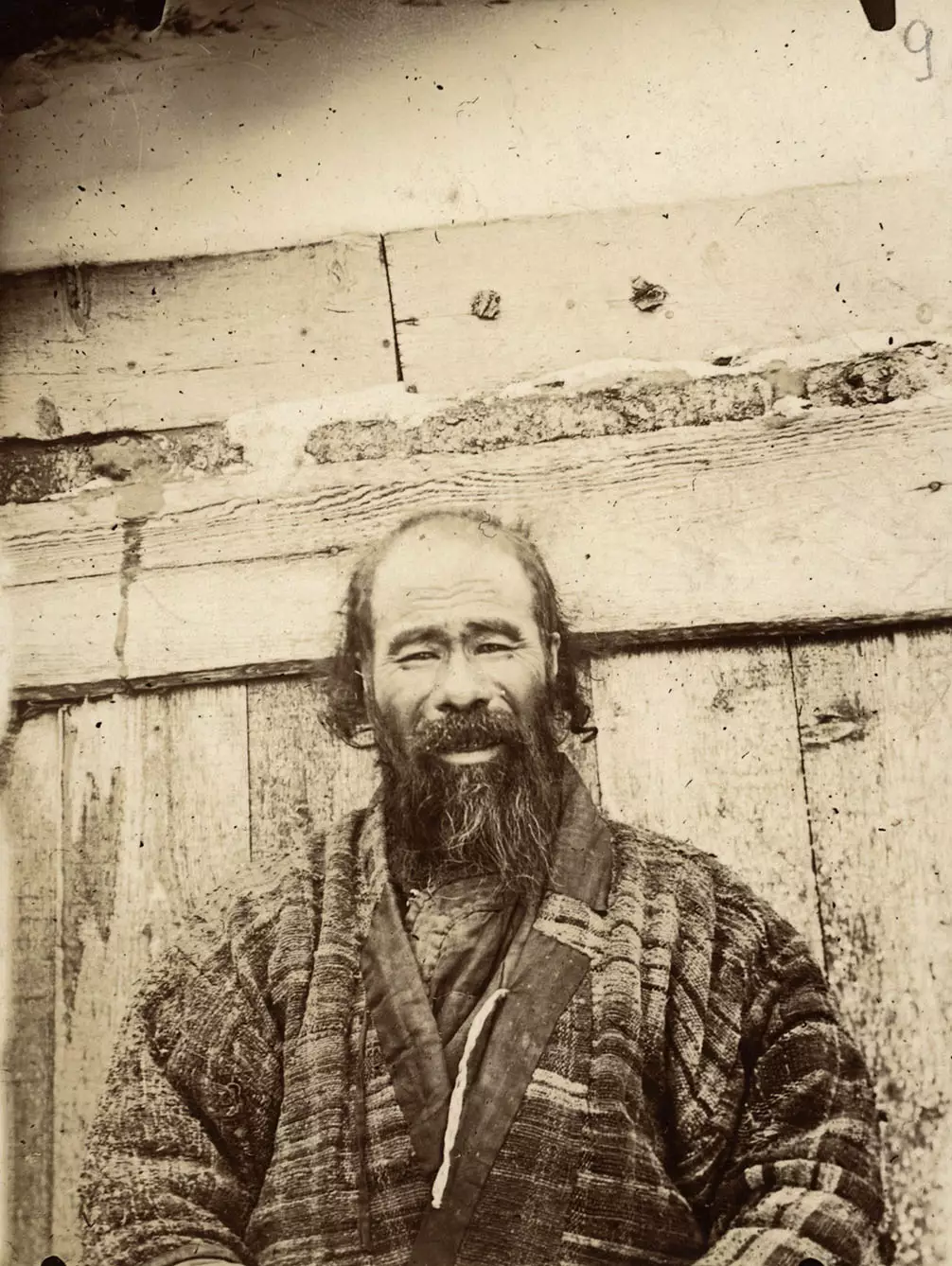

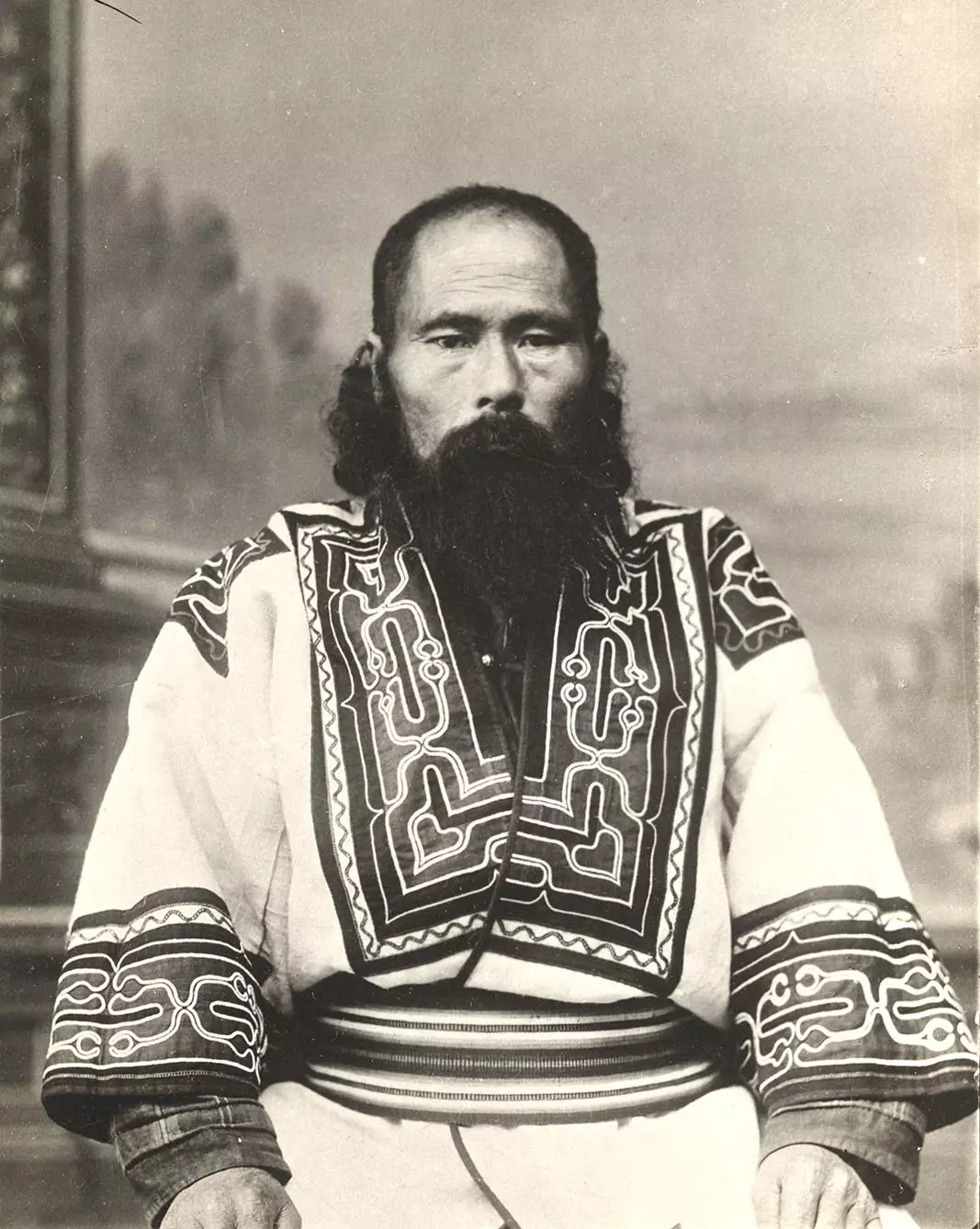

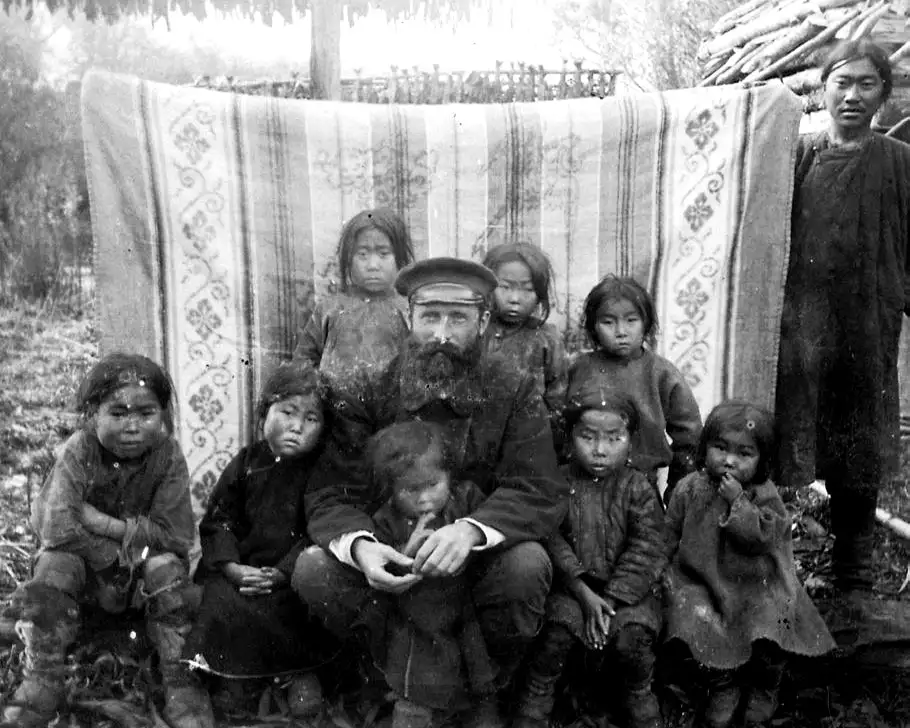

One of such encounters was with Lev Sternberg, a Russian ethnographer who was working on a commission for the American Museum of Natural History to document the indigenous peoples of Sakhalin. The other encounter was with the native population, particularly the Sakhalin Ainu. And then there was a career shift – a quite obvious necessity given the lifestyle possibilities offered by late 19th-century Siberia.

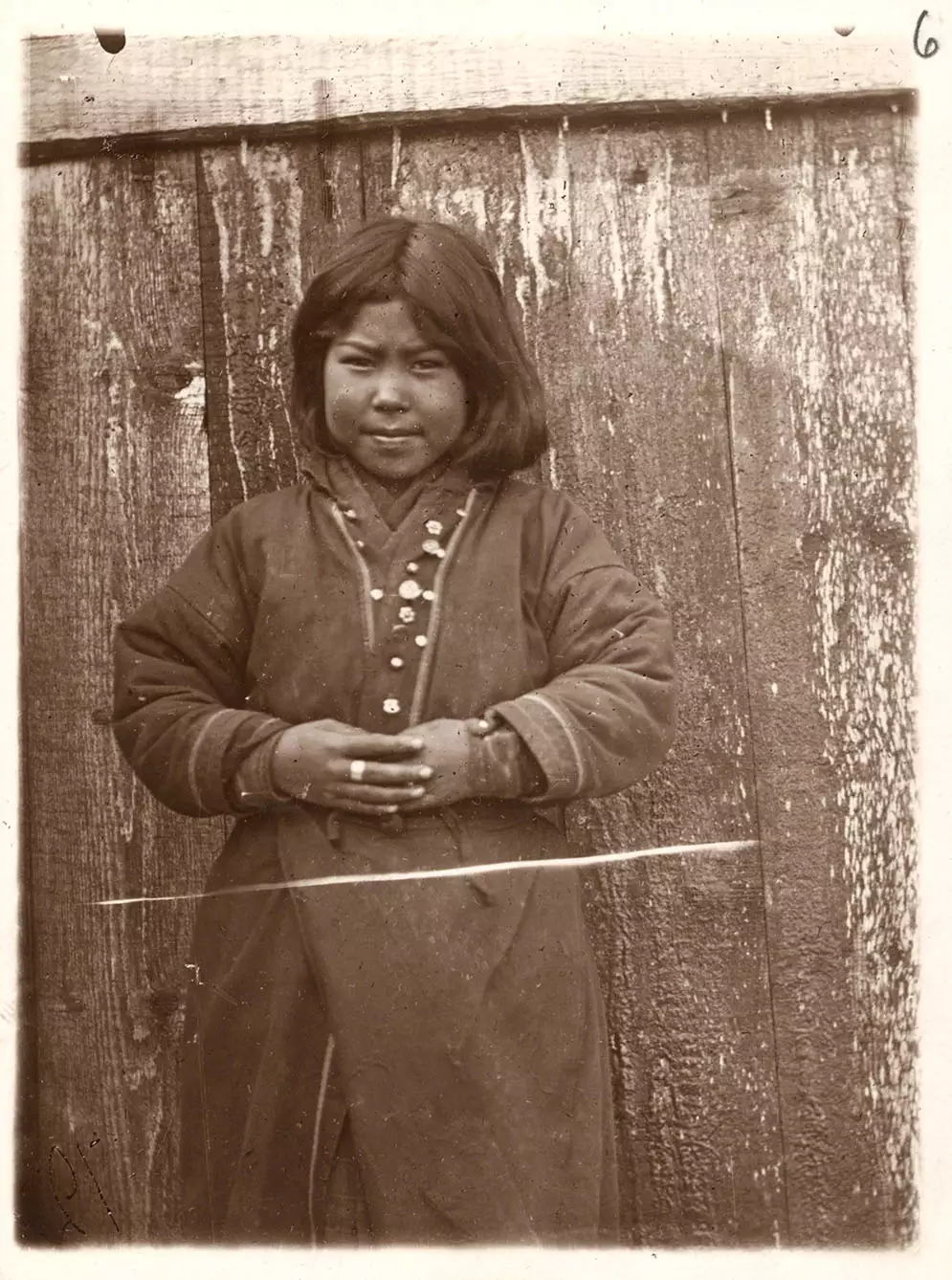

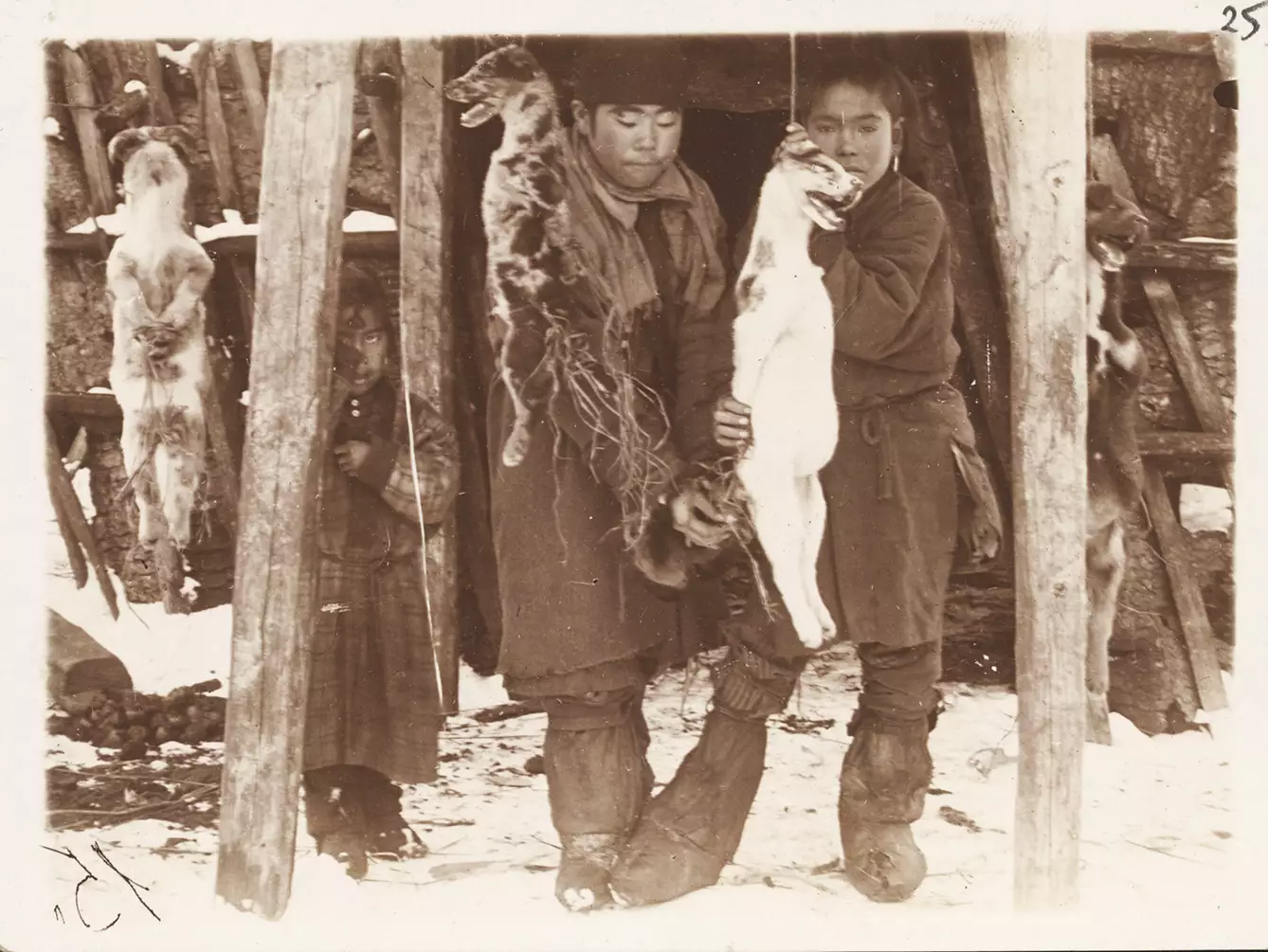

Bronisław Piłsudski became an ethnographer. Despite the lack of proper ethnological university training, he managed to secure a grant after some years from the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences. He settled among the Ainu people, where he even married and conceived two children. Piłsudski’s account of the Ainu culture is somewhat intimate.

It’s also monumental, documenting a world that no longer exists, with the last remaining native speaker dying in 1994. Bronisław Piłsudski documented the Sakhalin Ainu culture through photography and a cinematic camera. Besides the soundtrack of his videos, he used Edison wax cylinders to record the voices of the Ainu and recorded their tales in writing. He even compiled a dictionary of a few thousand Ainu words.

Ainu: the lost world

It was only in the 1980s, almost a century after the deed, that the Japanese would use laser technology to digitally remaster the content of the most important account – the Ainu language in speaking. This tribe, connected to modern Japanese people, was already extinct. Thus Piłsudski’s “tapes” are the only recorded account of this proto-Japanese language.

The later history of the scientist is a mix of threads: living in Japan (where his descendants live to this day), befriending Japanese artists, statesmen, and scientists, a brief episode in post-World War I Poland, then political activism in Paris (in favor of the party opposing his brother’s), culminating with his death in the Seine – possibly by suicide.

As many Poles of the era do, Piłsudski also has two graves – a symbolic one in Poland and an actual grave where his remains are interred in Paris. But his greatest monument is, somewhat inconspicuously, a set of wax cylinders, miraculously found decades after his death.