How do you turn a city into a giant gallery of art? It’s easy – just invite the artists and let them do their job. That’s exactly what happened in Elbląg, a medium-sized city in Northern Poland of just over a hundred thousand inhabitants. Although the Biennale of Spatial Forms happened there for the last time half a century ago, the project’s remnants have withstood the test of time and ornate the city to this day.

State-sponsored artists

The art market under socialism was different than what existed on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Whereas in the Western model, art is a kind of competition between artists, their representatives, galleries, and buyers, there are models for the state-supported art market. The socialist one, modeled in the countries of the Eastern bloc, was connected to cultural institutions.

Obviously, the downsides are probably what first comes to mind. For example, how easy it would be to mute the voice of art in several easy steps. Like selling paper to printers for only “appropriate” books. However, in both capitalism and socialism, the easiest form of suppression is money.

But money and other monetizable resources can also be an advantage – and the sheer number of notable artists that came out of socialist Poland serves as proof. (Magdalena Abakanowicz‘s recent exhibition at the Tate Modern in London is one.) The state muted dissident voices but, for most of its history, was not strongly opposed to the pure form in art or the reflection of the human condition in general.

Sculpting the machines

Now that we’ve gone through the general, let’s get technical. Under socialist economic rules, most of the industry was owned by the government, and there was no clear delineation between state vs. industrial sponsorship of art. Major exhibitions in museums and galleries were subject to the decisions of the Ministry of Culture and Art, but large industrial complexes also had a budget for promoting culture.

Among these industrial complexes was Zamech – the Machines Factory in Elbląg, which ran Gallery EL. Led by Gerhard Kwiatkowski, a Polish-German painter and installation artist, in 1961, he managed to get his sponsors to organize a biennale. His argument was strong: Elbląg, named Elbling until 1945, was an ex-Prussian, aka German, city, and launching a major art project sponsored by Poland was an opportunity to overwrite its German heritage with Polish history.

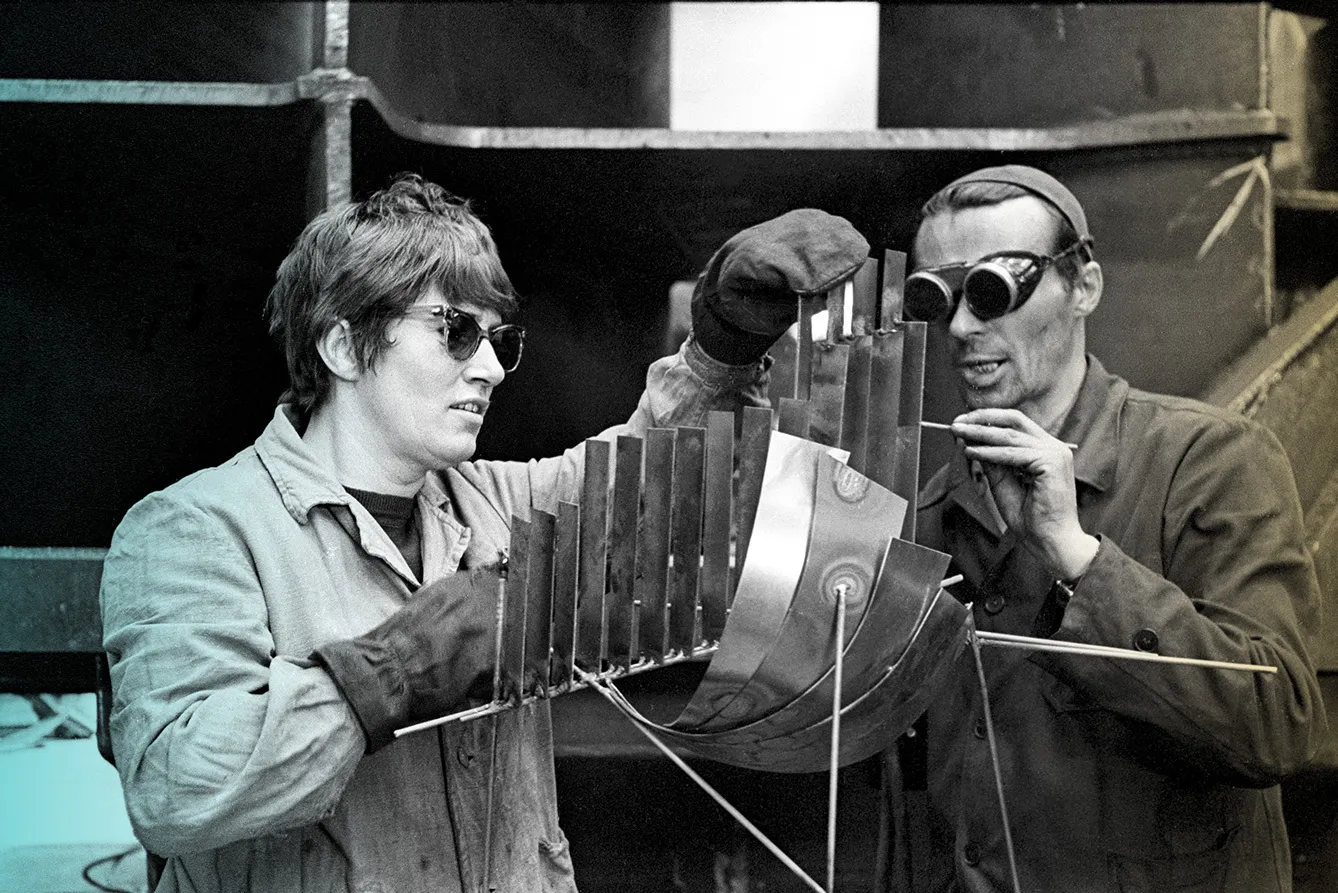

The project was named the Biennale of Spatial Forms in Elbing, and its association with Zamech Factory was strong. Its heavy industrial and factory spaces allowed notable artists to explore the concepts of space in art and gave them access to the use of the factory’s heavy equipment.

The first Biennale was organized in 1965, and the project had five iterations – until the last one in 1973. Polish mid-century art aficionados will appreciate a list of artists invited, as it was crème de la crème of Eastern Bloc form-oriented artists like Magdalena Abakanowicz, Edward Krasiński, and Jerzy Rosołowicz – just to name a few.

The art of living

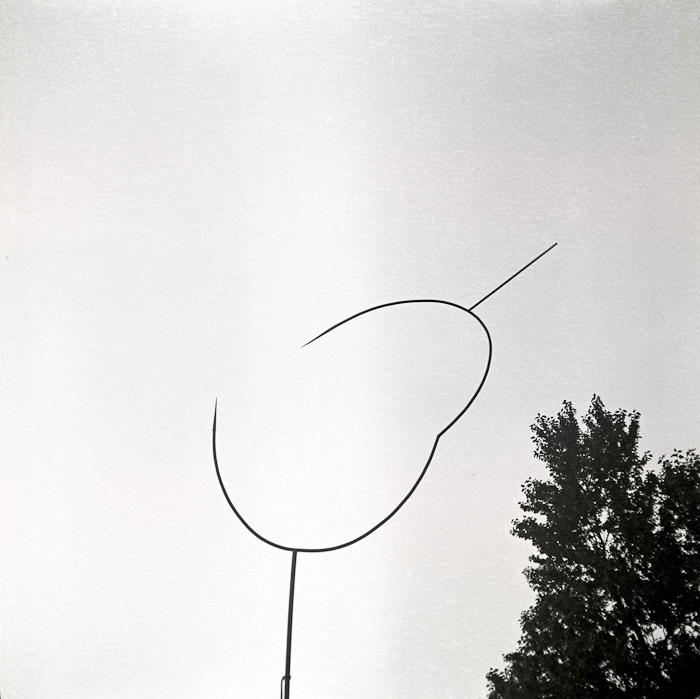

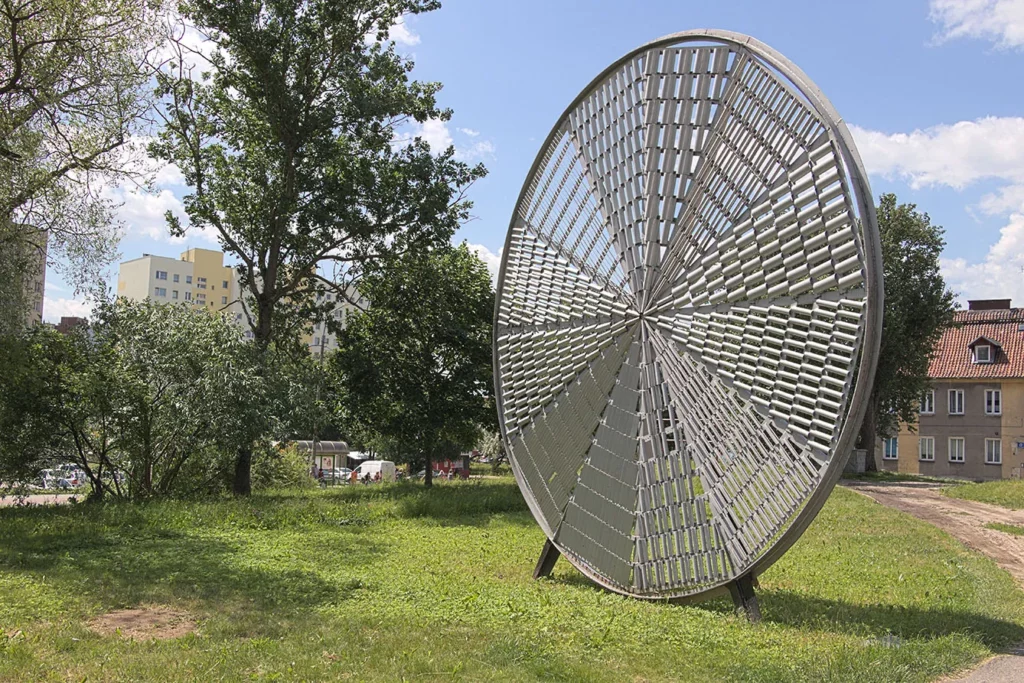

Access to professional tools and materials with a creative mix of different artistic approaches resulted in spectacular effects: mostly abstract and geometric, exploring spatial relations. Some sculptures are many meters high, and all are eye-catching.

Don’t believe it? It’s easy to see for yourself, as there was also one condition for the artists – the results of their work were to be exhibited in the city’s public space that hosted the event. And, as a shining example of the robust products of the factory, there they stand to this day.

Elbląg is peppered with works whose significance and meaning are perhaps incognito to average pedestrians but are lauded by the modern art world. In the 2000s, the art is still appreciated – and hidden meanings of the forms are still being explored, like in a 2012 conference held by Karolina Breguła that examined how the artworks have ingrained themselves into the city’s fibers and into the inhabitants’ consciousness.

Public parks and squares are adorned by this unusual urban furniture, making Elbląg a perfect spot to live among art.