Bulgaria didn’t send a representative to the 2023 Eurovision Song Contest, but those in the country willing to cheer for someone with a Bulgarian last name didn’t have to look further than Poland. After all, wasn’t Blanka Stajkow, the 24-year-old singer representing Poland, also representing Bulgaria through her Bulgarian-born father? It sounds like a stretch, but make no mistake: Polish-Bulgarian cultural ties can’t be overlooked. And decades in the making, they’re still going strong.

Connected through film

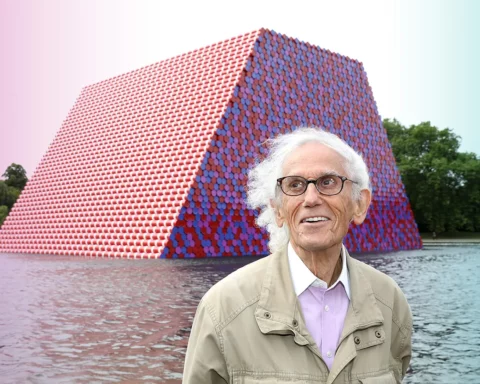

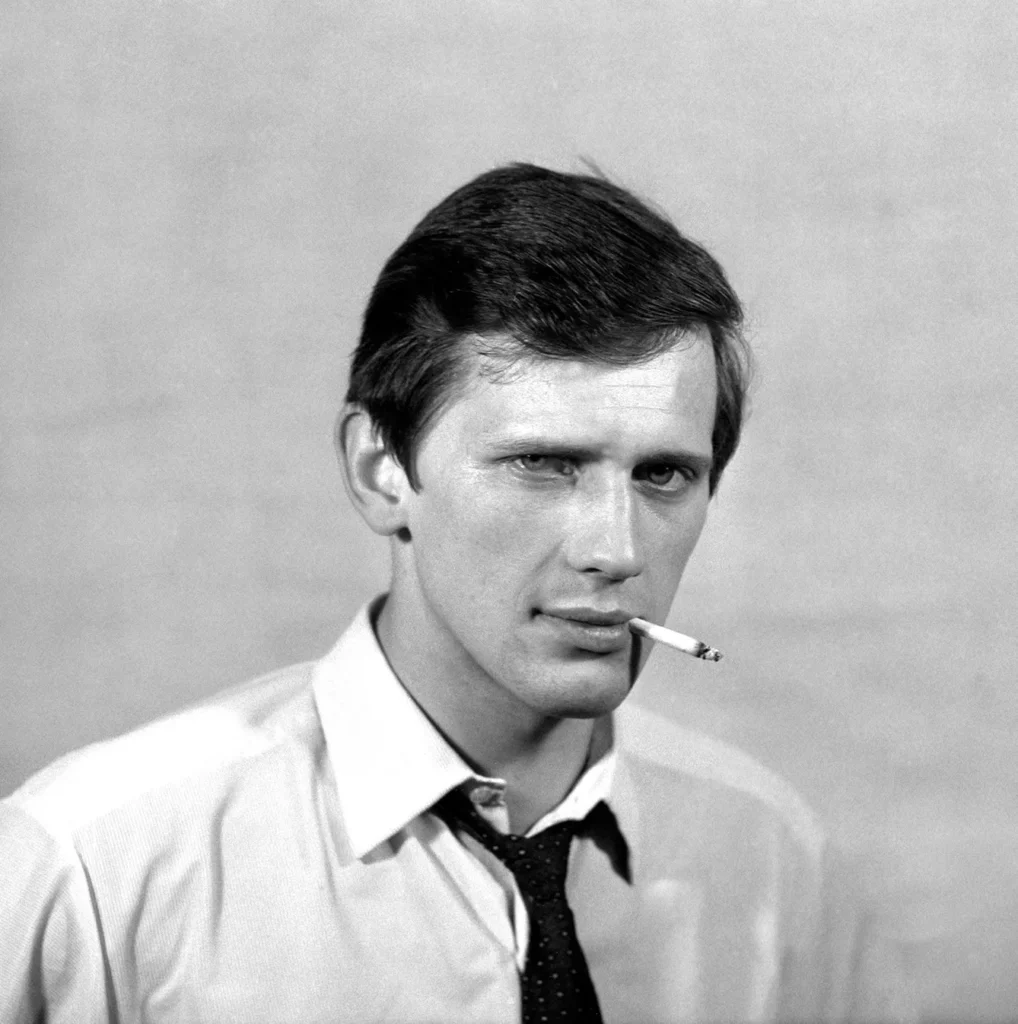

Almost 50 years ago, a young Polish actor made a name for himself in Bulgaria by starring in “Doomed Souls,” to this day a film with cult status in the country. Auditioning for the leading role of Heredia, the Jesuit priest, against none other than Egyptian superstar Omar Sharif, Polish actor Jan Englert, today Director of the National Theater in Warsaw, became a star in Bulgaria. But also, in his own words, he further connected the two countries, something the numerous awards and recognitions Englert has received in Bulgaria confirm. “I have played 150 roles in my life, but none reaped the success of the role of the priest, Heredia. I have received great recognition in your country, so I feel like an ambassador for Bulgaria in Poland,” Englert said in an interview.

Jan Englert was representing Poland at times when the country was considered the ultimate cinema powerhouse in Bulgaria. In the 1960-1970s, Bulgarian directors trained in the world-famous Leon Schiller Polish National Film, Television and Theatre School in Łódź, commonly known as the Łódź Film School, returned to their home country.

Bringing Poland to Bulgaria…

“Polish graduates such as Ivan Nichev, Vladislav Ikonomov, and my father, Borislav Punchev, essentially brought Poland, its cinema, and theater to Bulgaria. Bulgarians who studied in Łódź then went on the teach at the Krastyo Sarafov National Academy for Theatre and Film Arts, educating generations of Bulgarian actors and directors,” Warsaw-born producer and director Boriana Puncheva, who for close to a decade also ran the Bulgarian Culture Center in Warsaw, told 3Seas Europe.

Also, back then, Polish design was made widely available through a chain of shops in all major Bulgarian cities. Known as “the Polish Center,” these stores offered, among other things, high-quality Polish products such as textiles, clothing, porcelain, posters, and paintings. Today, with the Iron Curtain gone and movies from all over the world available on your phone, standing out in a crowded cultural space might be difficult.

…And vice versa

Lately, change has been in the opposite direction. You have seen more of Bulgaria and its culture in Poland over the last 20 years. In the years of socialism, Bulgarian culture wasn’t of much interest in Poland. This has changed through music, literature, theater, and cinema, but we still need consistency. Bulgaria lacks strategy on how to present its culture abroad in the long run,” thinks Boriana Puncheva. As nice as it is, one concert or a visit from a Bulgarian theater every few years is not likely to change much. Bulgaria needs to make a name for itself besides just being a once-beloved Black Sea destination. We need to be looking for cultural niches,” she adds. According to Puncheva, Bulgaria is attractive to Poles with its ancient history, folklore, and traditional music. Just something to think about.

In Warsaw, not far from the Bulgarian Culture Center, Yordanka Ilieva-Cygan works at the University of Warsaw’s historic campus with the next generation of Poles who will bring Bulgaria closer to Poland. A lecturer of Bulgarian language at the University of Warsaw’s Institute of Western and Southern Slavic Studies, Ilieva-Cygan is opening the doors to Bulgaria, its language, and culture to a small but dedicated group of dedicated students. “Once they start their studies, our students really integrate their interest in all things Bulgarian into their lives going forward. It becomes a job, a mission, a passion,” Yordanka Ilieva-Cygan tells 3Seas Europe.

In 2013, Ilieva-Cygan started, not without the help of her students, “Smokinia” (Fig), a magazine exploring all areas of interest in Bulgarian and Polish. Today, having migrated from paper to digital format, the magazine is offering its platform to students of other Slavic languages at the University of Warsaw too. “The interests of my students are all-encompassing, from music, cinema, and folklore to feminist movements. Over the years, the students have taken it upon themselves to promote Bulgarian culture in Poland. And that gives me hope that these bridges will continue to stand,” says Ilieva-Cygan.

Closer ties

While the Polish language is also being taught at universities in Bulgaria, and Sofia is home to a busy Polish Institute, in schools in Sofia and Varna, work starts earlier. Named after the great Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, two schools located some 440 kilometers apart, teach the Polish language and culture to their young students. “It’s a very active cultural exchange. Polish culture is obviously very close to us,” tells 3Seas Europe Vanya Mineva, Principal of the Adam Mickiewicz High School in Sofia. In Sofia, another school affiliated with the Polish embassy also teaches the Polish language and culture. In Warsaw, a similar school, only teaching Bulgaria, also operates.

In Varna, Bulgaria’s Black Sea capital, the other Adam Mickiewicz school marked a quarter century of existence in 2022. Set up as a weekend school to meet the needs of members of the Polish diaspora or children of Polish citizens temporarily residing in Bulgaria, the school, which teaches not only the Polish language and literature but also history, geography, and knowledge about society, has been seeing interest from students who have no previous relation to Poland. One of them, hailing from the town of Targovishte, 120 kilometers west of Varna, wakes up at 4 in the morning every Saturday to be at school on time.

“These Bulgarian children don’t come to our school out of obligation. They come with pleasure to learn Polish,” Polish language teacher Elżbieta Beyeva tells Bulgaria National Radio. “It’s very cool to learn Polish,” the students offer. The connection continues.