The stereotypical, three-tier feudal society in the 16th through to the 18th centuries in Poland-Lithuania Commonwealth was not inclusive of all states and ways of life. Among the excluded were Jews – not peasants and not granted full civil rights, distinctive at first sight and maintaining their otherness.

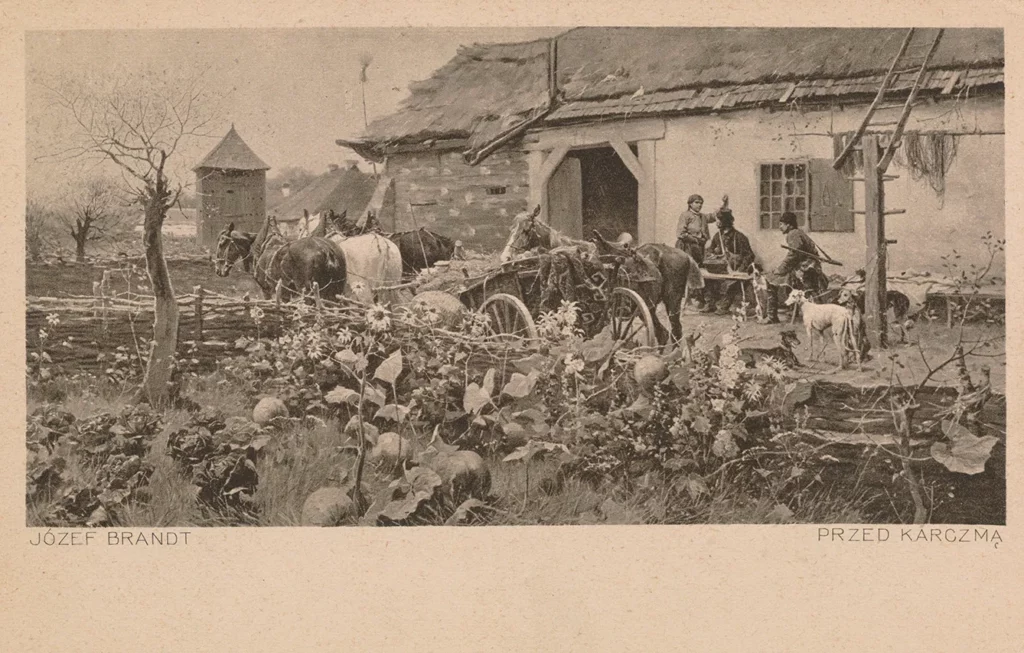

Their special status translated to the economy: their fate connected them to noble landowners by the idea of a lease, called an arenda – the Jews would lease and operate facilities such as mills or distilleries. And an arenda was also central to the idea of a tavern (karczma). Let’s take a deeper look into tavern’s functioning in Central European early modern society. The tavern was crucial to how society functioned in Early Modern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, beyond your usual pub.

From a pub, to a tavern, to a coffee house

On second thought, why actually not? After all, a pub is short for a public house, the kind of multi-purpose venue for leading a social life. Before the arrival of a coffee house (and in the 19th century modern societies, coffee houses were places to make politics), the pubs were spaces to discuss politics and social affairs, to meet and organize, to hold voting or any other kind of decision-making.

They also served as something similar to post offices (and the word ‘post’ comes from the fact that to run communication smoothly, you had to have a place to stop to change horses). There, you were able to leave a package on poste restante, trade things, and meet to finalize a deal – basically, you may see it as a convenience store for necessities. Could there be more?

Yes, there could be, and that’s where things get interesting. The tavern in Poland-Lithuania was not only a tool for running a somewhat-working country on a vast space of a million kilometers square. It was also kind of an IRS, or tax office – a somewhat oppressive one. The ambiguous role of the Jewish lessee (arendarz) was fully highlighted here.

The center of feudal life

The tavern was central to the feudal economy of Poland-Lithuania in many ways. It was an important node in the commercial network. First, there was a manor. Again, contrary to the popular image of a nobleman, they were village-dwellers of a particular lifestyle – palace-living, engaged in politics and, being a significant minority in the population, running their manors as a resource center – especially food–processing.

The manor foodscape remains strong in Poland, with different brands of meat, bread, preserves, and spirits seeking their heritage in feudal nostalgia. Manors tended to have their own distilleries, smokehouses, room to mature cheese, and other similar facilities.

The feudal system was harsh on peasants who lacked protection from the law and were forced to grant free fieldwork to their lord just because the system said so. Said peasants were providers of raw produce to process in the manor. And the produce was sold – you guessed it, in the tavern.

But wait, why didn’t peasants try to escape their lord and seek luck somewhere else? They did – and the gradual introduction of still harsher anti-immigratory laws serves as evidence of these escapes. There was one problem, though. One thing is to avoid being literally shackled, and the other one is to have somewhere to go. To achieve that, you usually needed money – after all, you couldn’t just take bags of grain to trade when you were running away from your master.

Keeping the peasants in check

Ah yes, the money. If you take a look at the system here, the money was – from the perspective of nobility – the difficult part. You had to sell your goods to have money – to pay for your child’s education, for instance, but on the other hand, you needed to keep the peasants in shape, preventing them from accumulating their own wealth. That was the basic premise of the quasi-taxation system, called propinacja (propination laws).

This unique law, especially in the early Poland-Lithuania, forced the peasants to buy a certain quantity of vodka from their landlord and him alone, in this way returning him his money in case his peasants managed to save some. Vodka was the best commodity for this purpose. It’s the most processed form of grain – therefore, the margin is the highest. It’s easily storable and transportable, so you can freely allocate quantities for internal and external trade. And it’s multi-purpose as not only a drink but a basis for some household works and a basis for tinctures.

Of course, there was another problem connected with propination laws – it (sometimes) established monopoly and minimal quantities of spirits bought. This led to the spread of alcoholism, as spirits are generally addictive.

And thus, the role of the tavern in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the role of Jews in running taverns, led to social tensions. Not forced into the peasantry, Jews were considered free and clearly business partners to the nobility. At the same time, they served the system where peasants were forced into propination laws. And when their life was no rose garden either, the accusations of exploitation were being raised.

Debunked stereotypes

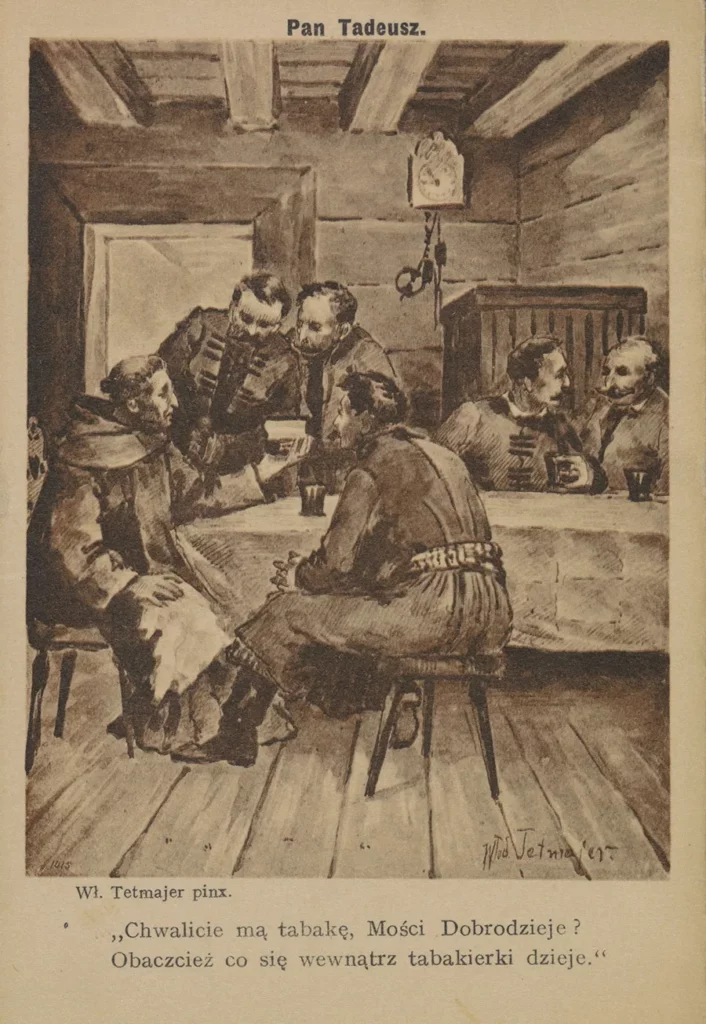

That said, there was far more to it than the anti-Semitic stereotype. The most important text in Polish romantic literature, Adam Mickiewicz’s epic Pan Tadeusz (1834), depicts all the aspects of bygone Polish-Lithuanian rural life, including the Jewish tavernkeeper.

To quote American historian of Polish Jewry Glenn Dynner, Yankel, as he was called, and his tavern are there:

[N]ot only a natural part of the landscape, they are a unifying force in fractious post-partition Poland-Lithuania. As Lord (Pan) Tadeusz and company enter the older tavern after church services, they find peasants, wives, gentry, and a priest drinking and chatting harmoniously under Yankel’s auspices. Yankel, for his part, seems to unite all of Polish Jewry in his person—sage rabbi, shrewd business advisor, just mediator, melancholy singer, rapt dancer, and, of course, tavernkeeper. He is also, implicitly, everything that Polish Jewry is not (yet). He speaks Polish with good pronunciation, is “a loyal Pole by reputation” who embraces the cause of independence, and is even an honest tavernkeeper: “Neither peasants nor gentlemen ever complained; why complain?/ He had good, choice drinks/ kept his accounts strictly and without any trickery.”

Noble nostalgia? Perhaps. But then again, with centuries of the presence of Jewish tavernkeepers deeply rooted in Polish culture, things are surely complicated far beyond stereotype.