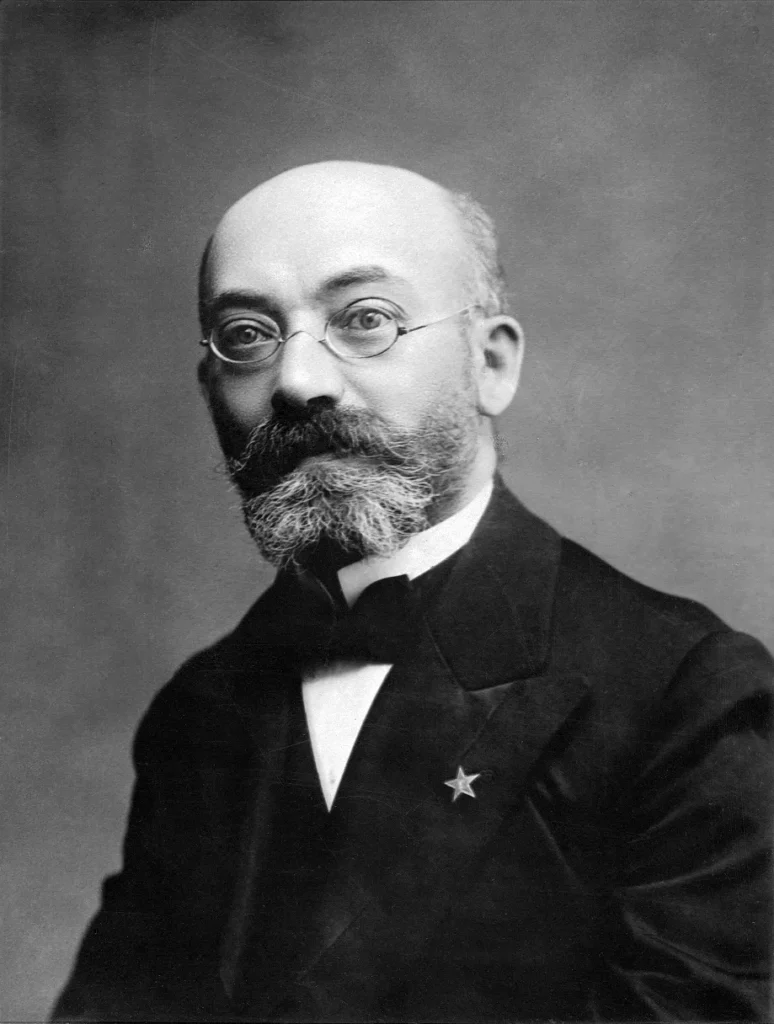

Born in 1859 in Białystok into a Jewish family, Ludwik Lejzer (Lazarus) Zamenhof knew what living in a community prone to misunderstandings meant. Speaking Yiddish at home, he lived in an area where Poles, Russians, and Germans were also present (not to mention some of them would use the other languages as their second tongue). This led Ludwik to believe that languages were the source of all misunderstandings. Aged only ten, he wrote a drama entitled “The Tower of Babel – a Tragedy of Białystok in Five Acts,” expressing his then-formed belief that a common language would end all human misunderstandings.

His family moved to Warsaw, where, in 1878, he turned his belief into actions by forming an early version of what he called the Lingwe Uniwersala. Despite not pursuing a career in linguistics and turning to ophthalmology, Ludwik continued to work on his universal language idea. He based his new language on solid fundaments of known national languages, and finally, in 1885, his product was ready.

It took a further two years to find a publisher who would print the handbook Zamenhof had written, but finally, on July 26, 1887, his book Unua Libro found its way to bookshelves. He published his work under a nome-de-plume – Doctor Esperanto (the doctor, who hopes), which should give you a pretty good indication of the language we are talking about here.

Esperanto – a language with a mission

The original name of Lingwe Uniwersala did not stick. Instead, the new language was named Esperanto, after the nickname Zamenhof chose to publish his work under. The name was fitting as, indeed, the first students and speakers of Esperanto had high hopes to change the world with this incredible gift. Indeed, this was partly thanks to the fact that Esperanto was not just about the language. It became a new philosophy of life. (*If you have time, we suggest checking out the idea promoted by Zamenhof – Homaranismo. A philosophy that its Goldern Rule can summarize: Treat others how you want others to treat you.)

The motivation was to try to introduce a new quality of relationships between people. Zamenhof was a nine-time nominee for the Nobel Peace Award for his development of Esperanto and his fight for global peace, though he was never awarded the prize.

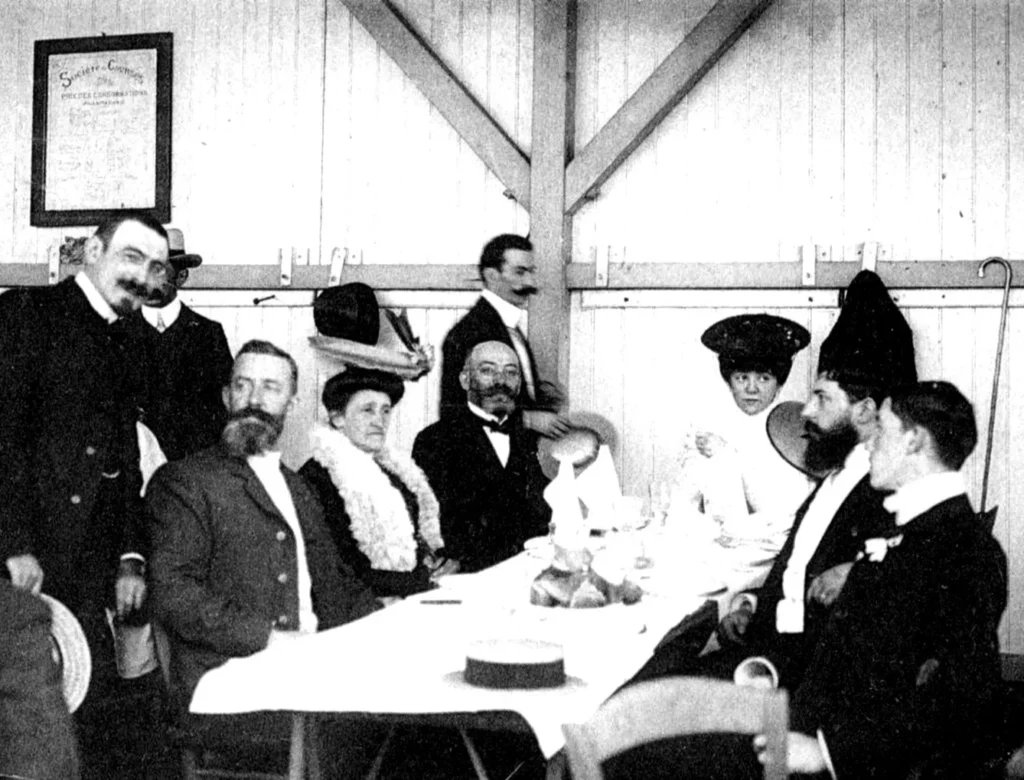

Esperanto took the world by storm. Leo Tolstoy is said to have claimed that, “Every minute invested in learning [Esperanto] will reward you a hundredfold.” In fact, Esperanto was spoken by many influential people of the 19th century, such as Tonkin Soros (father of George Soros), who wrote his shocking account of the German extermination of Jews in Hungary during the Second World War in Esperanto. His son also speaks Esperanto as his first language, and, in fact, the surname ‘Soros’ is an Esperanto word meaning ‘shall soar.’

Ludwik Zamenhof’s influence

Joseph Tito was another historically known figure who spoke Esperanto, as was Franz Jonas, the President of Austria (in office 1965-1974), and another president of this country, Heinz Fisher (in office 2004-2016). Many intellectualists, writers, linguists, and poets, past and present, learned Esperanto. Let us mention, apart from Tolstoy, Julian Tuwin (influential Polish poet), Louis Jean Lumière (the French inventor of cinema), László Polgár (renowned Hungarian chess teacher), and no other but J.R.R. Tolkien. The latter Esperanto researcher was trying to distance himself from the movement in later life due to personal beliefs that language cannot be separated from a myth. However, he did advise “all who have the time or inclination to concern themselves with the international language movement would be: ‘Back Esperanto loyally.'”

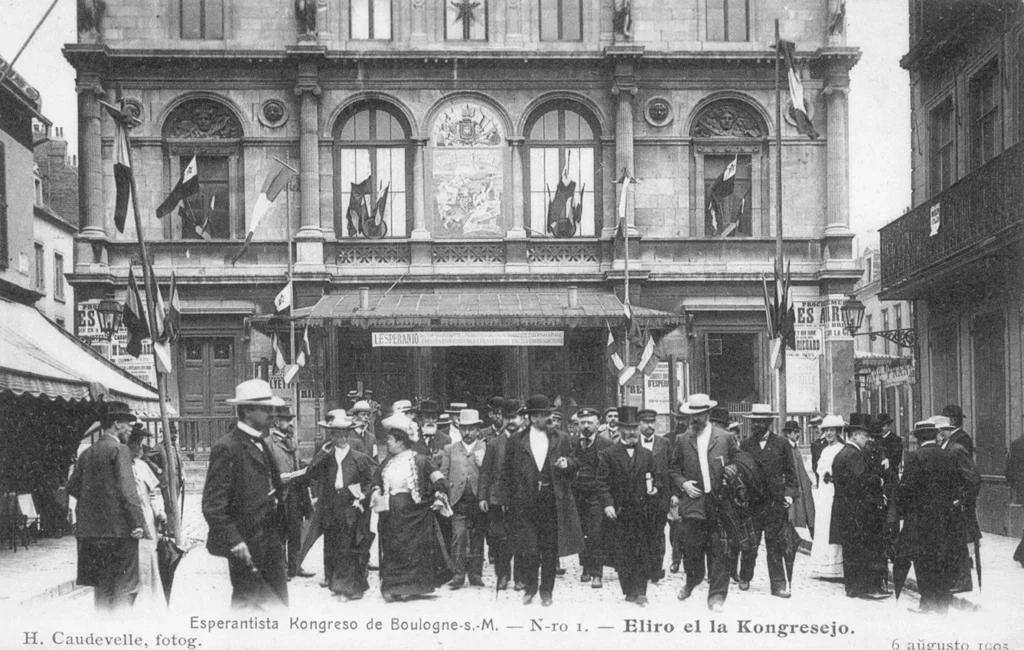

Globally spoken

Approximately 1.5 million people speak Esperanto in the world. The movement of Esperantists is strong globally, with its important centers, apart from Poland, based in the UK and the USA. It is recognized by linguists and offered as a module at universities as well on official certification courses.

Esperanto was proposed as the UN working language in the 1920s, but the motion did not succeed. Its speakers are still, however, actively trying to make it more widely recognized. It is, in fact, one of the official languages of the liturgy of the Catholic Church. There is also a film starring William Shatner, Incubus, which was filmed in Esperanto. Esperanto is the most widely spoken, constructed language in the world, with a healthy number of native speakers called Deskanuloj. And it is impressive to think that the Polish epic poem, Pan Tadeusz, kept its Polish Alexandrine form in only one translation: into Esperanto. Lastly, Esperanto was entered on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Esperanto started as a way to change the world. Despite not gaining global recognition at the level it aspires to, it is still spoken more widely than Elvish. Perhaps then, there is still a chance it will become the lingua franca Zamenhof dreamed it up to be. After all – it promotes hope, unity, and respect. Values allegedly shared by the entire humanity.