The bison is one of the oldest species living on Earth. The species lived alongside mammoths, woolly rhinoceros, and saber-tooth tigers (yup, that long ago). It originated in today’s Asia, and since it was incredibly large (about 2 meters tall and 3 meters long – about a size of a lorry), the bison migrated to settle happily on the continents of North America and Europe. Cave drawings of bison were a common feature of prehistoric wall art, which testifies to the wide presence of the species as well as its importance to humans.

Reaching the tipping point…

In the 18th century, the population of wisent (another name for the European Bison) declined, and it was only possible to come across herds in Central Europe and in the Caucasus Mountains. The only reason the species made it that long was through the early conservation efforts by the Poles. The wisent became a protected species by a decree of Sigismund the Old, who forbade hunting the animal in the Lithuanian forests from 1529.

In 1795 the bison population in Puszcza Białowieska [Białowieża Forest] amounted to about 700 animals, but although this part of Poland fell under Russian rule during the partitions, Tsar Aleksander I kept the protection of the species in force. A record-breaking population of European bison was recorded in that area in 1857 (1898 animals). However, difficulty with finding suitable feeding grounds and war conflicts led to a steady decline of the wisent.

… and falling over

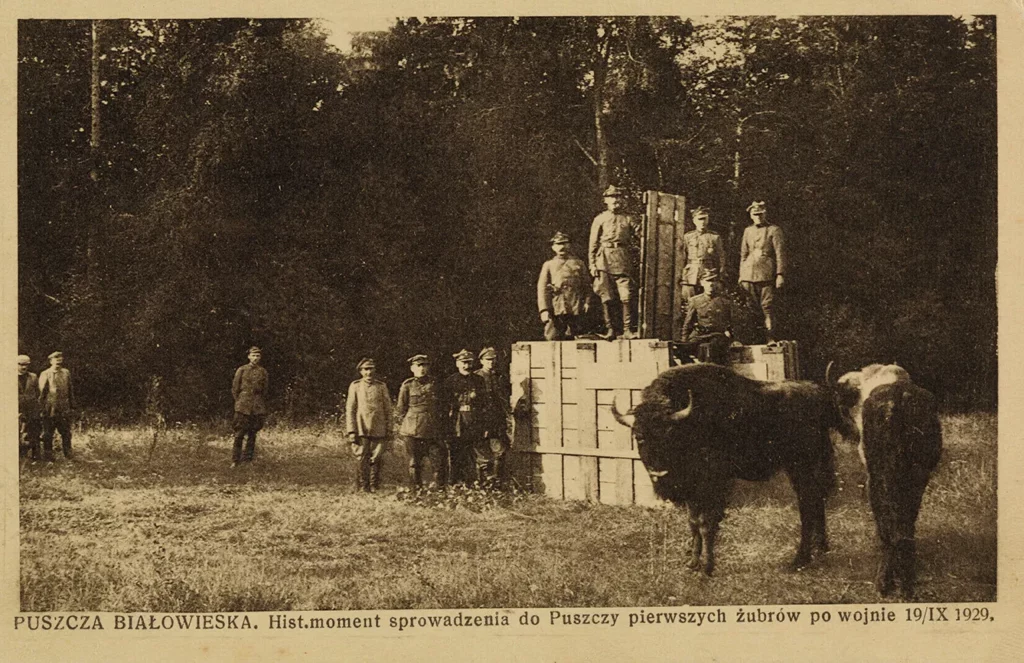

The last free bison in Poland was found in 1919 – soon after the end of the First World War. Some seven years later, the Caucasian population shared the fate of the Polish herds. With no bison in its native forests, there were only two options: mourn the species or act, and act fast. Thankfully, Poles chose the second option. They realized that although the free population was extinct, a dozen or so animals were still living in European zoos, where they were shipped as gifts between the 19th and 20th centuries. At the International Summit for Environmental Protection of 1923 in Paris, a Polish delegate, Jan Sztolcman, presented Poland’s plan for saving the European bison. That same year, the Society for the Protection of European Bison was established.

Pedigree breed

Because there were only 54 bison with traceable origins alive in the world, it was necessary to record the purity of the breed. The first European Bison Pedigree Book was published in 1932 in Germany. Doctor Jan Żabiński, the famous director of the Warsaw Zoo who saved Jewish children during the war, became the main editor of the Pedigree Book after the war ended. From 1947 onwards, the publication was prepared and printed in Poland.

Apart from all the diplomatic work, Poland was also actively trying to breed bison for the purpose of reintroduction. In 1939, Poland’s population of wisent grew from 0 to 37 animals, out of about 115 in total alive globally in the wild. After the war, the world population decreased to 103 wild wisents, while Poland’s population grew to 44.

First reintroductions

The first two bulls were released into the wild on 13 September 1952. The first female and her calf joined the two older bulls a year later. Although the beginnings were rough, the animals adapted well to living in the wild, showing that the scientists were leading the project in the right direction. Thirty-eight animals were released between the years 1952 and 1966. Reintroductions stopped as of 1967, and everyone held their breath. Thankfully, the plan worked! In 1971 there were 211 European bison living in the Białowieża Forest. And the population continued to grow.

A record-breaking herd

It is estimated that as of 31 December 2021, there were 2492 wisents living in Poland (206 in captivity). This is the largest wild population of European bison in the world. It shouldn’t, therefore, come as a big surprise that European bison herds living in Poland can be rather numerous. Still, the scientists were pretty shocked when in December 2022, their drone registered a herd of… 170 animals (40 of which were calves)!

Such super-herds are unheard of and were probably created as a result of a few smaller herds joining together. Still, it is heartwarming evidence of what can be achieved in the field of the preservation of the species. We have generations of Polish scholars to thank for their enormous efforts to save the wisent. They succeeded even though it was a long shot.

Poland’s example should also serve as a reminder that most such stories do not have such happy endings, and if we are so glad to have saved one of the world’s species, perhaps we should think twice before we go and destroy another ten of them.