Although Warsaw is the capital of Poland and is now metonymous for the country as a political actor, for centuries, the southern city of Kraków was the most notable center of Polish culture. The stunningly large medieval town here was developed around the needs of rich merchants and was presided over by a magnificent royal castle perched atop Wawel Hill.

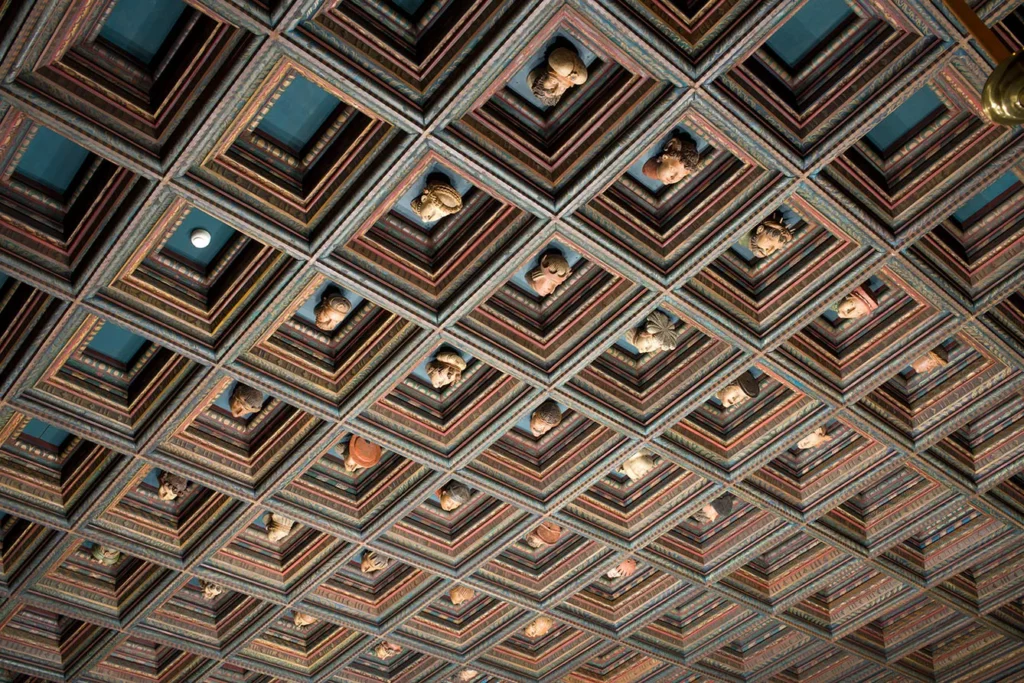

Even the hill itself is legendary, known for a cave supposedly inhabited by the Wawel dragon. However, it’s the Renaissance castle on top that draws the most attention. Every chamber is magnificent and unique, and the Representatives’ Room is one of the most famous. Just look – or be looked at from – the ceiling.

The coffered ceiling of Wawel castle

The Renaissance came to Poland from Italy thanks to Bona Sforza, who became the queen of the country. As it swept across the country, it brought along several trends, like eating vegetables. And thanks to the royalty who introduce it, the Renaissance influence retained its regal manner, rich and pure as Italy was imported, not just the style. The coffered ceiling of the Representatives’ Room in Wawel is an illustration of the idea.

In 1540 or thereabouts, two woodcarvers, whom we know mostly by their names (German names, which was not unusual in Kraków at the time), were commissioned to make a ceiling. But with the usual floral or abstract design of the coffers, the whole construction was ornamented with heads.

But whose heads were they? The problem (well, maybe not as much as a problem, but rather a curiosity) is the interpretation of the ceiling. The heads are a riddle, indeed. One thing we know is that they represent people of different social statuses, occupations, and perhaps even ethnicities. Such diversity can be impressive in that, originally, almost two hundred of them were created and mounted onto the ceiling.

A Who’s Who of Wawel heads

But the faces are also strikingly diverse in terms of facial expressions and features, leading to the conclusion that they were modeled after particular people. Who were the models? Perhaps just regular people, though some researchers point to certain faces resembling famous people, including king and future Western Roman Emperor Ferdinand I Habsburg.

This only adds one more question mark to the general issue of the ceiling’s interpretation. Was it all about the social cohesion of the kingdom, or did it represent some history? Or perhaps – as some other art historians point out, was the whole ceiling a religious or astrological narrative?

[smartslider3 slider=”18″]

We will never know, especially since the intended design never materialized. Soon after the coffers were ordered, a Wawel Castle fire destroyed part of the chamber, and the rebuilding effort led to some concessions. The heads were installed in an easier and cheaper way, one next to each other.

It’s worth adding that when examined up close, individually, the heads are not really precious pieces of art. It’s when you take them in together that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. They were never intended as individual works. That’s perhaps understandable when you take into account that, as one historian counted, the craftsman, Tauerbach, was paid only 24 grosz per head, which is equivalent to around USD 120 today – not really a true artist’s fee.

The 20th-century expansion

The heads on the ceiling, unmaintained, remained in their place until the eighteenth century. After Poland was divided into hostile empires that were not interested in sustaining Polish culture – the precious monument on Wawel Hill was turned into Austrian barracks, and the 250-year-old woodwork was almost destroyed. Out of 194 original heads, 30 remained. Famous Polish culture conservationist of the time, Princess Izabela Czartoryska, took them to her sanctuary in Puławy. However, after the 19th-century political turmoil, the collection was dispersed, with some of the heads ending up in Moscow.

When Poland was reborn after World War One, all thirty returned to Wawel and were put in their place again. But the collection was expanded – in the mid-twenties, Polish sculptor Xawery Dunikowski expanded the collection by sculpting twelve famous figures, including royalties of the bygone era, and artists such as Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz. The expansion is to be found – not in the reconstructed ceiling, but still in the Wawel Castle’s collection.

Dunikowski, apparently, had some idea of the heads’ meaning – or at least what the meaning was supposed to be. We don’t – but feel free to take a look and try to make some sense of them on your own.