As the 1960s approached, the communist leaders of Poland had more than a few reasons for concern. One of them was an imminent shortage in basic social services: the baby boom was coming, and there were not enough dwellings, schools, or hospitals. The cold war was at its peak, so social investments had to compete for resources against a defense budget facing an ever-present nuclear threat.

And Socialist Poland’s archenemy – the Catholic Church – was about to celebrate its everlasting presence in Poland by commemorating the thousandth anniversary of “the baptism of Poland” (which was the baptism of Prince Mieszko I and the factual beginning of Christianity introduction in current Polish lands).

Now – a budget is not made from rubber, so you need smart solutions. Is there a Swiss army knife for all these problems? There is – there was. The schools. But not just any schools.

The Polish Millennium

Staying true to the zeitgeist, let’s solve the propaganda issue first. Was the Church about to claim a thousand-year presence in Poland? Yes. So let’s give it a counter-narrative. After all, the baptism of the first ruler of Poland is kind of the beginning of Poland itself, of sorts.

Hence, when the Polish Church is having its anniversary, the atheist state will have its own birthday: the Millennial Anniversary of the Polish State. This invented anniversary was a smart solution in an effort to dim the Church’s celebration. As such, it justified the expense of organizing an event on such a scale. But it didn’t solve the basic problem of resources: where to get money from to highlight the counter-Christian narrative?

The money was needed elsewhere. Poland was expanding. It was entering the postwar era with only some 23 million people; its material base was depleted; many cities were ruined by bombing; and all the country’s borders were drawn elsewhere to where they used to be. Some emptied ex-German cities in the West, the population “repatriated” from the former-Polish territories of current western Lithuania and Ukraine. Kind of a demographic mess.

But by the time the sixties arrived, the trend was the other way around: by the early 1950s, the death rate visibly dropped, and the birth rate was at its highest in recorded history: almost 800 thousand newborns every year until 1958. By the Millenial Anniversary year of 1966, the youngest of them was already in their school age, and the main idea of a socialist country was to grant every child some education. Schools were needed, and they were needed fast.

An anniversary present to remember

This is the genesis of the idea: dress the school-building effort as the monument commemorating the Millenium of the Polish State. Clever idea, as the monument was supposed to be both visible and something to be grateful for. After all, you don’t have to align to the state narrative of the Thousand Year Country (which, it’s fair to note, evoked the still recent German idea of the Thousand Year Reich) to appreciate a modern school built for your child as a form of celebrating its supposed significance.

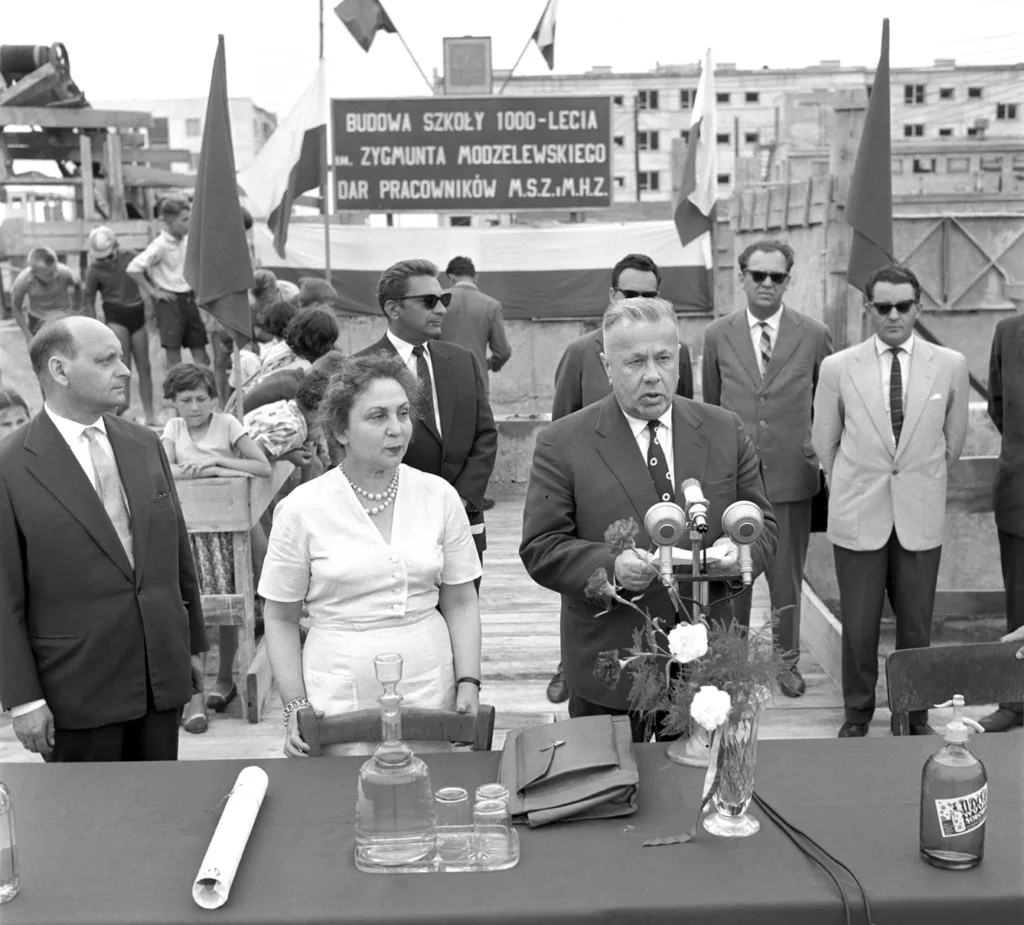

The official slogan of building “A thousand schools for a thousand years” was coined in 1958 by Władysław Gomułka, the General Secretary of the Polish communist party, and the first schools soon began to appear. The first idea was “quick and dirty” – the needs were huge, and the resources were limited. But soon, the “typical project” for the schools appeared as a two or three-story building that remains characteristic in the Polish cityscape.

Modernist, grey, with a flat roof and large windows of specific design, allowing lots of light in classrooms and ease of ventilation. The schools were built with prefabricated concrete elements and cement brick. They were modern, equipped with high-quality gyms, modern offices, and large corridors. Glass brick walls are also an eye-catching element of marrying practicality and aesthetics – this school-building effort as such became the school of the building art for the designers.

More than a thousand schools

The project exceeded expectations: overall, almost 1500 schools of the new type were built in the sixties, satisfying the needs. Most of the buildings were created based on the standard blueprint, and to this day, they are similar. But why the design?

Let us go back to the third signaled need of 1960s Poland: military security with the nuclear threat in mind. As the whole Warsaw Pact was preparing for the imminent, as it seemed, confrontation with the rotten capitalist West, the Millenium Schools had their role to play there.

The buildings, as they usually were built, could easily be transformed into civil defense objects, especially makeshift hospitals. As thousands of students in Poland, including today’s ones, easily remember, the corridors were always wide, the free space large and light, and the doorways accessible. At the ends of the corridors were science classrooms with modern equipment – including access to oxygen and gas. Everything was used in school practice, in science experiments – but could as well quickly turn large classrooms into surgeon wards.

The education for defense classes was also well equipped, sometimes with separate storage rooms. Add to that increased accessibility, shelter-ready basements used daily as students’ cloakrooms and school broadcasting centers – fun yet practical, just in case.

With all these solutions, the school buildings were just as the school absolvents are supposed to be – resilient to change and ready for the challenges yet unknown but still ahead. Modernized, altered, extended, and sometimes repurposed, the Millennium Schools remain one of the socialist monuments no one dares to touch despite the desire to reassess Central European modern history.